You are Experienced: Jimi Hendrix—A Lyric Poet of the Era of Post-Industrial Capitalism – Bruce Russell

I’m always trying to connect things in my mind. I think a lot about culture and society, and the more I understand how things connect, the more I expect them to do so. I think trying to make sense of the world is a characteristically human failing, for which we have to thank religion, amongst other things. I find that things always do seem about to make sense. Or worse—they seem to already make a sense that I just can’t quite assemble in my mind. I grab a piece here, and a piece there, I match them up and just as it starts to form a recognisable image, the jigsaw turns into a manta ray and flies off across the roof tops as they sprout coral outcroppings among the satellite dishes. I’m sure you all know what I mean.

Last year I got heavily into Walter Benjamin, and everything became even more out of control. This article had its origin in a fairly typical example of this. I was told that my piece should have some relation to graphic design. At first I thought about how I’d read at least six books last year concerning Benjamin’s theory of experience, in particular, our experience of modern life. I was reflecting on this as I wrote a proposal for a contract to investigate the ‘user experience’ (or UX) of a major corporate website. This is something I do to make a living.

Now I don’t read Benjamin in order to more efficiently screw money out of publicly listed companies—or rather, I thought I didn’t, until recently. My interest is in the field of cultural studies, trying to make sense of stuff we do when we aren’t fixated on earning a buck. Specifically I’m writing a doctoral exegesis on the social utility of improvised sound work—which is something no one does for the money. And one thing led to another, as I idly speculated on the coincidence in terminology—user experience—experience of modern life—Baudelaire—Jakob Nielsen—until I experienced what Benjamin calls a ‘dialectical flash’: and then my mind split open, and out stepped Jimi Hendrix.

Now, you’re quite right—no one should get from Walter Benjamin (the guru of cultural archaeology) to Jakob Nielsen (the guru of user interface design) to Jimi Hendrix (the mother-fucking guru of groove). Suddenly I was back with the manta rays swimming over the rooftops. So I spent a bit more time getting my head around what might be the relation between these things. It wasn’t till I went over to my record collection and pulled out Are You Experienced that I began to see the connections.

