To Think is to Speculate with Images: Rosicrucian linguistics revisited as semiological discourse – Bruce Russell

Ironically, in the digital era, the concept of the analogue takes on a new and more poignant resonance. Now that more and more of human knowledge is in the process of being translated into a language of binary signifiers, able to be decoded only through the interface of a machine, the relationship of res et verba, words and things, takes on a renewed charge of meaning. The last time in western culture that this relationship seemed central to all knowledge was at the dawn of the modern era. In the second half of the seventeenth century many of the sharpest minds of the times were preoccupied with the need to clarify once and for all what were the relative roles and ontological status of signifiers and things signified.1

For Leibniz and Descartes, Newton and Urquhart, these questions revolved around the great dream of a reformed language, a sermo purus which would recapture the magical union of names and things possessed by the language that Adam spoke in the garden of Eden.

The quest for a reformation of language brought together many of the disparate strands in the intellectual landscape of the early Modern period. It was believed that the new science could not advance without an unambiguous language to clearly express the essence of things and their relationships. The ideal was for a ‘philosophical language and real character’, the analysis of which would in turn reveal facts about reality itself.

Further, it was felt that the chimaera of religious unification could be attained if only debate could be conducted free of terminological confusion and ‘logomachies’. In the same way it was also hoped that political strife and the epidemic of war could be curbed by the acquisition of a language in which everyone would have to tell the truth. Up until the triumph of the ‘new science’ towards the close of the seventeenth century, the ethical/religious/magical aspirations were pre-eminent, and the search was clearly for a new universal ursprache. Post-1680 the goals of the language reformers narrowed to the search for a workable logico-mathematical notation, which bore fruit in the infinitesimal calculus, symbolic logic, and ultimately, the binary language of the computer.

The overall ethos of this enterprise continued to derive from the global goals of the language reformers of the earlier period, but the distinctly chiliastic tendency and magico-religious motives were subsumed to a more recognisably ‘modern’ enterprise, albeit one with clear antecedents stretching back to the middle ages.2 The post-Renaissance school of linguistic theory has been dubbed ‘Rosicrucian’ by Ormsby-Lennon,3 reaching its apogee in the political hothouse of Commonwealth England.

There are two conflicting traditions at work here, stemming respectively from Plato and Aristotle.

For the latter the origins of language lie in human conventions assigning sounds (words) to objects (things). For Aristotle there was no inherent relationship between the two, merely an accepted convention that gave meaning to essentially arbitrary associations. This is an instrumentalist theory of language, which is recognisably ‘modern’. It formed the intellectual equipment of most ‘serious’ language reformers of the seventeenth century, whether merely involved in the creation of a new alphabet (or ‘universal character’), or of an entirely new philosophical language.4

The Platonic conception, on the other hand, posited an inherent and necessary relationship between things and their names. In this view, words participated essentially in the nature of the objects they described. On this essentialist theory depended the whole structure of post-Hellenic magic, epitomised by the Kaballah, which elevated the Hebrew language and alphabet to the status of a map of the universe on a scale of one-to-one. Fundamental to this perspective was the belief that words were not merely analogous to things, they were identical with them. Thus, by knowing the right name of a thing, one could have power over it—to manipulate words was to manipulate reality itself.

During the Renaissance this tradition was powerfully extended to include the visual image, in a seamless continuum between things and their linguistic and artistic representations.5 Ormsby-Lennon has shown how these ideas are epitomised in the ‘book mysticism’ of the Rosicrucian Manifestoes. In these seminal statements of magical ultra-science the identity of res et verba is expressed through the metaphor of ‘the book Nature’. Nature (reality) is conceived as a vast book—which will yield all its secrets (and by analogy, all power) to any initiate who can read its language. “Although that great book of nature stands open to all men, yet there are but few that can read and understand the same.” 6

This conception of a mystical reading of, or union with, nature—achievable by initiates—was eagerly taken up by radical Puritan sectaries in England during the 1650s. They associated the sermo purus of the book of Nature both with the Pentecostal tongue conferred by the Holy Spirit and with the Adamic language spoken before the fall of the Tower of Babel. For them (as previously for Jacob Boehme) the New Tongue was also the Old Tongue, to be resurrected by divine grace mystically imparted to the Saints in the Latter Days. At its most extreme this conception went beyond the verbal altogether, and the new language was conceived as a post-verbal ‘language concrete’, synonymous with objects and images. Symptomatic of this was Walter Charleton’s call in 1650 to the righteous to “quit the dark Lanthorne of Reason, and wholly throw (them)selves upon the implicit conduct of faith”.7

This kind of mystical and epiphanic reform of language is profoundly anti-rational, and assumes an inherently teleological and ethical structure of the universe. Only if we assume such an intentional unity in the world can we assume the political programme of the puritan radicals, expressed in the equation: new language = new world = new city of God.

