Our best students being unemployable – Luke Wood

11:00am, 13.08.2012

img#1

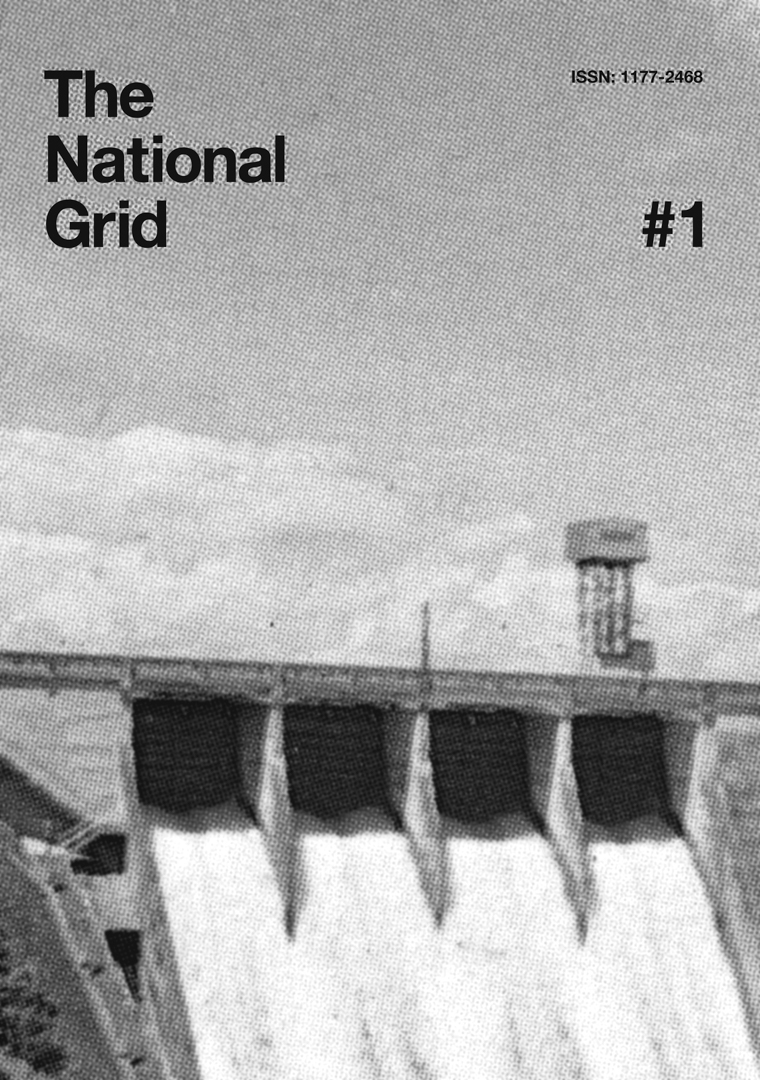

In my day job as an academic—a Lecturer in Graphic Design at the University of Canterbury’s School of Fine Arts—I am often required to present and frame The National Grid as a research project.

I’ve talked about The National Grid a number of times over the last few years, but today I want to use it to illustrate something of my, at times, problematic relationship with the term ‘research’. I want use this talk as an opportuntiy to consider what research means in an academic context, and also in the context of professional practice. Or in ‘the industry’ as they say.

img#2

Academic Practice < > Professional Practice

At times I feel I’ve become quite lost some- where in between these two worlds. And, at times, I feel like my students have too.

img#3

...we’ve often joked around about our best students being unemployable.

And this is where I want to start. With my students, and with some lurking sense of anxiety.

This is something I wrote in an editorial of sorts that we published in the very first issue of The National Grid. I’d like to address this, firstly, because I think it might illuminate something about my struggle to come to terms with what research means to me, but from the opposite direction. And then secondly because it’s been on my mind a bit since we published that first issue. If not because now and then some of my students have inevitably come across it, then because I’ve been seeing some truth to it as each years new graduates move out into the world.

Here it is with a little more context.

img#4

This whole endeavor really, is the result of us being at a bit of a loose-end. Neither of us were very good at being real graphic designers, I mean we could ‘design’ ok, but all that other stuff; time, money, people skills? Why we both ended up in education I guess. But we’re not entirely happy there either, and we’ve often joked around about our best students being unemployable.

You can see that it highlights my not being entirely happy in professional practice or in academia, and, interestingly enough, it still rings quite true.

But what exactly do I mean when I say my best students are unemployable? Is it because I don’t teach them well enough? It could be read that way, but that’s not what I mean. Actually what I mean is the exact opposite.