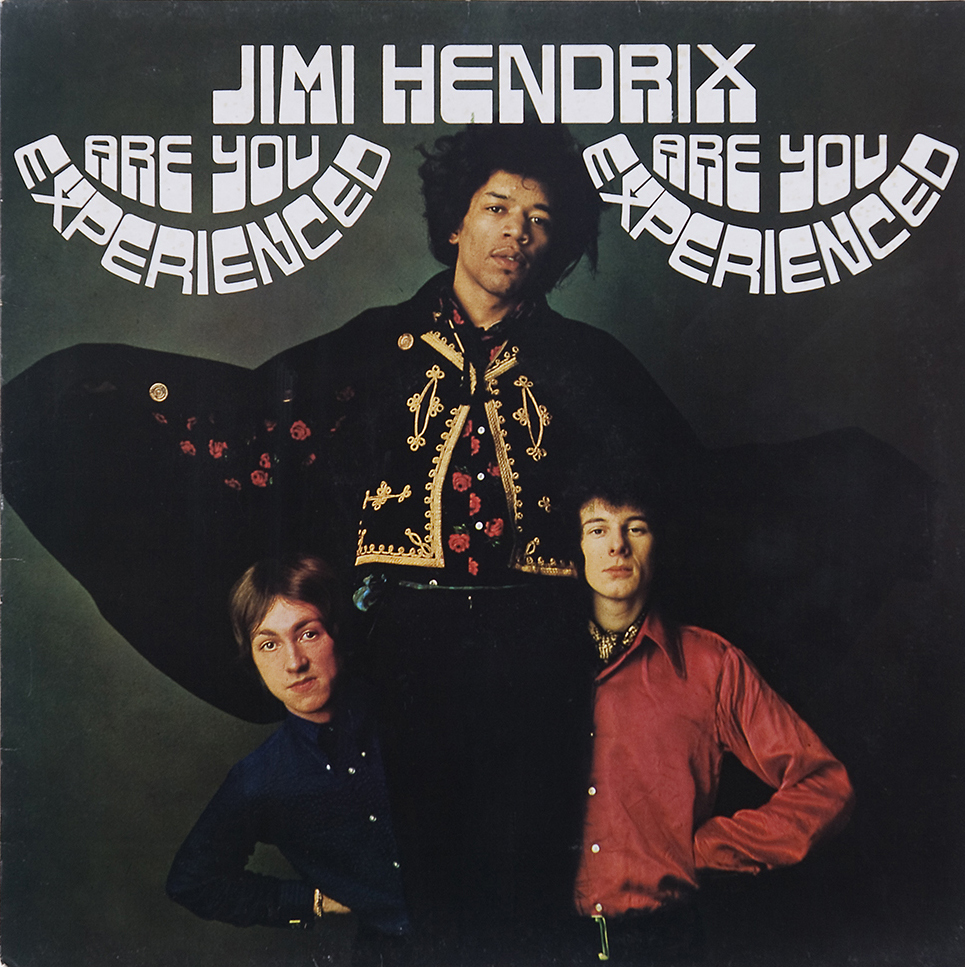

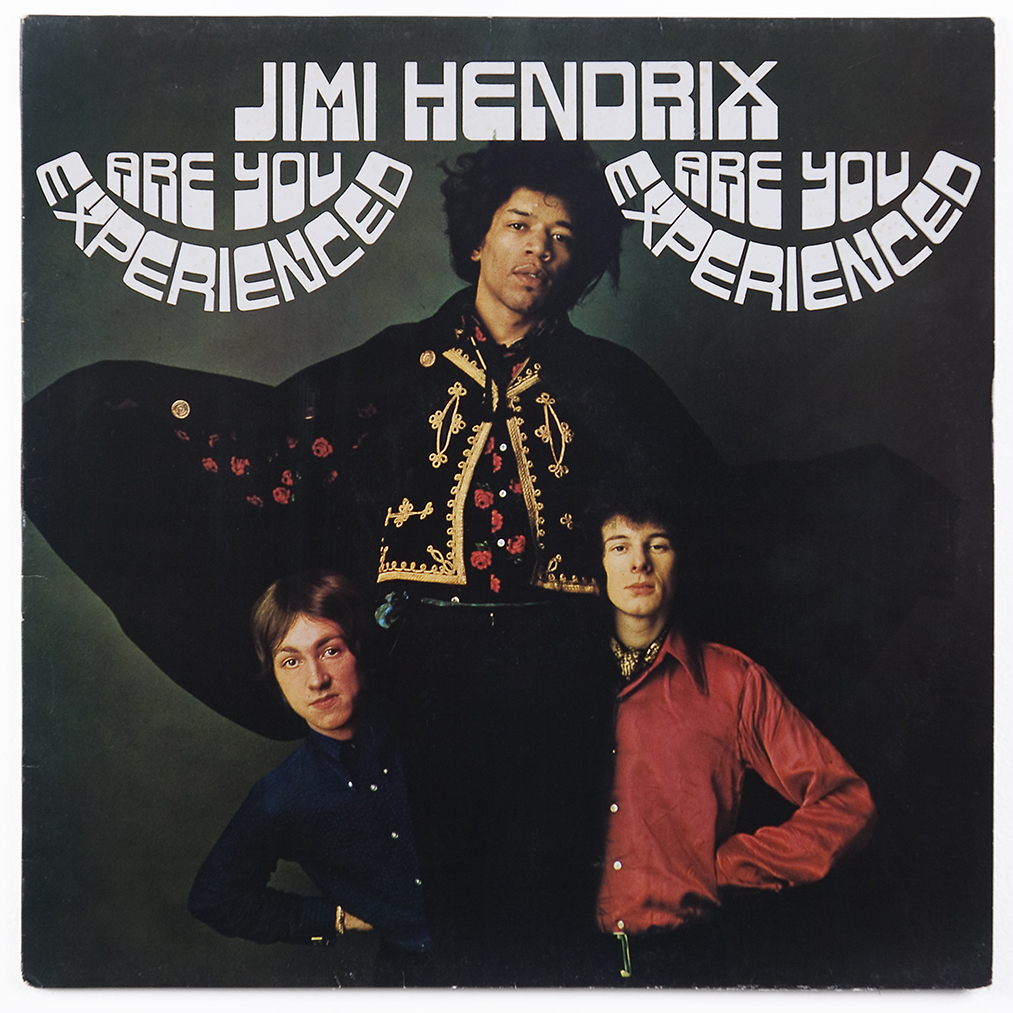

As originally designed, the album featured no group or individual name on the front cover. Instead it featured a colour photo of the band. Like most rock albums up to 1967, only the front was full colour (originally a pasted slick) while the rest of the cover was monochrome. Hendrix himself looms like a winged totem over the lower, earthbound, supporting figures of Mitch Mitchell and Noel Redding, with his raised cape mimicked by the typography of the repeated album titles, warped into lunettes. The title is crucially lacking the question mark which would have made it an interrogation, or implied an element of uncertainty. Instead it tells us, in a sly way, that we ‘are experienced’.

For Benjamin, his concern with the quality of experience, as opposed to the quality of existence, derived from his studies in the criticism of art and literature. He was pre-occupied with the fact that we only know “cultural artifacts” at a remove. While traditional critics and art historians obsessed over the original significance of things for their creators and first privileged recipients, Benjamin was the first to make our ‘removal’ from the creation of an artefact into a virtue—a path to new knowledge. As he puts it in the sixteenth of his Theses on the Philosophy of History: “Historicism gives the ‘eternal’ image of the past; historical materialism supplies a unique experience with the past”.1

His category of experience was intended to de-laminate the work, to dissolve it in an acid of time and uncover its meaning for us. This is at the heart of his magisterial later studies, of the Paris of the nineteenth century in general, and Baudelaire in particular. He was striving not to explicate what these things meant in themselves, but what they mean to us, at the point of their reception.