This can also be understood as a pair of related trinities:

right thought = right action = right language

right universe = right religion = right polity.

Of course the ultimately tautological nature of such ‘Rosicrucian’ philosophy betrays its methodologically unsound extension of analogy into identity.8

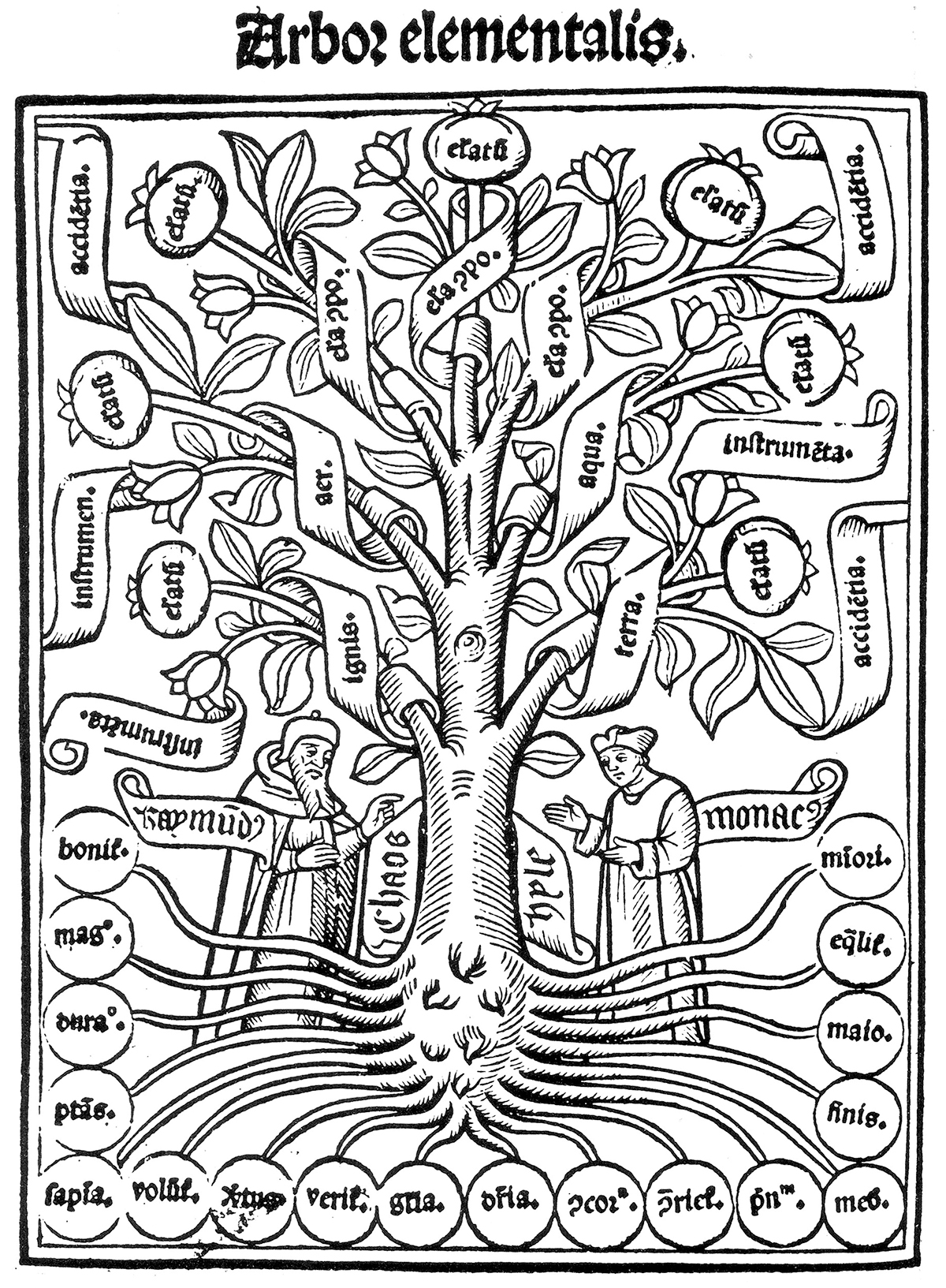

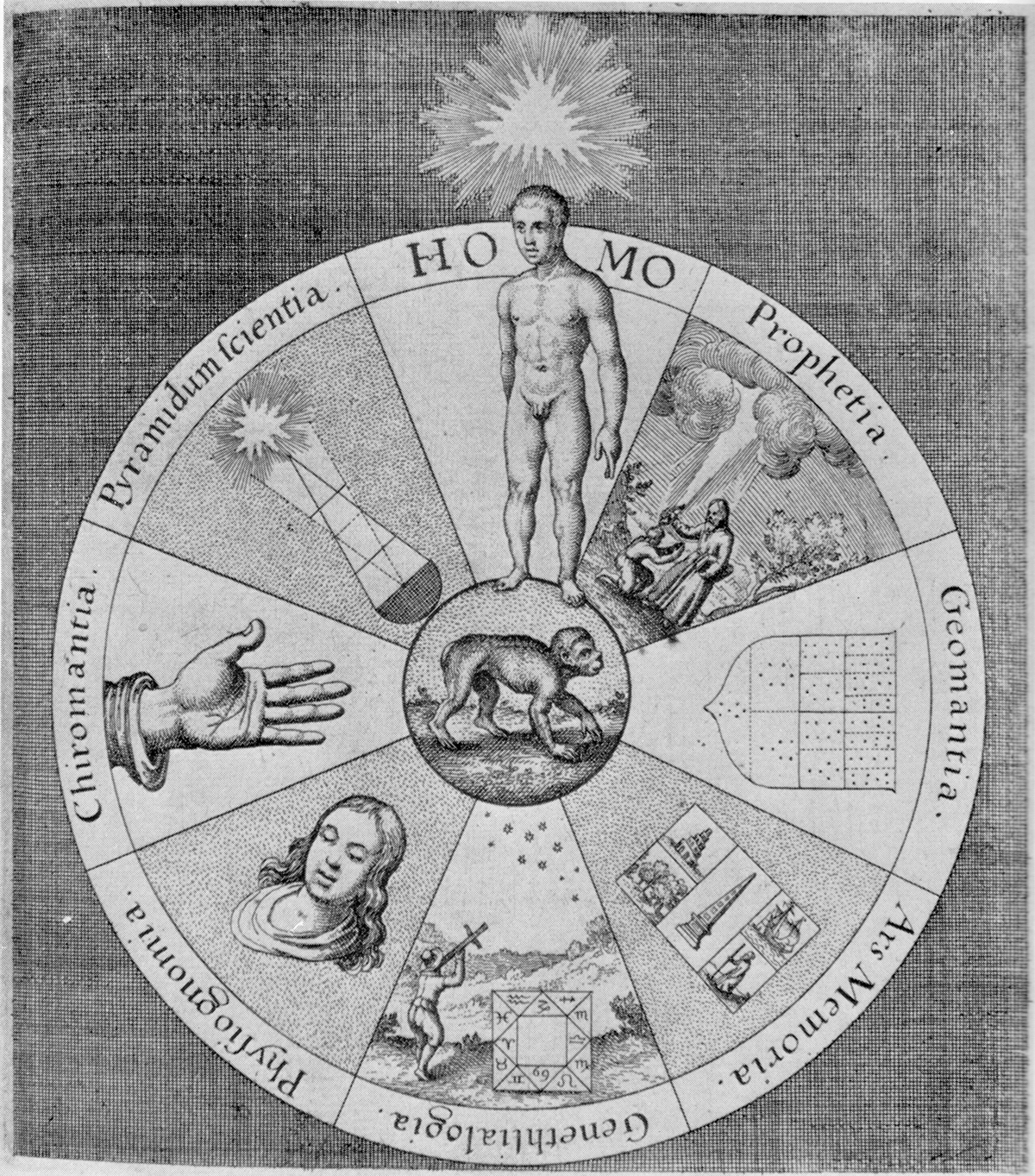

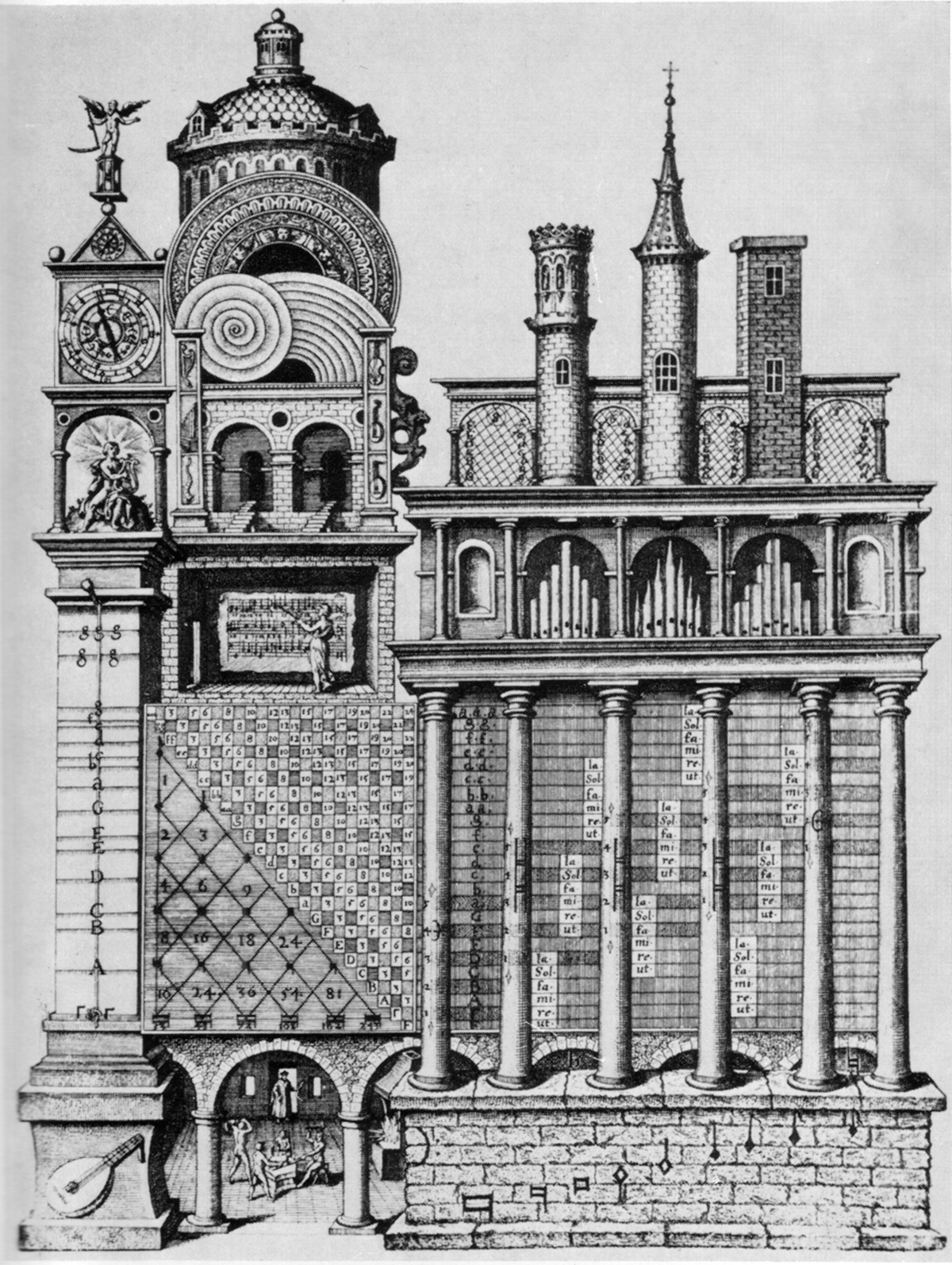

Nonetheless, the goals of these mystical linguistic reformers remain beguiling, and by an extension of their epistemology from the realms of language and the visual arts to that of music we may attempt an inversion of their dialectic into a digestable and ultimately usable form. Westman has written persuasively, in elaboration of Gombrich’s thesis, of the centrality of the diagram to the philosophy of the quintessential ‘Rosicrucian’, Robert Fludd.9 He argues that Fludd develops the Renaissance obsession with the hieroglyph to the point where the diagrams in his works bear the main weight of explaining his ideas. In effect he epitomises the argument of Giordano Bruno, advanced in his works on the art of memory, that “to think is to speculate with images” (intelligere est phantasmata