For Favours or Apologies – Anna Dean

2007

Louise Clifton

Digital photograph

2007

Louise Clifton

Digital photograph

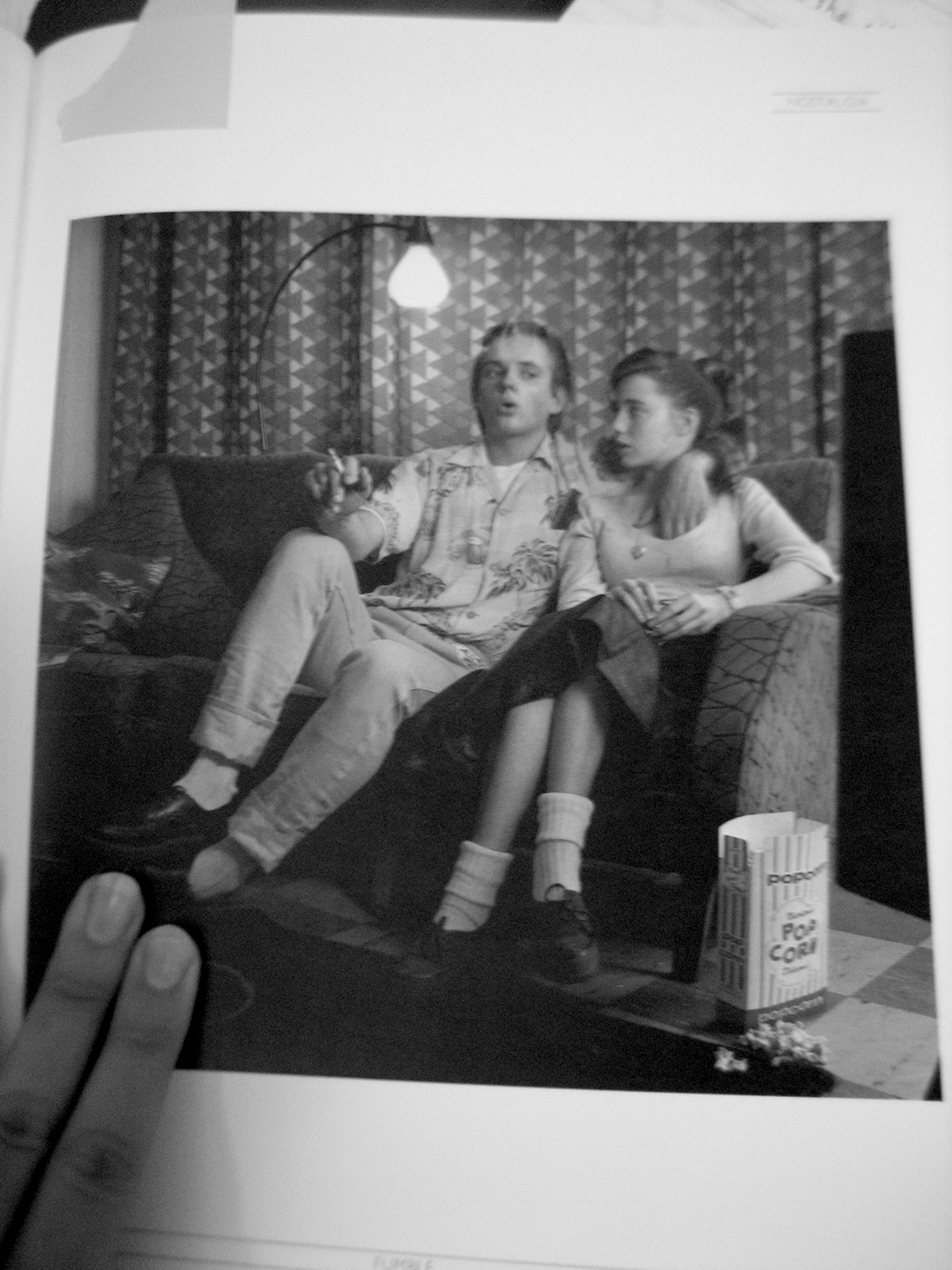

2005

Louise Clifton

Digital montage

(Inside spread for Luke Buda’s album Special Surprise)

2004

Louise Clifton

Digital photograph

(Cover of The Phoenix Foundation album Pegasus)

Fill a room with a bunch of tight-black-jean-wearing under-25-year-old graphic designers. Pack them in, hurl in one large brick and you’d be hard pressed not to hit one who doesn’t cite Peter Saville as, like, a major influence. Since the success of the Manchester biopic 24 Hour Party People, the consequent resurgence of interest in Factory Records, coupled with a range of 30-something design lecturers feeding their own generational Saville appreciation to fertile minds, his revivalist influence has reigned supreme for the last couple of years.

Now, as the trend appears to have spiked, it’s time to mention a far more pervasive and underlying influence in album art design caused by the relatively ‘untrendy’ work of earlier British design/photography outfit Hipgnosis. It’s also timely to reconsider what may constitute effective album cover art in the ‘Age of the Download’ and argue for an examination of the long-standing power of the single image portrait in a contemporary context.

As I sit typing on my Mac, iTunes blaring, iPod charging, album cover art appears to be facing an uncertain future. Standing on the precipice created by “Apple’s era-defining gadget” John Walters acknowledges, “the fear remains that album covers—perhaps albums themselves—may prove to be an historical blip, a short detour in the long history of music.”1 Faced with an endless stream of MP3’s and the soft striped tones of iTunes software, the incumbent weight of ‘days’ worth of songs seems to lessen the impact of the visual representation of one’s digital music collection. Sure you can browse your ‘album artwork’ with a forefinger swoosh but it’s not quite the same as flicking slowly through a stack of vinyl and being sidetracked by a striking image.

On the other hand, as Walters rightly notices, “The Rite of Spring didn’t need a sleeve design, nor did Duke Ellington’s East St Louis Toodle-Oo. With hindsight, the 78s of early jazz and folk music, with their ever-changing formats and anonymous paper bags (festooned with ads for hardware stores) are closer to today’s downloads than more recent music products.”2

The full circle from faceless production to disembodied digital file brings to bear the important question of ‘what’ the visual identity of any music actually is. While it’s not actually necessary for the listener to know what an artist looks like, album imagery, especially the portrait helps create a relationship or bond, a level of personal intimacy with the performer or musician. “For the buyer, the third stage is everything. Their experience of the music, their engagement and enjoyment will become wrapped up with the design and packaging and presentation of a particular album. Those graphics will come to mind every time they listen to the music, whether following lyrics, reading the credits, opening the package or merely glimpsing the cover image in the iTunes browser. Yet as downloads become a more substantial part of the creative music market, the single image may become more significant than the details of ‘packaging,’ changing the ‘music-image’ once more.”3

Although the relationship forming connection is a potent one I would argue that increasingly the single image (think Nirvana’s swimming baby or even Joy Division’s angel statue from ‘Love Will Tear Us Apart’) will take its seat sedately in a back catalogue of time and place, like the 12-inch vinyl cover and the jewel CD case.