This he termed their real ‘origin’, in which the audience also participates. This radical concept of ‘origin’ is the key to Benjamin’s valuation of subjective experience by actual people in a specific historical context. This was later to become a key tenet of the discount usability approach to UX testing. The one and only ‘gold standard’ for whether a given product is fit for purpose remains whether or not a sample of its actual intended users can use it in a real context of intended use. The original intentions of the designer with regard to the use of the product, no matter how well-thought-out, are rendered immaterial. This applies with even more thorough-going rigour in the case of interface design—as for instance in web sites. In this case the cognitive psychology of actual individuals trumps everything—if most users cannot see and correctly interpret an on-screen artefact, it effectively isn’t there.

I’m inclined to believe that on some level Mike Jeffery, Hendrix’s business manager, understood all this when he dubbed the group, the Jimi Hendrix Experience. Because what you get is not in any real sense, Hendrix himself—he remains a quietly-spoken enigma, an extra in his own legend—we get something quite other, an experience of Hendrix. And this is consummately communicated by the design of the album cover. While Bob Dylan’s early albums promised an intimate encounter with the artist, who was pictured looking quite ordinary, a bloke you could easily meet—holding a guitar, walking in the street. Dylan’s early records show us first one side of him, and then another. Hendrix, on the contrary is presented as a totem, or a fetish—as a three-headed Cerberus, not as a real person—and his name, which is immaterial, is omitted from the cover in preference for a statement about perception, which is directed at the viewer.

