Ideological object – Christopher Thompson

Edited and designed by Max Hailstone 1985

Max Hailstone’s book Design and Designers was published in 1985 under the aegis of the Christchurch printers Griffin Press and the New Zealand Industrial Design Council, an organisation established in 1967 by Act of Parliament ‘to promote the appreciation, develop- ment, improvement, and use of industrial design in New Zealand’.1 The book is both an eloquent and persuasive iteration of the nature of modernist design in the period following the Second World War and a demonstration of how design was practiced in New Zealand at the time.

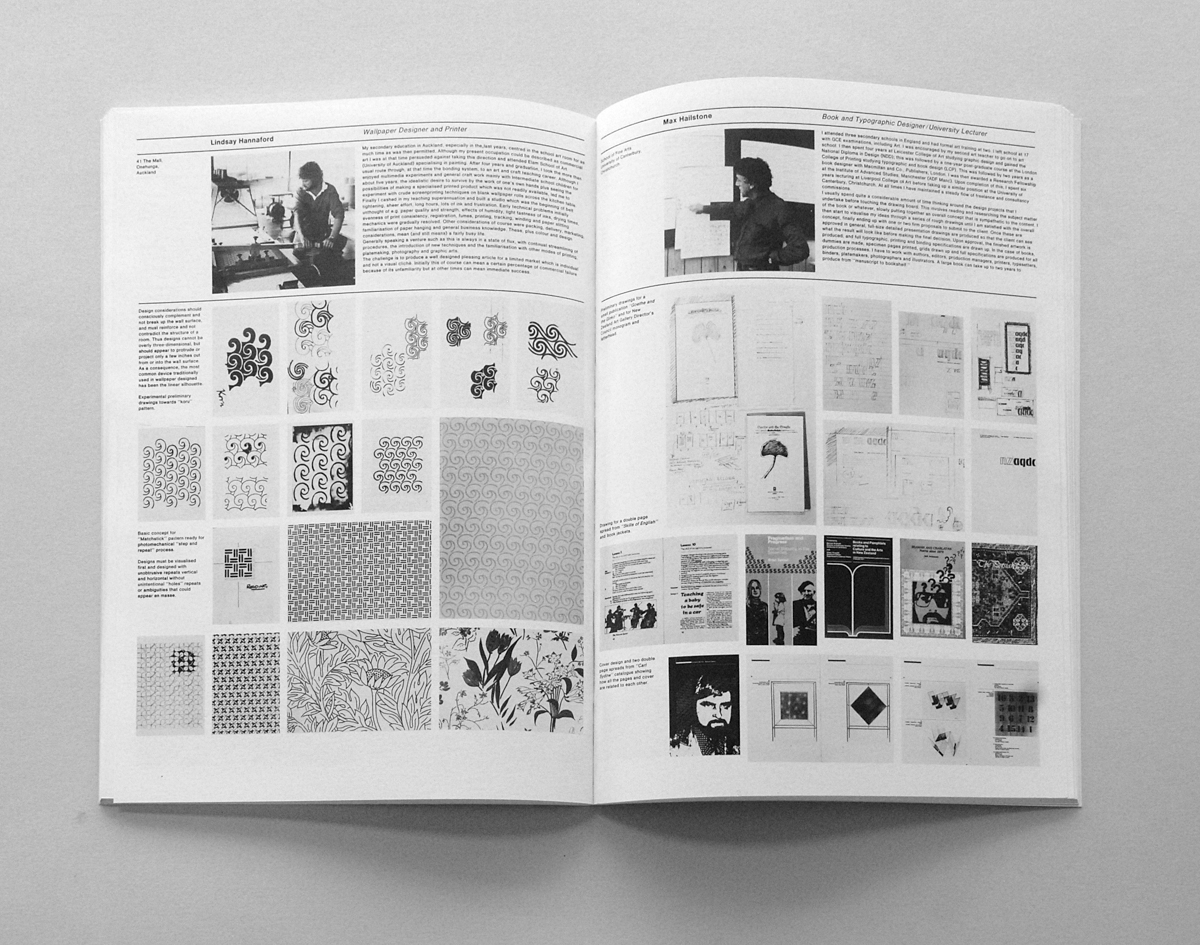

Divided into four parts, the 83 page, unpaginated, A4-sized book addressed the nature of design; exhibited a selection of forty eight designers—from product designers to shop window display artists— and their practices; outlined where one could train as a designer in New Zealand; and provided a short list of books and periodicals that would expand on the matters raised in the body of the text. For its target audience of secondary school students it would have been a useful book, outlining possible employment opportunities available within the relatively recently established vocation of design.