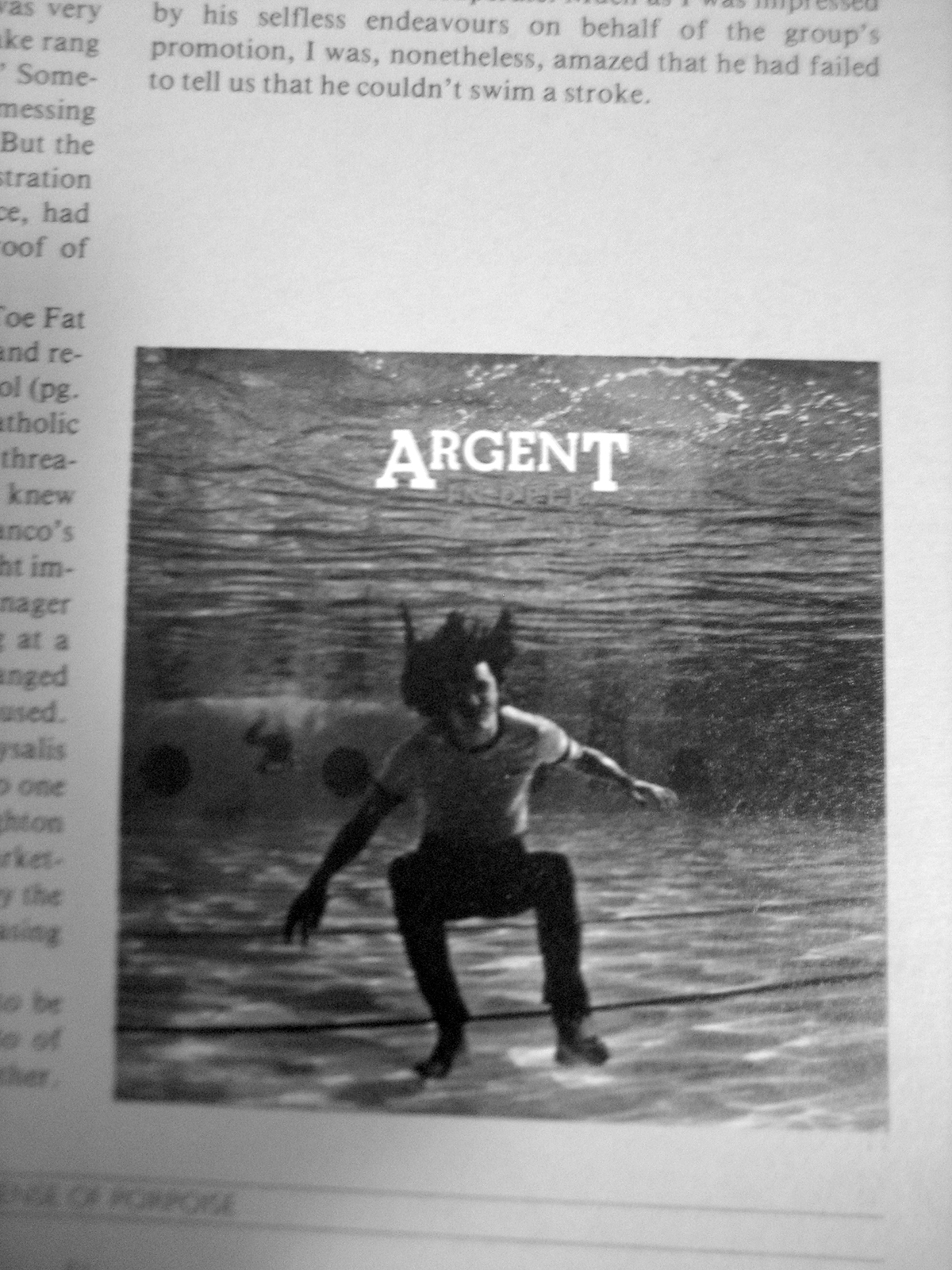

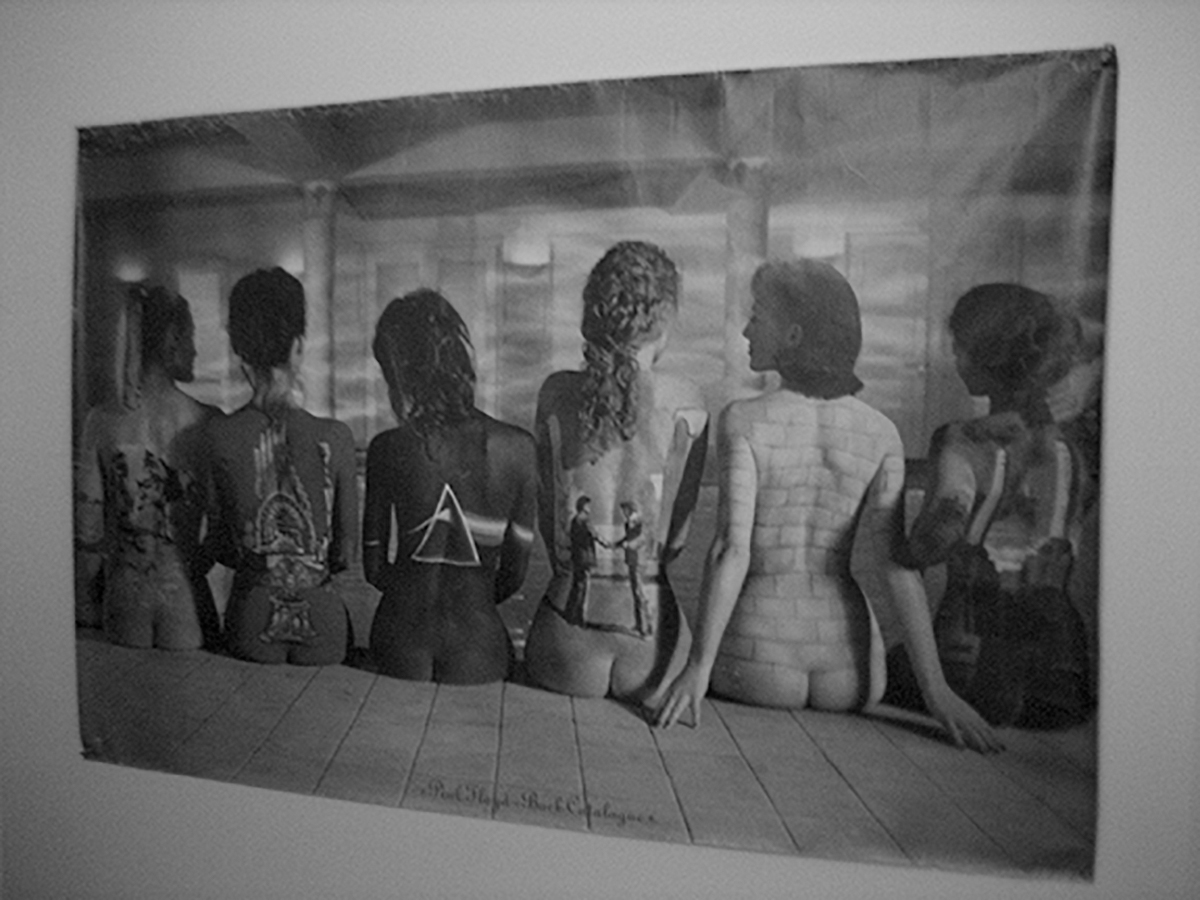

1973

Cover art by Hipgnosis

(Author’s photograph from the book The Work of Hipgnosis: Walk Away René)

Instead, in true po-mo celebration of the facade, the single image portrait, or the portrayal of the artist as ‘art object’, will rise to pre-eminence.

Arguably the ‘portraiture’ of artists is a concept long understood by the machinators of the Pop world. Madonna, and more recently Gwen Stefani, almost all hip-hop superstars, even the tragic B. Spears, all grasp the mass-market power of their brand and image (their walking, breathing portrait) and the importance of regularly updating and adding to their public image.

Prior to the 1960s album covers were characterised by staged photographs of performers either at their instruments or posed, usually smiling, in exotic locales or studios. The idea of musicians themselves being represented as ‘art object’ was yet to come. Although Elvis certainly splashed his jowls on enough album covers, creating a stage for others to jump up onto. The developments in sleeve printing and distribution allowed a greater platform for the advertisement of the musician, coinciding with changes in fundamental thought that portraiture could capture the soul or essence of the subject. As William Ewing writes in Face! The New Photographic Portrait, despite these claims of soul entrapment persisting for much of the twentieth century, “At the end of a long career of ‘making faces’ for clients who very much subscribed to those claims, Richard Avedon arrived at the conclusion that a portrait wasn’t ‘a fact’, but ‘only an opinion’. Stop asking for the inner being/essence/soul, he pleaded: ‘The surface is all you’ve got’. Alan Trachtenberg, looking at the new face photography more generally, concurred: ‘Now we distrust depths, interiors, hidden truths. Meanings lie on surfaces, artefacts of an occasion rather than truths about persons.’”4