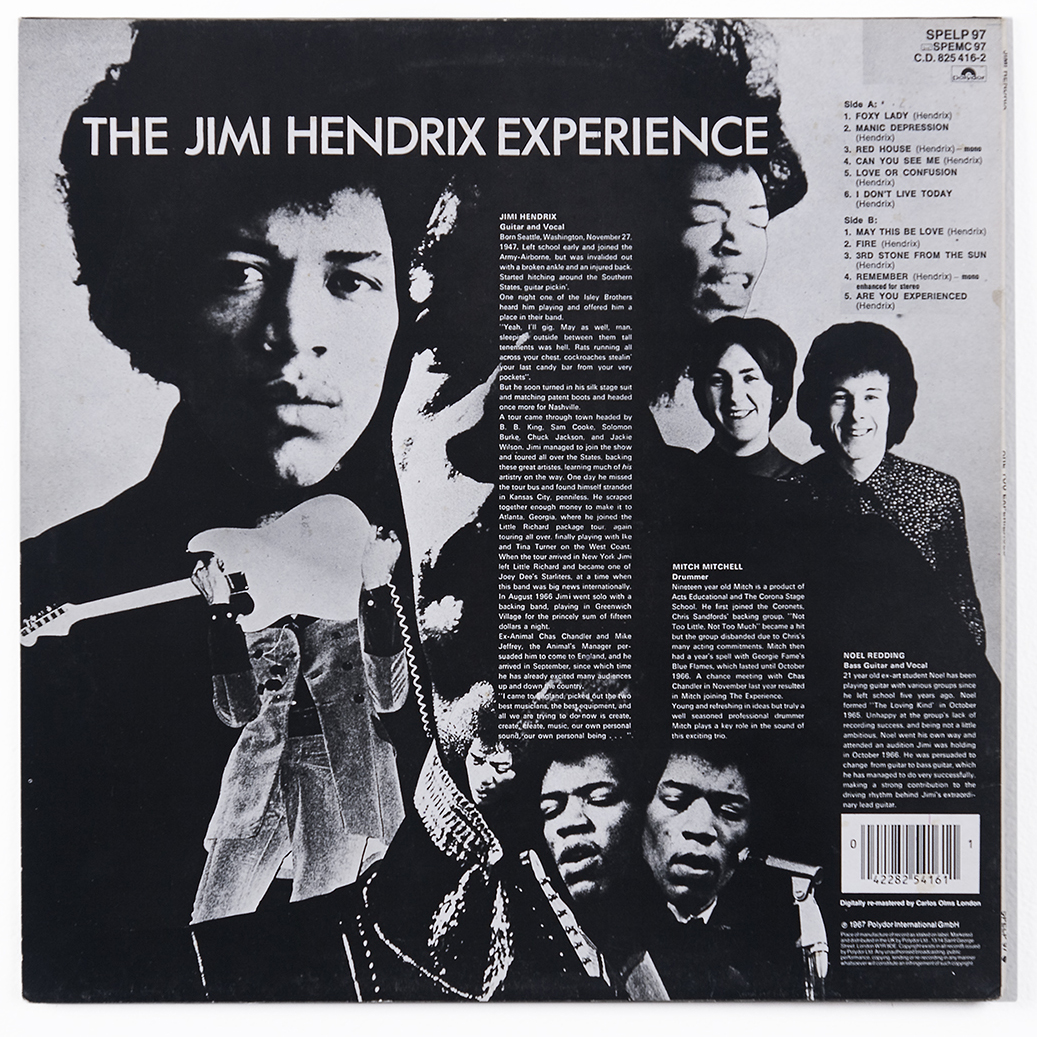

This album cover is a mirror, which reflects your gaze back—until you flip it over. Then you are presented with a visual metaphor of our second-hand experience of reality, and we discover that it is not about ‘Jimi Hendrix’ (whatever he is)—it is about our ‘experience’ of Hendrix.

On that back cover, we find that the mirror presented on the front is in fact broken. The black and white imagery on the back cover features no less than seven Hendrixes: avatars or facets of Hendrix. The pictures are sliced up, overlaid, repeated (there is another Cerberus at the bottom, this time all the heads are Jimi’s)—there’s no mistaking the message (before we’ve even heard what’s in the grooves) that this album is presenting the opposite of a faux-naturalistic picture of the artist as a young man.