speculari).10 Here Aristotle is being quite deliberately mis-cited by the ‘naughty magus’. What ‘the Philosopher’ originally meant by this was that all ideas are at base sense impressions, but Bruno is turning the tag around by associating it with the Renaissance neo-Platonic tradition, and arguing that all thought is supra-rational, ie. it occurs at a higher level than mere reasoning (and words), best represented by pictorial images. In effect he argues, and Fludd follows him, that language (post-Babel) is less well adapted to communicating a profound level of inter-subjective meaning than images (properly chosen and magically-constituted)—which somehow embody the virtue of real things. The only language that could match the utility of this would be a reconstituted lingua Adamica or ‘true kaballah’.

It is in this sense that we aspire to an instant communication of human reality by means of free music. Music constructed according to the rules of academic tradition—for all that it evokes a complex of Aristotelian instrumentalities (that is: conventionally accepted meanings)—runs the risk of putting too much premeditation and intellectual mediation between musician and listener. These are impediments to a direct, one-to-one human communication, happening in real time and space. As such, they are the equivalent to the “dead paper idols of creaturely-invented letters” railed against by Puritan language-critics.11

It is only once this dead weight of tradition and artifice has been set aside that human subjects can communicate directly. At that point the search can be resumed for “a new language for ourselves, in which withal is expressed and declared the nature of all things”.12 The need is for a new musical vocabulary, which will transcend, if need be, intelligibility of a merely rational sort, in pursuit of a true “logopandocy, or comprehension of all utterable words and sounds articulate”.13

Footnotes

Introduction to V. Salmon, The works of Francis Lodwick: a study of his writings in the intellectual context of the seventeenth century, London: Longman, 1972. ↵

For example, Leibniz was pre-occupied with the symbolic logic of Ramon Lull eg. F.A. Yates, ‘The Art of Ramon Lull’ in Lull and Bruno: Collected Essays Vol. 1, London: Routledge, 1982. ↵

H. Ormsby-Lennon, ‘Rosicrucian Linguistics: Twilight of a Renaissance Tradition’ in I. Merkel & A. G. Debus (Eds), Hermeticism and the Renaissance, Washington DC: Folger Shakespeare Library, 1988. ↵

