Reasonable Precedents – Luke Wood, Noel Waite

Hi Noel, I’ve been buggering about all day with various false starts to this ‘interview’ idea, all of which got too complicated, muddy and elaborate. After today’s attempts I do now have some clearer ideas about why I wanted to do this and what I wanted to ask, but I’ll try to start very simply (cleanly) here and then we can get carried away or lost in the quicksand later on.

History obviously has a fundamental role to play in the way a discipline or a practice is perceived, and so to begin with I’d like to ask what you think about the ways in which local history specifically has (or has not) informed an understanding of graphic design in New Zealand?

Before addressing your question, it might be useful to examine your assertion that design history is fundamental to the discipline and practice of design, as I think it is important to distinguish between what history brings to the discipline and to the practice of design. Herbert Simon’s The Sciences of the Artificial was a landmark book in that a Nobel Prize-winning economist recognised the significance of design in understanding the artificial world we inhabit. His assertion of the necessity for a discipline of design with “subject matter that is intellectually tough, analytic, formalisable and teachable” can be seen as external confirmation of efforts within the design community at that time to better articulate design methodology and theory. History, criticism and theory are the necessary components of a rigorous discipline in that they provide evolving explanations of the past, present and future of design. I would argue that history is a foundation discipline in that, once the facts have been established, we can critic-ally evaluate past successes and failures and put forward theories to explain how design operates in particular social and historical contexts. Or as Etienne Gilson put it “History is the only laboratory we have in which to test the consequences of thought.” With the historian’s advantage of hindsight, this should provide some understanding of how design has evolved to the present day.

Practice is primarily concerned with designing for present needs and desires, and while designers may look to the past for inspiration or ideas, in the process of designing, they must be either insightful cultural analysts, trust to foresight or apply new theories if they are to create something genuinely innovative. It is in the application of foresight that I think design history has direct application to practice. Through scenario building, designers can develop future scenarios as experimental test beds for their ideas. To ensure that these scenarios are plausible, it is necessary to research historical information to identify present trends. This has the advantage of broadening designers’ knowledge of design and understanding of their own practice by considering the contexts and implications of past designs and providing quality benchmarks for designs that have stood the test of time. At its most fundamental level, it also prevents designers reinventing the wheel, or the poster perhaps in the case of graphic design.

If we accept that design history is one of the fundamental constituents of a discipline of design, then the problem we face in New Zealand is that the major constituents of a national history are largely unpublished. As we have discussed, they remain in archives, public and private collections and in the heads of senior practitioners. As regards archives, the fundamental problem is one of definition: design covers a wide range of subjects and does not fit naturally within established categories either within museum or library classifications. After a recent visit to several museums around the country, the predominant curatorial perception of design is one of applied arts. This narrow definition tends to exclude products of industrial and agricultural manufacture and anonymous or collective design. Such New Zealand design exists, but records may be buried within larger company or industry archives. In the nineteenth century, these tended to have a regional basis, and there are many originary claims by manufacturers that need verification in a national and international context. In terms of graphic design, the printing industry and the history of photography and advertising are under-researched, although there is some useful work in the field of bibliography.

This has been complicated by the dominance of art and architectural history framing the discourse around design, and an over-emphasis on stylistic analysis with a particular focus on modernism and cultural nationalism. Douglas Lloyd Jenkins’ contributions are an example of this, although his book At Home: A Century of New Zealand Design remains the best attempt at a national design/architectural history to date. Ann Calhoun’s The Arts & Crafts Movement in New Zealand, 1870–1940: Women Make Their Mark offers a complementary reading with more relevance to graphic design history.