Are You Experienced foregrounds that fact that we are constructing our own image of Jimi Hendrix, inside our minds. We are respond-ing to the external stimuli of sound and vision, but we are confronted not by Jimi Hendrix (the quietly-spoken extra in his own deification), but rather with a stereoscopic panoptical commodified View-Master portrait of an artist as magician/Adonis/warrior/priest. Hendrix himself goes on to explain, when we get to the actual record, that he ‘don’t live today’—and to state, not question, ‘can you see me’ (note the omitted question-mark again).

Well, yes, and no, Jimi.

The Jimi we experience is not at all as he may have intended, or seen himself, a fact that he may have come to appreciate as his short career progressed, but which it is clear his management understood from the get-go. In this he is very reminiscent of the figure of Charles Baudelaire in Benjamin’s projected but incomplete study, one of the fragmentary literary mirror-texts that fell out of the endless labour that we know as the Arcades Project. Baudelaire had no concept of himself as the first and most archetypal ‘modern man’. He thought he was a lyric poet and literary symbolist, while Benjamin applied the principles of psychoanalysis and historical materialism together to demonstrate that what he was really showing was the reification, the eternal return and the profound ennui at the heart of our experience of capitalism.

Benjamin’s Baudelaire was the precursor of both surrealism and psychogeography, and his whole argument is devoted to dismantling everything Baudelaire and his contemporaries believed about his work in favour of a re-reading from the point of view of an anti-fascist refugee haunting the libraries of Paris, in the shadow of the gas chamber chimneys.

By 1970 Jimi had come to understand that he too, as a commodity, was living in a room full of mirrors. This is a place in which communication depends on the reception of coded messages conditioned by economic realities, and does not even approximate the direct privileged communication of the prophet, to which Jimi aspired. He was not to be the angelic harbinger of the Messiah, whom Benjamin saw at the end of history, staring back at the wreckage. Jimi wasn’t what he thought he was at all, and he couldn’t control the process of his own becoming. In a sense he could be anything he wanted, except the thing he actually aspired to be. This devastating epiphany was the literal realisation of the fractured personality depicted on the back cover of his first record, with which Jimi found himself unable to reconcile.

Our position is as the interpreters of a reality even more radically mediated than that encount-ered by Jimi, or his contemporary Guy Debord—whose The Society Of The Spectacle came to light in the same year as Are You Experienced—or by Walter Benjamin, whose understanding of these experiential conundrums was sharpened by his backwards-telescoping of the nineteenth century from the perspective of the twentieth. And as a professional critic of ideologically-conditioned communication tools such as corporate web sites and transactional interfaces, it behoves me in particular to bear in mind that experience is the primary category of all knowledge, just as “the analysis of ‘fame’ is… the foundation of history in general”.2

For me Jimi—like Baudelaire, or Kafka or Aragon for Benjamin—is a symbol of both the unknowability of the past, but also its potential mutability. All cultural products can be recast in the light of our specific historical standpoint, our experience with the past. It is this heroic potential, visible in “the brokenness of the sensuous”,3 which Benjamin also perceived in Baroque allegory, that hysterical effusion of images and meanings that prefigured the end of meaning in the totalitar-ianism of the commodity. Capitalism’s “immense accumulation of spectacles”4 is “precisely what Baroque allegory, beneath its mad pomp proclaims with unprecedented force… the problematic of art”.5

This inherent lack of freedom, embodied in the reality-warping potential of commodified experience, is the mountain which Hendrix promised to “chop… down with the edge of my hand”. This is a dharma-trampling feat we must all emulate one way or another—in order that we might really ‘live today’.

Footnotes

Walter Benjamin, Illuminations: Essays and Reflections. New York: Schocken, 1968. p.262. ↵

Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 1999. p.460. ↵

Walter Benjamin, ‘The Antinomies Of Allegorical Exegesis’, in The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility and Other Writings on Media. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2008. p.177. ↵

Guy Debord, The Society of the Spectacle. New York: Zone Books. 1995. p.12. ↵

Walter Benjamin, ‘The Antinomies of Allegorical Exegesis’. p.177. ↵