This lack of depth and surface celebration sits perfectly with the airbrushed Stefani-esque beauties we are constantly exposed to today. In fashion photography models and figures engage with a viewer for a specific reason—to promote and sell a product. Anthropologists view the face as a biological ornament which signals valuable information to potential mates and these ornaments must be polished to perfection if seduction is to occur.5 Without being too cynical, this seduction by an artist’s successful portrait can then lead to increased album sales. Any 30-second viewing of current music television will unveil a veritable feast of thigh, breast and jiggling flesh.

Similarly as technology progresses, placing imagemaking and self-publication (MySpace, Facebook et al) into the hands of the masses, coupled with the facelessness of online communities, the power of portraiture as the new dominant index of faked reality (and conversely pop music) becomes stultifyingly obvious. Alter Ego: Avatars and Their Creators by Robbie Cooper and Julian Dibbell provides insight into our increasingly objectified ideal selves. Real life butchers, Japanese secretaries, middle-aged housewives and disabled people around the globe are casting off their physical selves to become idealised digital avatars. This virtual portraiture enables body-builder sized muscles, the ability to fly, bigger boobs and flawless skin in the short amount of time it takes for an upgrade.

The issue at hand for the contemporary image maker and graphic designer in the peripheral world of independent music, is how to create memorable portraits which transpose the mere façade and retain the dictates of self-expression for the portrayed, as well as the person holding the camera and wielding the Photoshop paintbrush. To paraphrase Walters once more, as packaging declines the music design which survives will most likely be in genres where the visuals forge a genuinely strong relationship with the sound, and where listeners expect imagery, content, information, style and depth in the way such music is presented to them.