J. Knowlson, Universal Language Schemes in England and France: 1600-1800, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1975 (esp. Ch. 3). ↵

E.H. Gombrich, ‘Icones Symbolicae: the visual image in neo-Platonic thought’, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, xi, 1943, p.163. ↵

‘Confessio Fraternitatis’: quoted in the appendix to F.A. Yates, The Rosicrucian Enlightenment, London: Routledge, 1972, p.257. ↵

W. Charleton, ‘Prolegomena’ to his translation of J. B. van Helmont, A Ternary of Paradoxes, London, 1650. ↵

B. Vickers, ‘Analogy vs Identity: the rejection of occult symbolism, 1580–1680’ in B. Vickers (Ed), Occult and Scientific Mentalities in the Renaissance, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984. ↵

R.S. Westman, ‘Nature, Art and Psyche. Jung, Pauli and the Kepler-Fludd Polemic’ in B. Vickers (Ed). Op. cit. (esp. pp.180–201). ↵

F. A. Yates, The Art of Memory, London: Routledge, 1966, p.252. ↵

J. Webster, Academiarum Examen, London: Giles Calvert, 1654, p.26. ↵

‘Confessio Fraternitatis’ in F.A. Yates. Op. cit., loc. cit. ↵

Sir T. Urquhart, Logopandecteision, London: Giles Calvert, 1652, abstract of the First Book. ↵