Without sounding too arrogant I hope, I want to say that, often times, I feel I am over-educating my students. And by this I mean that I feel I am setting up in them expectations for and about the discipline that exceed the wants and needs of the industry that these students are supposedly aiming at working in.

Am I implying that ‘the industry’ or that professional practice lacks some sort of intelligence? Yes, in way, this is exactly what I am saying. I am of course generalizing to some extent, but, that said, I will go further and say that I think the professional practice of graphic design, especially here in New Zealand, lacks literacy, criticality, and ambition.

This is a bold and possibly contentious statement. Although perhaps it is also entirely self-evident and plainly obvious? Whatever the case, my perspective is one that comes from fifteen years of personal experience working in and around the design industry in this country. It was precisely this experience that drove me back into academia, and it is this experience that now largely motivates and colours my work as a teacher.

img#5

Disenchantment > > > ““Research””

Disenchanted with professional practice and with the industry in general, I was, in part, attracted to academia by this word ‘research’. To someone who’d been working 12 hour days with usually very conservative clients wanting work done within impossible deadlines and even tighter budgets, just the sound of the word ‘research’ had a promising, aspirational ring to it. Research in the studio meant taking 10 minutes to trawl through some books, magazines, or blogs, for ideas to throw at your next job. At the time I didn’t really know what research in the academic context even meant, it just sounded good—it sounded magical, and like somehow through it I might become engaged with graphic design in some much more motivated and meaningful sort of way.

And in a sense, looking back, it did work. My naivety and my belief in some kind of undefined potential did actually allow me to begin working in new ways, most importantly I began doing projects for myself, rather than waiting around for someone to bring me something interesting.

img#6

I have worked very hard over the last few years to develop my own projects—projects that I have initiated either on my own or, like Head Full of Snakes and The National Grid, with friends and collaborators. Projects like these, in which I have a far greater sense of agency and ownership, have been really important to my maintaining an interest in graphic design, and as a result I am a keen advocate for students learning to develop a self-motivated practice that extends beyond the completion of their degree.

In my mind this might set students up, especially the more ambitious ones, with a more sustainable practice when they leave. Sustainable in the sense that they won’t become bored and bitter like I did. And hopefully as a graduate’s practice develops their personal projects might feed into and off of a viable commercial practice as well.

The problems with this approach are (1) that ambitious students become more ambitious and don’t want to spend their first few years in the industry being essentially mac-operators, and then also (2) from the opposite side, many potential employers don’t want to see a portfolio full of research-laden personal projects.

img#7

Real World vs Ivory Tower

I should make it clear at this point that I have no problem at all with a tertiary education that is not primarily vocational. I am, however, as someone with a foot in both worlds still, genuinely interested in this gap or fracture that I see existing between professional practice and academia. We’re all aware of it to some extent, no matter what side of this divide we’re on, and it’s a division that gets talked about in a variety of ways—the ‘Real World’ vs the ‘Ivory Tower’.

The way I want to talk about it though, the way I’ve been thinking about it a bit lately, is through the application of the term ‘research’. Because I can’t help but wonder if we had a more united understanding of what this actually meant, would it close up this gap and make us more able to actually talk to each other?

I know I must sound like I’m more on the academic side of things here, but this isn’t actually the case either. Let me see if I can explain...

img#8

Studio day

My second full-time academic appointment was at the School of Fine Arts at Canterbury University in 2003. I came to this position from a studio in Wellington at the time, and it was predominantly my work as a professional graphic designer that had bought me to the attention of the staff in this school. My work as a designer was important, and it was made very clear to me that the school wished to support my continuing practice as a designer, as it was understood that to be a useful teacher I should also be a practitioner. Part of this support at the time was that I was allowed to take one day of every 5-day working week as a ‘studio day’.

A year or two after I was employed in this position an interesting thing happened.

img#9

Studio day > > > Research day

What we had been calling our studio day mysteriously turned into a research day. At first I had no problem at all with this. Remember I had been quite mesmerized by the word research.

So was the government in fact.

img#10

PBRF:

The primary purpose of the Performance-Based research fund (PBRF) is to ensure that excellent research in the tertiary education sector is encouraged and rewarded. This entails assessing the research performance of TEOs and then funding them on the basis of their performance.1

I had no idea at the time but just before I’d arrived at Canterbury University the New Zealand government had already initiated a major change in focus for tertiary funding. Now, instead of research funding being based on the number of students an institution had, this funding would be awarded based on the quantity and quality of the research being performed at each particular institution. This is known as the Performance-Based Research Fund. Or PBRF for short.