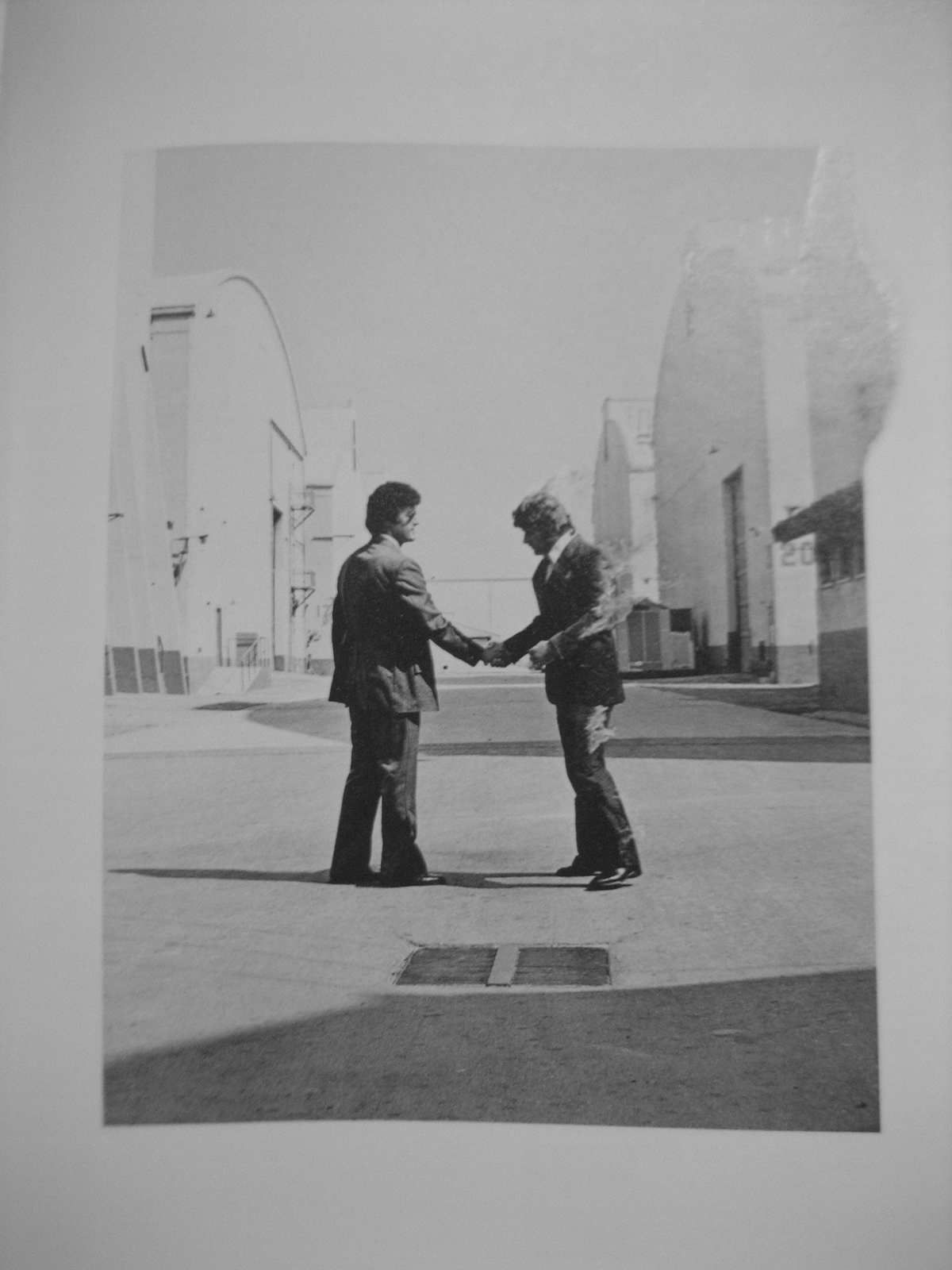

1975

Single cover

Cover art by Hipgnosis

(Author’s photograph from the book The Work of Hipgnosis: Walk Away René)

And so back to the overarching reach of Hipgnosis. Through the sheer quotidian exposure of their imagery it’s almost easy to overlook the guidance and magnetism provided by their contribution to the cannon. Their work is instantly familiar after endless hours of turntable-side childhood or teenage contemplation around the Western world. Who didn’t gaze at Pink Floyd’s 1975 album cover of the burning handshake and wonder how on earth did they do that? Did the guys wig melt onto his head? I remember thinking there must have been a giant paddling pool just out of the frame for the flaming man to belly-flop into, and have always loved how the man on the left is leaning, just slightly, away from the flames.

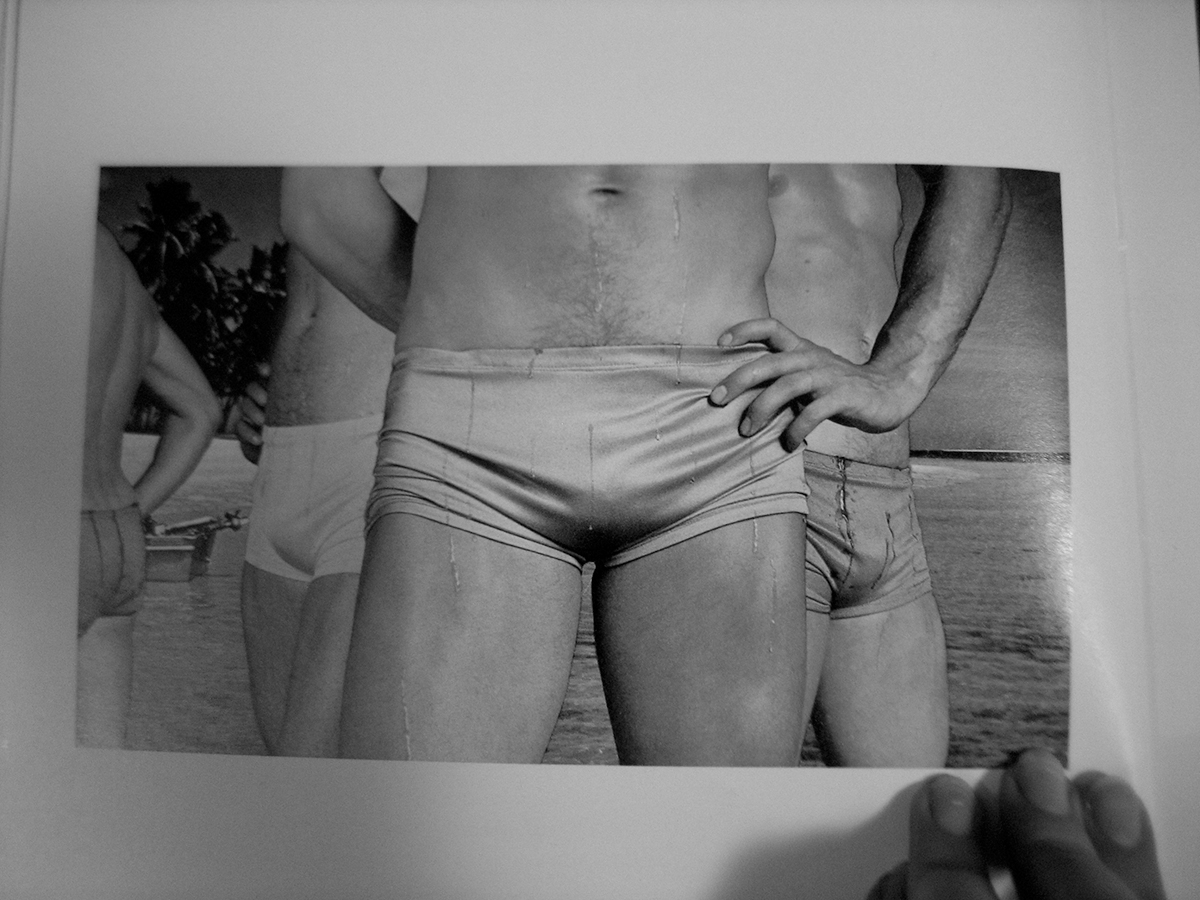

1975

Cover art image by Hipgnosis

(Author’s photograph from the book The Work of Hipgnosis: Walk Away René)

Yet it is Hipgnosis’ use of meticulous air-brushing and image manipulation that could be said to have left the greatest mark. Their approach to album cover art was predominantly photography-oriented, pioneering many innovative visual and packaging techniques. As Steven Cerio writes, their “surreal elaborately manipulated photos (utilising darkroom tricks, airbrush, retouching, and mechanical cut-and-paste techniques) were a film-based forerunner of Photoshop-ing.”6