Despite being identified as a co-publisher and contributing five pages of the introductory text, including a brief forward by its chairman—the managing director of New Zealand Forest Products Ltd, Doug Walker—the New Zealand Industrial Design Council had little to do with the book. It made no mention of the initiative in its annual report to Parliament and failed to promote it. From the perspective of the Council, Design and Designers was an archaism; its key objectives were now aimed at satisfying the requirements of the corporate sector through engineering design, design management and quality assurance.

In pursuit of these business-friendly goals the Council’s foundation director, Geoffrey Nees, who was closely identified with its instigators, Bill Sutch and Philip Proctor, was dismissed.2 Publication of the Council’s magazine Designscape, previously recognised as “an authoritative and influential source of all information on design” and, at one stage, its “main publicity vehicle and revenue earner” was discontinued.3 And a new form of ‘corporate membership’ was introduced in a futile attempt to diminish the need for government funding.4

The Council’s new vehicle for publicity was the Prince Philip Design Award, which focussed on gratifying the manufacturing sector’s craving for recognition, rather than promulgating the benefits of design; it was a marketing opportunity for businessmen who had no interest in design, enabling them, and their wives, to indulge in self-aggrandising social functions under the benign, if remote and fleeting, glance of British royalty.5

But for all its attempts to embrace the chimera of market efficiency, the Council was abolished in 1988 amidst the fourth Labour government’s bonfire of the relics of the command economy. Like the New Zealand manufacturing sector that it had been set up to serve, the Council’s immolation was brought about as much by its own inept governance as it was by the government’s ideological commit- ment to free market liberalism.

Hailstone’s educative text, with its emphasis on function and process was a legacy of the earlier Council, which conceived of design in the modernist paradigm as enabling a process between producer and consumer. His view of the practice of design reflected both his background as a graphic designer trained in England and his status outside local power formations: he migrated to New Zealand in 1973 and worked as an academic at the University of Canterbury. The sort of design thinking that Hailstone brought with him and was seeking to impart with his text was metropolitan, informed and humanitarian, values that the Council no longer represented. Moreover, Design and Designers encapsulated an ideology entirely alien to those in the public and private sectors intent on implementing the agendas of free market liberalism in this small, uncritical, provincial outpost.

Footnotes

New Zealand. Parliament, Industrial Design Act, 1966. The Christchurch printers should not be confused with the eponymous Auckland Press established by the typographers Ron and Kay Holloway in 1938. ↵

Christopher Thompson, ‘Modernizing for trade: institutionalizing design promotion in New Zealand 1958–1967’, Journal of Design History, 24:3, 2011, 223–239,pp. 230–231. ↵

New Zealand Parliament, ‘Report of theNew Zealand Industrial Design Council for the year ended 31 March 1979’, Appendix to the Journal of the House of Representatives, G16, p.5. ↵

Nees was dismissed in May 1982 by the then chairman of the Council, James Collins—marketing director of Skellerup Industries Ltd—although the announce-ment of his ‘retirement’ was delayed until August. Designscape, by then a travesty of what it had been in the 1970s, ceased publication in 1983. Corporate membership was introduced in 1984 ‘to secure further support and participation from New Zealand industry’. ↵

The finalist was selected by the Duke of Edinburgh and the winner announced ‘by telecast from London’ to an audience at the Avalon Television Studios.See: New Zealand Parliament, ‘Report of the New Zealand Industrial Design Council for the year ended 31 March 1984’, Appendix to the Journal of the House of Representatives, G16, pp. 2–3; A King, ‘Pioneer is farewelled’, Howick and Pakuranga Times (30 April 2009). http://www.times.co.nz/news/ pioneer-is-farewelled.html Accessed 24 July 2012. ↵