While this might sound perfectly sensible on one hand, the problems inherent in this process of standardized testing are complex and broad, and there has been much controversy and upheaval, not always for the good, as a result.

img#11

Problems:

(1) How quality is measured

(2) What is or is not defined as research

The problems are largely to do with; (1) how quality is measured, and; (2) what is or is not defined as research. These problems aren’t specific to graphic design, but affect a broad range of disciplines, especially those that contain components of professional practice such as nursing and even engineering. The PBRF unashamedly favours, and was really set up for scientific research and its dissemination via academic journals.

For me, as a graphic designer, problem #1—how quality is measured—is quite simple. Quality evaluation, according to the Tertiary Education Commission, who run the PBRF, is performed “by expert peer review panels”.2

Again this sounds quite logical. Who better to evaluate your work than a panel of your esteemed peers who are experts in your field? But, if I tell you that no one with any sort of real background in graphic design has ever been employed in this process for any of the funding rounds, you can begin, perhaps, to understand my frustration and the seeming absurdity of the exercise.

Why is this though? Why this total lack of representation? This, I think, might have something to do with graphic design. What it is, howitisdone,andhowitmayormaynotbea producer of knowledge. And this is all really problem #2—what is or is not defined as research.

img#12

What is research?

The systematic investigation into and study of materials and sources in order to establish facts and reach new conclusions.3

To research, in the broadest sense, means to generate knowing or knowledge. We all sort of do this everyday, and at some basic level we are all researchers.

We might use the word when we are looking into buying a new car, cooking something new and ambitious for dinner, or watching a documentary on something that is of particular interest. In each case we are engaged in a strategic process of discovering new things and, possibly, coming to new conclusions.

However the use of the term ‘research’ in everyday language is quite different from its more ambitious and strict employment in the academic world. As opposed to the individual searching through existing information that I have just described, research in the academic context is typically expected to generate genuinely new and original facts, ideas, and perspectives that lead to some overall advancement of knowledge. This can range from a small contribution to a specific discipline or field, to a more broadly significant discovery that changes the way we see the world around us. Like the theory of relativity for example.

And that’s the real goal. That’s what the university, and not incidentally, the government, would like to see—world changing discoveries. Big discoveries that bring in big dollars.

Universities are quickly shaping their public image around these sorts of aspirations, and you’ll see no end of TV advertisements and billboards proclaiming that if you go to this, that, or the other university you will undoubtably be an integral participant in some world changing activity.

img#13

So the question is how do I, as a humble graphic designer (and very much not a scientist), engage in this sort of process and work towards these kinds of ends?

For me it’s really important to remember what graphic design is. Jonty is going to address this more specifically in is talk, but for now can we at least agree that it exists first and foremost as a form of practice—a way doing something. It is, then, knowledge of this way of doing something that any research should, I think, ultimately contribute to.

So coming back down to Earth, the question— what is research?—might now be more usefully reframed as: how does research engage with and contribute to practice?

img#14

Research

FOR / ABOUT / THROUGH design

I have found it useful to consider the engagement of research with practice in three more-or-less distinct ways—research for design, research about design, and research through design. This is a fairly broadly accepted model, one I was introduced to in a ‘Research Methods’ paper during my own postgraduate experience at RMIT in Melbourne a few years ago.4

In the process of planning this talk I have actually realized that either I misunderstood or have misremembered the exact nature of these distinctions as they were presented to us then. I am, however, going to willfully stick with my own slight misappropriation here because I have found it useful. And usefulness is somehow at the heart of what I hope I am talking about today.

img#15

Research FOR design

Put simply, research for design involves the kind of essentially practical research we do to get a project started and completed successfully. It includes the immediate research that enables the design to happen. For example, given the budget, what printing process will be employed, what kind and weight of paper will be used, how will the book be bound?

img#16

Research ABOUT design

Research about design relates to contextual investigations that might end up influencing a specific project, a body of work, or even the trajectory of one’s practice in general. This might involve a developing understanding of historical precedents, of other practitioners, and/or of ideas and theories that influence not only the work, but also the way the work is made, where it is made, and how it is seen or distributed.

Research about design might also involve inquiries of a more philosophical or epistemological kind—“what is design, what is it about, what is it for, and why do we have it?”5

img#17

Research THROUGH design

But it is research through design that is of most interest to me here today. Because it is research through design that proposes that designers are actually engaged in researching while in the act of designing. That designing is a process of inquiry-in-action, a process whereby the designer is in a constant dialogue with that which is being designed. A process that constantly throws up new questions and demands new understandings, new conclusions.

We learn about design by doing design. So, in a sense, the design is the research. The practice is the research, and the research is the practice.

While, for obvious reasons, this is an idea generally accepted by disciplines that are heavily practice-driven, it remains contentious within the broader community of the university and within the framework of the PBRF.