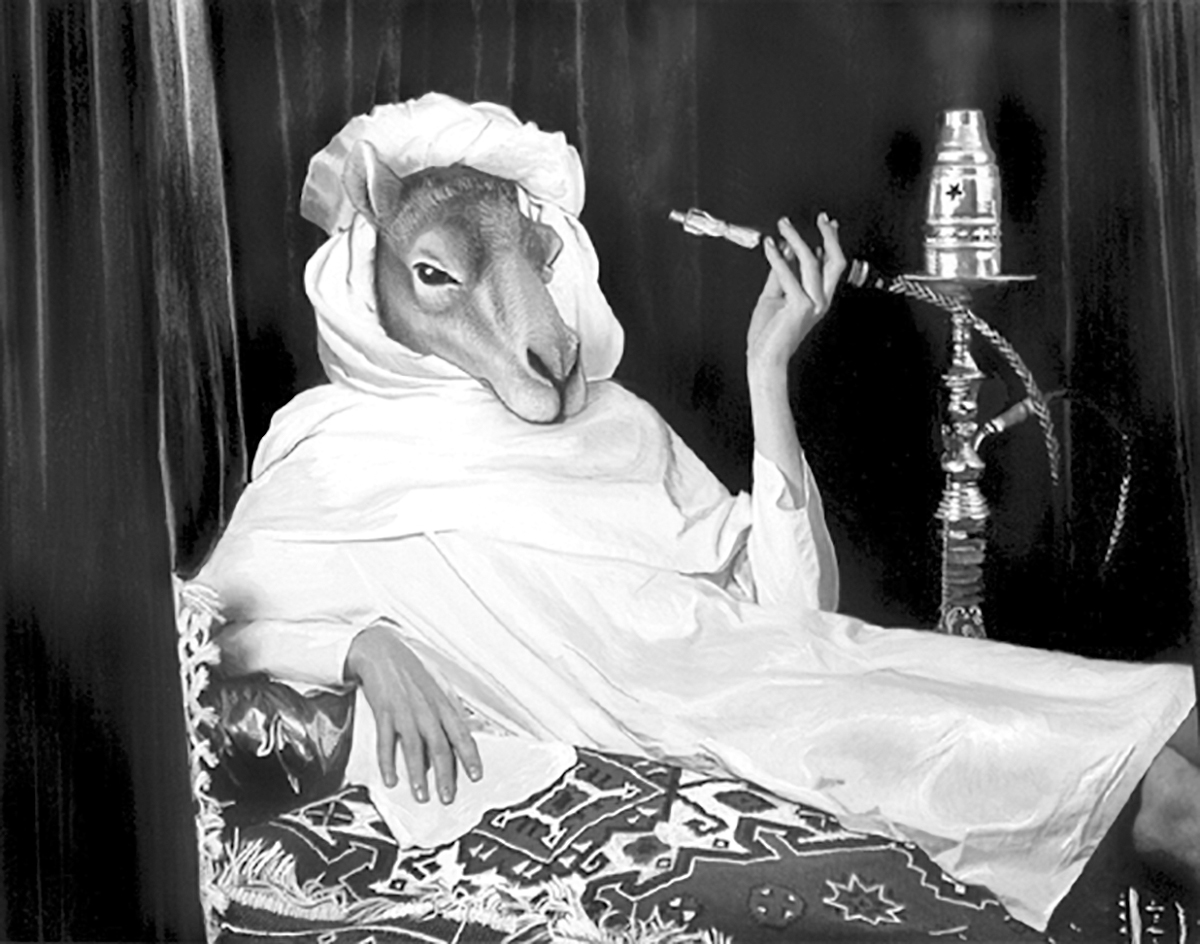

2007

Fast forward to the present of po-mo disco hyperreality, and we (at least I) get to the practice of one woman, Louise Clifton, based in the small town of Oamaru in the nether regions of the South Island of New Zealand, where she stands camera and Apple Mac in hand, tugging at the frames of reference created by the Hipgnosis troupe. In a world of pop-packaging, airbrushed hybridisation, tie-ins with Paul Smith campaigns, cellphone company rainbows and lollipop girls, Clifton is quietly making an impression as a sought-after image-maker for the independent music scene, skipping happily alongside her fine art photography practice.

Clifton’s portraits of musicians for her album cover art are a mixture of the attractive and the uncanny, the decadently glamorous and the obsessive. She uses language like ‘bright’, ‘hard’, and ‘ridiculous’ to describe her work. Clifton has produced imagery and design work for various underground New Zealand bands—all loosely based on the glamour portrait aesthetic, they range from the distinctly tungsten-lit old-Hollywood feel, to the 1980s Hipgnosis airbrushed hallucination.

Her ‘hard’, ‘bright’ work involves major digital retouching and her Photoshopped, shiny landscapes and false cyberscapes have a mystique all of their own. She creates surreal imagery of a “macabre pop ethos”, to borrow a phrase from Enjoy Gallery’s Marnie Slater. The flawless appearance of her figures is due to, quite literally, days of Photoshop work or meticulous handpainting, a process she finds “appropriately meditative”.

Her working process is multi-layered. Often starting out with a range of images she likes the look of, she sews costumes and makes props for her photographs, then combines them in the one image. Her work is characterised by a desolation and vulnerability. As she says in Nothing Magazine, “I do like taking photographs of people or humanoids that look a little lonely and uncanny.”7 The treatment of the artist as art object, coupled with the flawless appearance of advertising imagery taken to an 80s glamour apex appear to be the main strengths in her album cover art.

Significantly Hipgnosis’ cover photos often told ‘stories’ directly related to the albums lyrics. As Storm Thorgerson writes the team often tried to involve the artist in some kind of event or action, “If he agrees then it adds something apart from the purely visual aspect, but it is not often that he just happens to be the right person, or is even prepared to do it in the first place.”8 Clifton capitalises on this concept creating virtual landscapes or backdrops for her artists while remaining true to their distinctly independent image needs.

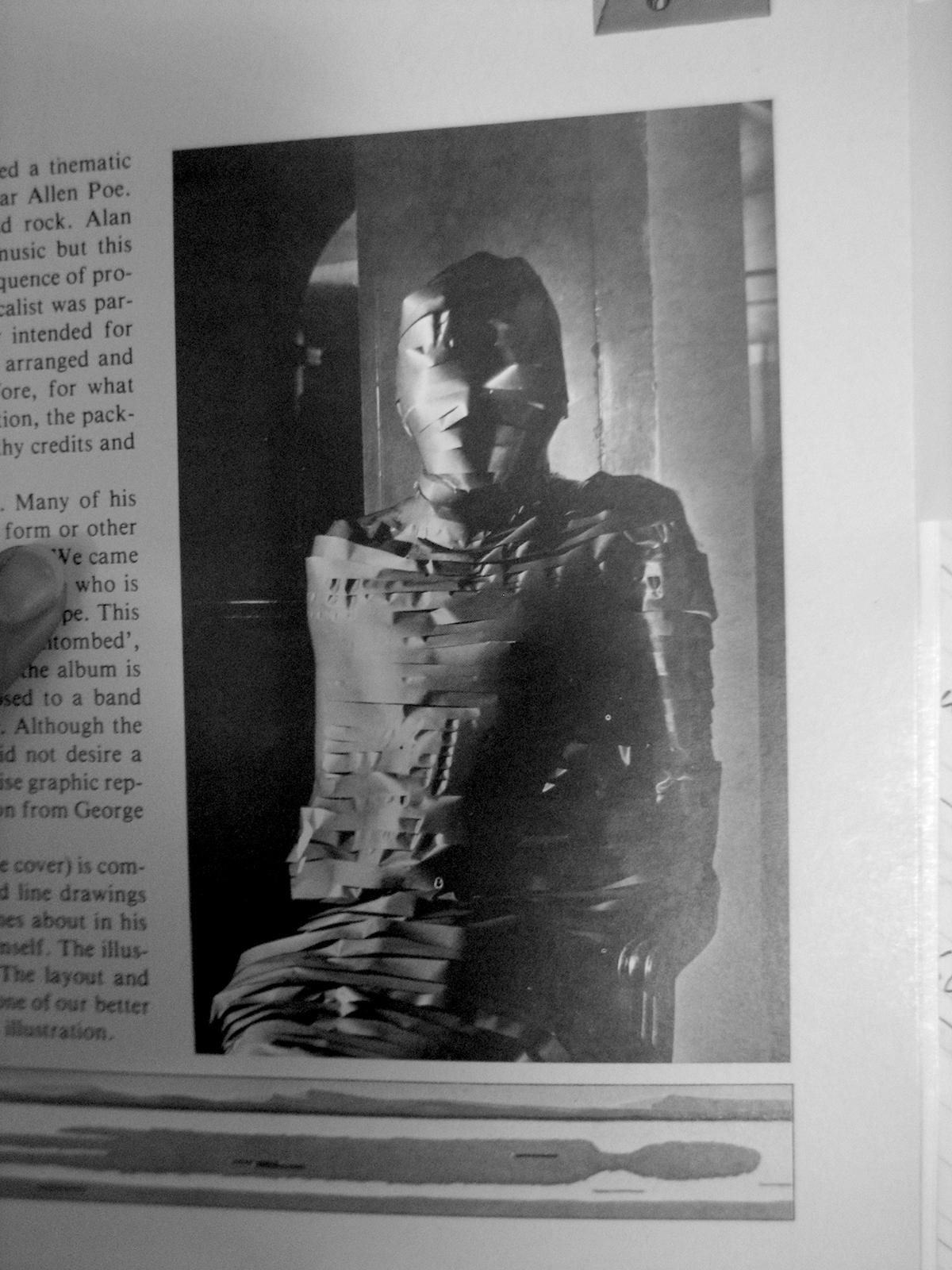

1976

Illustration eventually used instead of this photograph

(Author’s photograph from the book The Work of Hipgnosis: Walk Away René)

The boyish portrait for Luke Buda’s solo album Special Surprise is a direct copy of the New Zealand release of one of Christian-rocker Michael W. Smith’s albums. On the cover he is pictured in a pink and grey argyle sweater, jumping through an argyle backdrop with a “dicky, hard-to-define smile on his face”.9 Buda’s face is airbrushed to an Hipgnosis extreme, childlike and innocent, and he wears a creepy almost feminine looking jersey. The neckline reminds me of smelly Cats Protection League op-shops and cheese sandwiches as does his slicked down shiny hair. Yet as a figure he’s situated in a futuristic Hipgnosis-esque box. Is Tron or maybe Jesus about to burst through the mysterious blue light? Or is this Buda’s dream version of a tunnel to some electro-heaven where he can croon his mellow guitar pop and hopefully find a better sweater?

2005

digital montage by Louise Clifton

Similarly, Clifton’s treatment of the inside sleeve for his CD [see colour images below] is also a worthy tribute to the collage fantasies of a Hipgnosis future. Actually inspired by Vangelis designer’s vision of Heaven and Hell for their album of the same name, Clifton’s cyberscape continues the purple/blue electronic cage, disembodied eyes locking in the gaze of the listener. It really does raise the question—what planet is this guy on?

Completely disinterested in the girly or the sexy, many of Clifton’s photographs have moved to the futuristic from an earlier Gothic sensibility. This has been reinforced by her recent move south to the Victoriana capital of New Zealand, Oamaru. “Moving to a town where people live and dress ‘trad’ has made me realise I was reared on, and am 100% Pop.” It’s the perfect foil to the Aucklandness of well-known photographer Yvonne Todd. Where Todd celebrates the creation of the new individual in her photographs using models and various modes of disguise—“There was quite a bit of make-up and wiggery going on so it’s not really the person, it’s more like a character, they’re not themselves”10—Clifton deals directly with the possibilities presented by the artist’s physicality and their personality, infusing the character with a dash of the fictional and make-believe [see p.18].