And, to be honest, sometimes I’m not even sure I buy it? I want to, but I struggle with it sometimes. Why?

img#18

Dutch graphic designer, Daniel van der Velden, has used a Japanese whaling ship with RESEARCH painted on the side to show how the word ‘research’ can be used as a cover up—to hide or dissociate true intentions. He says:

“This is, I think, comparable and analogous to what is at risk of happening in art and design practices today. That risk is that we start naming them research practices while what’s going on below the surface is business as usual.”6

This is interesting because van der Velden’s observation aligns quite nicely with the 2012 PBRF Quality Evaluation Guidelines which exclude “routine professional practice”.

So, business as usual, routine professional practice—these are not, it seems, activities of research. The common thread here is routineness or usualness. For a practice to be research we can assume therefore that there must be something unusual about it, and that it should depart from routine.

img#19

As I have touched on earlier, when Jonty and I first began talking seriously about making a publication together one of the driving factors for us both was a general dissatisfaction with the position we found ourselves in—a deep malaise with ‘business as usual’. And from the beginning The National Grid was a project through which we imagined we might reinvent ourselves—a break in routine.

The National Grid, as a publication, more obviously involves aspects of research for or about design. There is a lot of practical stuff involved in just getting it done, and a lot our content is contextual and/or historical in nature.

However the learning that has been the most important for me has come directly from my working on the project—new understandings about agency, community, and a more holistic view of practice, that I have written and talked about elsewhere.

img#20

Looking back I think I can argue that The National Grid, as a project, has involved a more-or-less ‘systematic investigation’ that has led us both to new conclusions. And that that, in return, has enabled us to contribute to a bigger, broader conversation about possibilities and alternatives for graphic design practice.

Research may be an elusive and contestable term. Yet despite my struggle with it, I do feel quite comfortable standing here and telling you that The National Grid is a research project.

img#21

The End

I must be nearly out of time, so let me try and wrap this up if I can...

I recently returned to Canterbury University after having gone to teach design at AUT in Auckland for a couple of years. It was a strange experience interviewing for a job I’d already had just two years ago. I got the job. But, when I was offered the job by the then Head of School, it came with a strict warning—that my research wasn’t really “up to scratch”.

This wasn’t totally unexpected—it has been notoriously difficult, if not actually impossible for graphic designers to score under the current framework of the PBRF. And Canterbury University had a new mandate to not hire anyone who they thought might not score. Anyway I accepted the offer and took very seriously the advice that I might begin a PhD and look at writing articles for academic journals. There was no beating about the bush—The National Grid was going to be no good as a research output here.

And then a funny thing happened...

Later on that same year I was nominated for a ‘research award’. And then right at the beginning of this year I actually won this research award. And guess what it was for? It was for my work on The National Grid.

Confused? So am I.

And so here, it seems, I am—still lost somewhere in between the dictates of academia and my own twisted version of a ‘professional practice’ (one that exits predominantly on grants and subsidies rather than clients and briefs). But it is importnant for me to point out that the difference, now, compared to finding myself in this position ten years ago, is huge actually. Because now I can more confidently claim to in fact have a practice. A practice for which I can claim some sort of ownership, a practice over which I have some control.

And this—this sort of practical agency—is what I really would like to be able to pass onto my students.

I don’t really care if they ever get jobs... actually that’s not true. I do imagine them engaging in commercial practices—in studios, even advertising agencies—but when they do, I hope that they might find a way to work within them that is definitely not, as Daniel van der Velden would say, “business as usual”.

Thanks.

Footnotes

Tertiary Education Commission website, accessed 4 August 2012. http://www.tec.govt.nz/Funding/ Fund-finder/Performance- Based-Research-Fund-PBRF-/ ↵

Ibid. ↵

Oxford Online Dictionary, accessed 4 August 2012. http://oxforddictionaries.com/ definition/english/research ↵

I took Peter Downton’s ‘Research Methods’ class at RMIT in 2004. His book Design Research is structured according to this distinction of for, about, and through, although “more effort is expended on a discussion of researching through designing.” Downton, P. (2003) Design Research, RMIT University Press, Melbourne, Australia, 2003. ↵

Ibid. p.36. According to Downton this is what constitutes research ‘about’. He wouldn’t include contextual and historical research here like I have. ↵

Van der Velden, D. (2011) ‘Research and Destroy’ in Graphic Design: Now in Production, Walker Art Center, USA, 2011.It is worth mentioning here that I don’t think this “naming them research practices” necessarily always comes directly from artists and designers, but rather from the institutions that they work for or aspire to. ↵