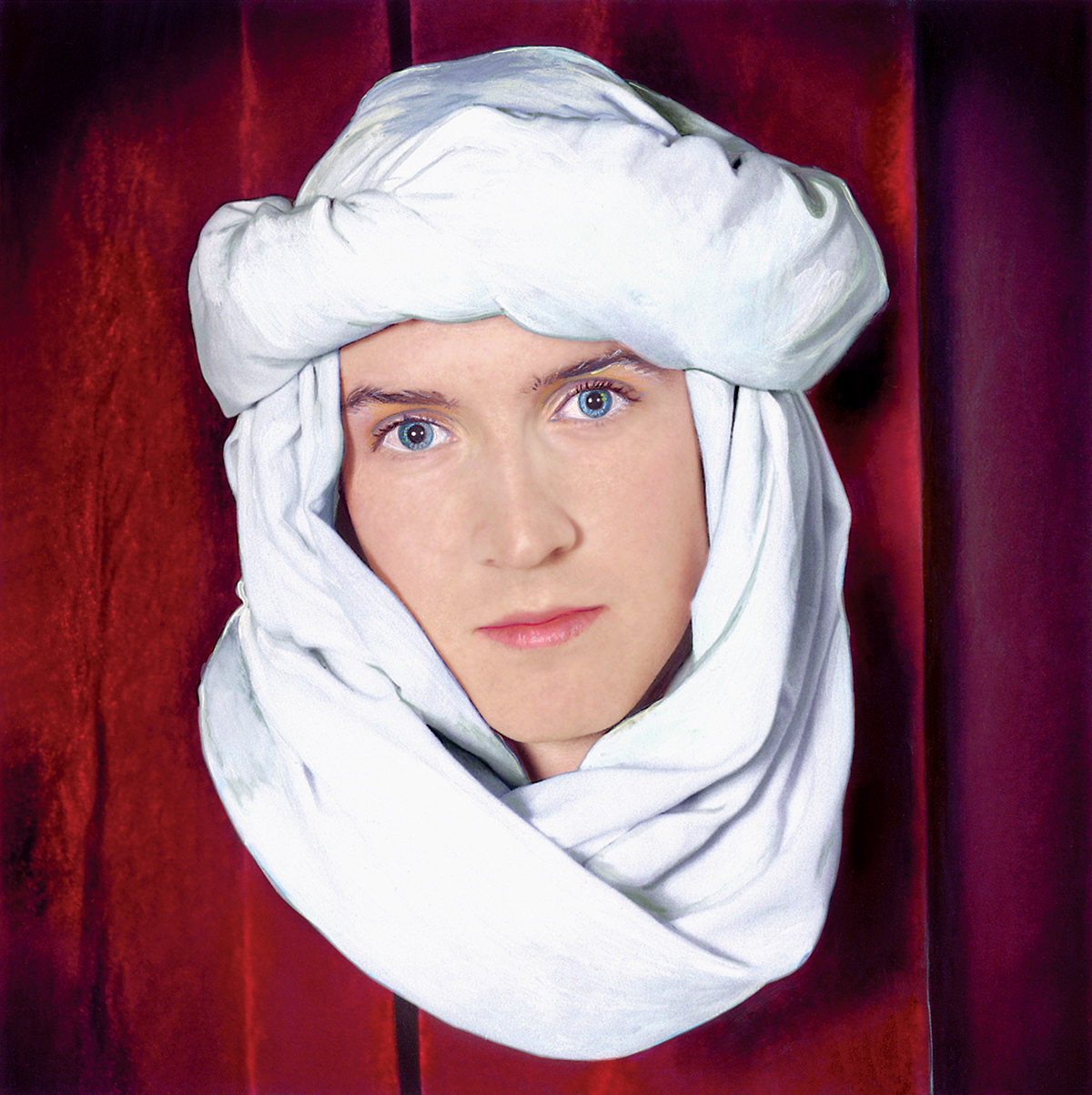

Her portrait of Lawrence Arabia starts with a simple play on the artist’s stage name, carried through to its full humorous potential [see colour images below]. Arabia wanted his face to be on the cover and his floating head image involved three full days of delicate hand-painting with a tiny brush. Using water colour dyes for the curtains, Clifton then painted in the headdress and eyes, undertaking this meticulous process of 1950s style touch-ups to achieve an airbrushed aesthetic, happy in the knowledge she had done it by hand rather than by computer. On the back cover a camel’s head pokes from the curtains (or desert tent) mimicking Arabia’s face on the cover. This make-believe desert scene captures the comic, the self-referential nature and theatricality of Arabia’s work to perfection.

2005

Hand-painted photograph/digital montage by Louise Clifton

A portrait requiring more careful consideration is the striking image of Dunedin-based solo artist Stefanimal [see colour images above]. As Ewing writes, “A portrait puts a head in a vice, and clamps it tightly for scrutiny of others.”11 This is a particularly loaded exercise when you’re a young person undergoing gender change. For Stefanimal’s promotional portrait Clifton spent time studying facial feminisation websites for instruction on how to feminise male facial features. Basic techniques include moving the brow forward, removing the adams apple and creating fuller cheeks. Clifton has already updated the image, recording the transition as she has watched her friend’s face change and hopes to revisit it in the future. Never one to miss the opportunity for humour, a fake moustache has been added, an emblematic medal of sorts, pinning the male marker on the beautifully soft pink face. For Stefanimal this gesture of “gender-fucking” was a way of adding some masculinity to the image “which was a bit too femme” for her tastes.

2007

digital photograph by Louise Clifton

With a dexterous click of the digital shutter Clifton treats her female subjects with much care and sincerity. Her treatment of solo Christchurch artist Bacherlorette [see colour images below] is appropriately staunch and intriguing—suiting her name and persona. The pose adopted and dress selected, arms folded, and proud, Bachelorette looks towards a future so bright her sunglasses cover the eyes. Yet the wacked-out pixellations hint at the sonic scope of the music and the performer. A common feature in Clifton’s images is a latent nostalgia for the Jetson’s futurescape we are yet to inhabit, and perhaps never will. Similarly Hipgnosis fantasy-scapes often imagined vast futuristic cities. Flying pterodactyls swoop through skyscrapers on the Quatermass cover, while a lone naked male figure contemplates a path through overpowering office blocks. Conversely a distinct nostalgia for an idyllic 1950s Teddy Boy suburbia also featured strongly, a common fascination during the 1970s.

1972

Cover art by Hipgnosis

(Author’s photograph from the book The Work of Hipgnosis: Walk Away René)

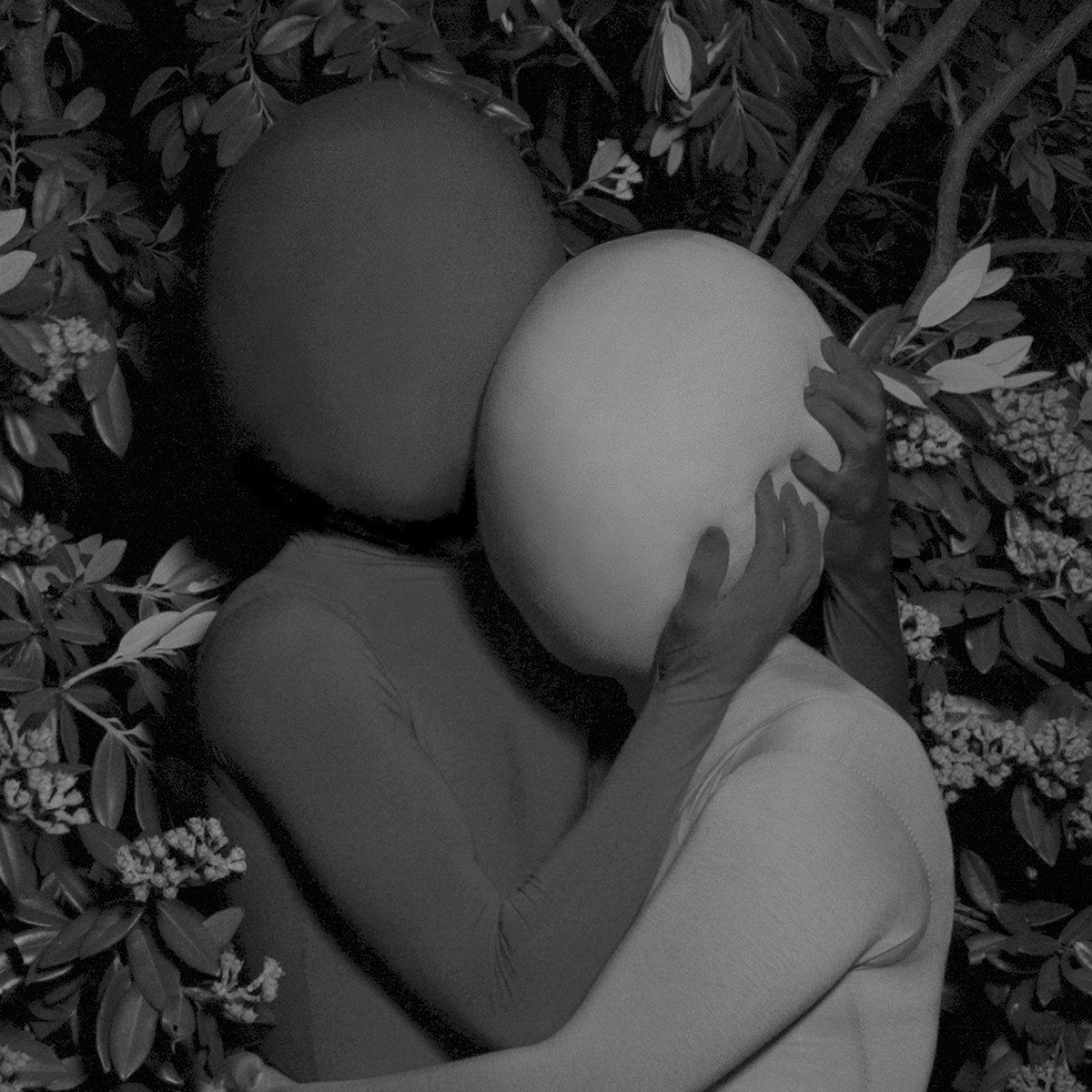

Interestingly, in Clifton’s artistic practice, much of her recent work, including a recent exhibition It’s a Wonderful Tonight at Wellington’s Enjoy Gallery (May 2007), has centered on the exploits of a faceless, humanoid figure [see colour images below]. A series of photographic portraits of a red man in skin-tight lycra, devoid of any distinguishing features, is possibly a reaction to the tiresome nature of dealing with others’ vanity. The red man poses and smirks under his red skin, as Clifton flexes her portraiture muscle with a nod to the work of Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama.

2006

Digital photograph by Louise Clifton

Used for US release of The Phoenix Foundation’s album Horsepower.

This image has subsequently been used as an album cover for New Zealand band The Phoenix Foundation, for the US release of their Horsepower album [see colour images above for the NZ release cover also by Clifton]. Initially inspired by the luscious foliage and strong colour of the infamous Roxy Music ‘beautiful-girls-in-see-through undies’ cover (photograph by Nicholas Deville), Clifton placed her faceless figure in the bottom of a garden hugging a fellow pink lady, offering calm and shelter, from what we’re not entirely sure, but the image raises all kinds of possibilities.

Hipgnosis were fortunate enough to be close friends with Pink Floyd, hence their foot-in-the-door invitation to design for the band’s second album A Saucerful of Secrets. This association led to a roll call of famous clients during the 70s and 80s. The team never charged a standard design fee but instead asked artists to pay what they thought the photographs and designs were worth. Clifton operates in a similar manner. As a friend and associate of various players in New Zealand’s indie music scene Clifton has the access to and, most importantly, the trust of a range of artists who have handed over their physical selves to her image control. The nature of the photographic portrait lends itself to a loss of power through the very basic dynamics of photographer and subject. One wields the apparatus while the other is ‘captured’. As Ewing notes, “Two human beings facing each other always involves a degree of psychological give-and-take. Sometimes the game takes the form of a face-off, as in certain sports, where both sides are equally balanced. Sometimes the photographer tries to dominate the exchange—after all, he wants people to admire his portrayal, rather than the actual man or woman portrayed.”12 Correspondingly the sitter can wrest back some control as their movement or lack of expression can force the hand of the photographer, nulling or harming an image.13 As a confidante of sorts Clifton enters into a personal exchange with her friends and has created a series of stunningly sympathetic and considered portraits.

The element of advantageous human relationships is often absent from design discourse yet these associations and collaborations form an integral part of the industry. For Clifton sometimes portraits are exchanged for favours or apologies. One was created when Clifton felt bad for moving out of a flat. By and large though all the images thus far are for friends for ridiculously small amounts of money. This suits the exchange system perfectly as these artists place their image in her hands to construct a promotional “face” far removed from the idealised portrait or avatar so common today. Neatly capturing Clifton’s prowess and the ability to provide a perfectly executed single image to add significant value to a musical experience, Mark Amery writes, “In the CD format, with the jewel case providing a series of frames, it’s a personal memento for the purchaser, like a contemporary equivalent of the miniature portrait painting or photograph. I’ve been thrashing the Lawrence Arabia album on my laptop, but I’m still yearning to go out and buy it encased by Louise Clifton’s excellent artwork.”14

In the end, there’s no argument that the ultimate selection and purchase of music by a listener will be based upon the sounds wrapped inside or digitally partnered with the cover image. Yet as Thorgerson notes, “In the end it may just be a matter of personal choice by the artiste—it’s not a proven economic necessity to have any particular kind of cover design—and perhaps it’s simply better news to have an evocative picture, whether portrait or abstract, rather than a boring piece of shit.”15

2005

Louise Clifton

Hand-painted photograph/digital montage

(Front cover of Lawrence Arabia’s self-titled debut album)

2007

Louise Clifton

Digital montage

2006

Louise Clifton

Digital photograph

Footnotes

John L. Walters, ‘Can design for contemporary jazz, world and experimentalmusic have a meaningful partnership with the musical content?’, Eye 63, 2007. ↵

Ibid. ↵

Ibid. ↵

William A. Ewing and Nathalie Herschdorfer, Face! The New Photographic Portrait, London: Thames & Hudson, 2006. ↵

Ibid. ↵

Interview with Steven Cerio—‘Storm Thorgerson, album cover artist who founded the design studio known as Hipgnosis’.

http://www.happyhomelandstore.com/interviews/thorgerson.htm ↵

Interview with Louise Clifton, Nothing Magazine #15, March 2007. ↵

Storm Thorgerson, George Hardie, and Hipgnosis, The Work of Hipgnosis ‘Walk Away René’, Great Britain: Dragon’s World Ltd, 1978. ↵

Brief conversation with Louise Clifton. ↵

‘Death, Rejection and the Fountain of Youth: Melancholy and Subversionin the work of Yvonne Todd’, White Fungus, issue 7. ↵

William A. Ewing and Nathalie Herschdorfer, Face! The NewPhotographic Portrait. ↵

Ibid. ↵

“Once I feel myself observed by the lens, everything changes: I constitute myself in the process of ‘posing’, I instantaneously make another body for myself, I transform myself in advance into an image.” Roland Barthes 1981, from William A. Ewing and Nathalie Herschdorfer, Face! The NewPhotographic Portrait. ↵

Mark Amery, ‘The gift of sound and vision’, Dominion Post, Friday May 11, 2007. ↵

Storm Thorgerson, The Work of Hipgnosis ‘Walk Away René’. ↵