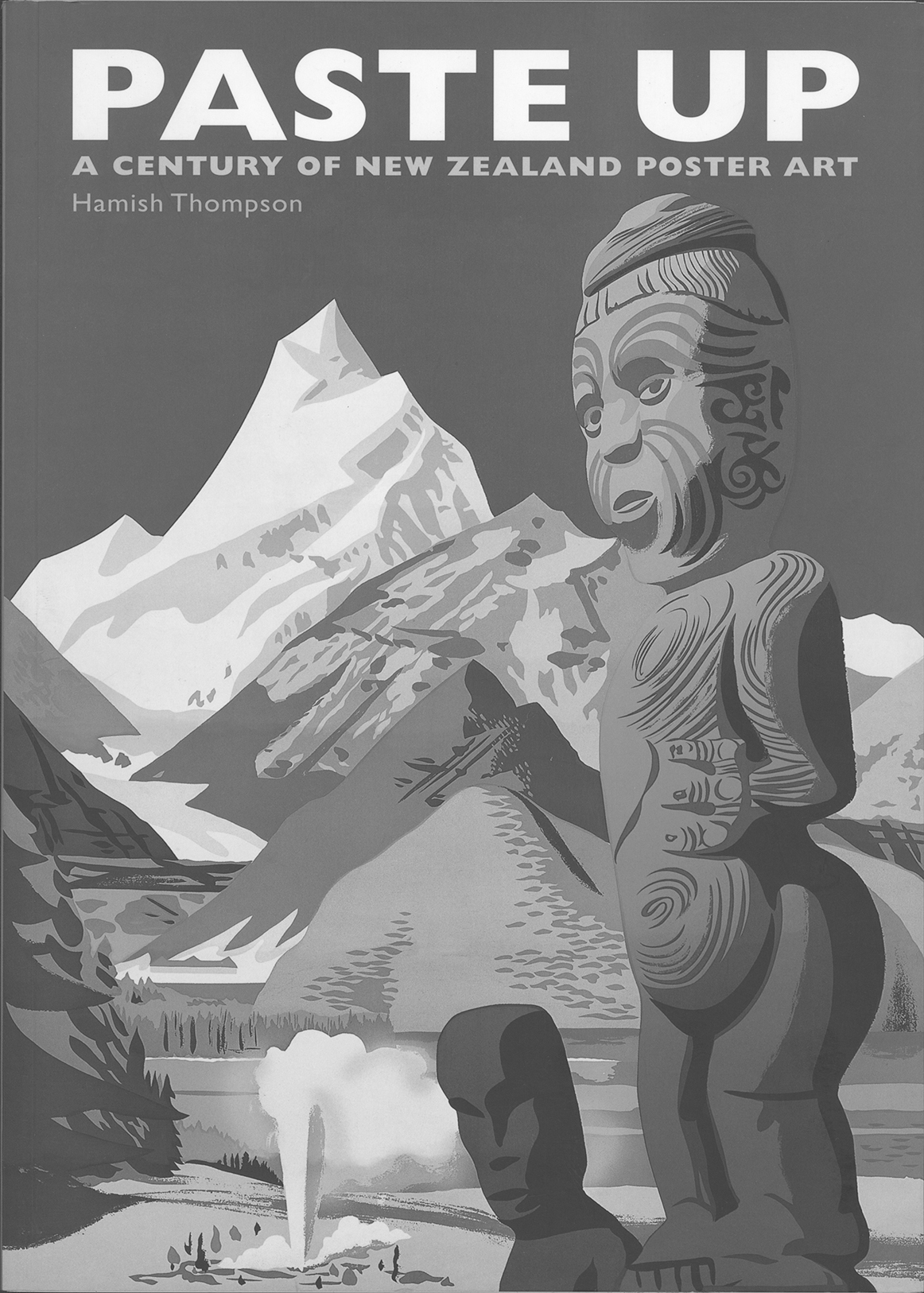

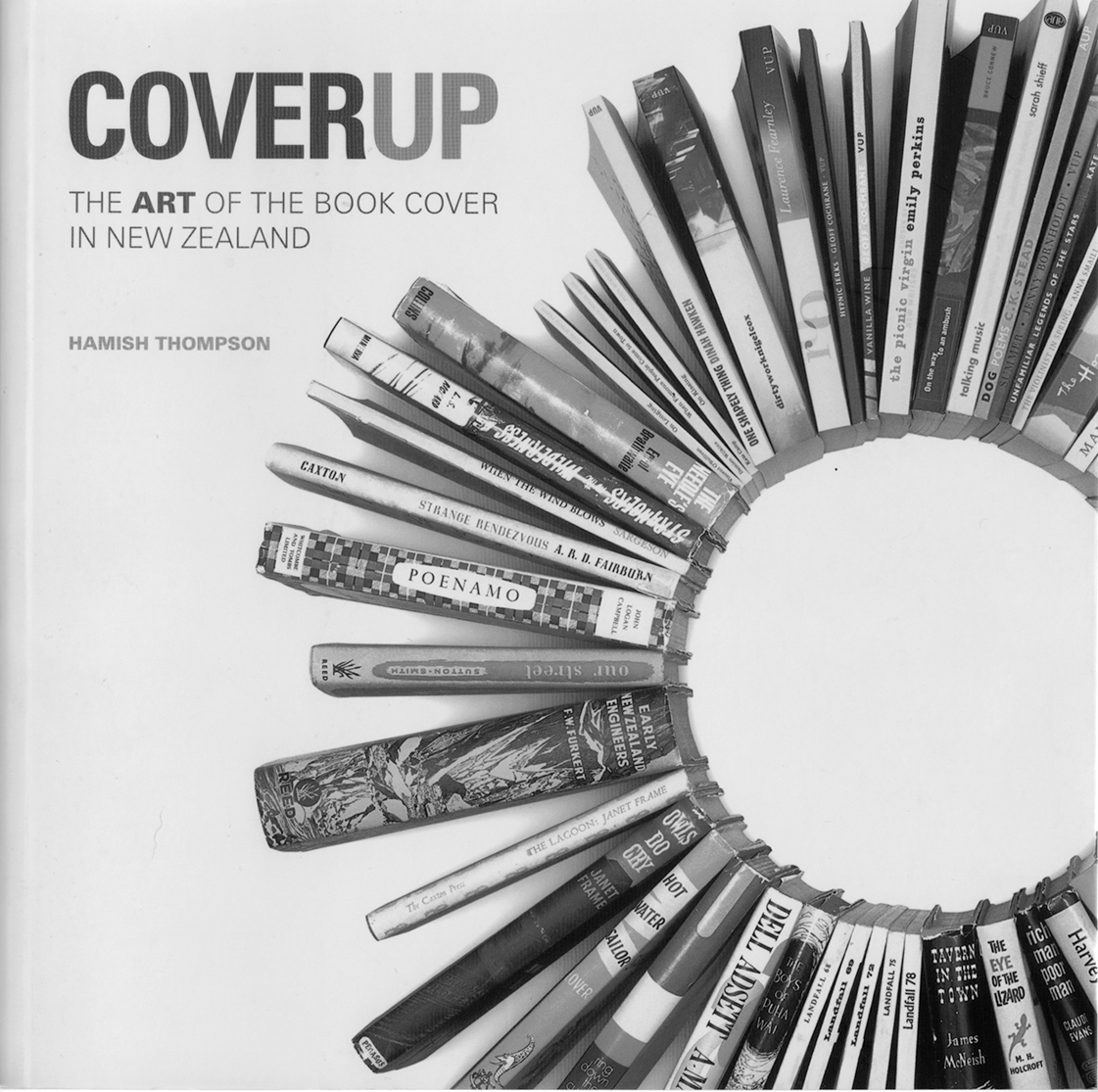

In terms of practice, Hamish Thompson deserves praise for making more widely known New Zealand book and poster design, and these have proved excellent resources for practicing designers, and I am aware of one major contemporary branding campaign that drew on analysis of the material presented in his books.

by Hamish Thompson

Godwit, 2003

by Hamish Thompson

Godwit, 2007

With the wider availability of such texts, the next phase would be some more wide-ranging critical analysis of New Zealand graphic design and comparison with international practice. Here again, there is a further complication of what Victor Margolin refers to as “the politics of the artificial.” The increasing professionalisation of design, particularly industrial design, in New Zealand and Labour government initiatives to support design for primarily economic ends through Better by Design have resulted in a narrow conception of design focused on products.

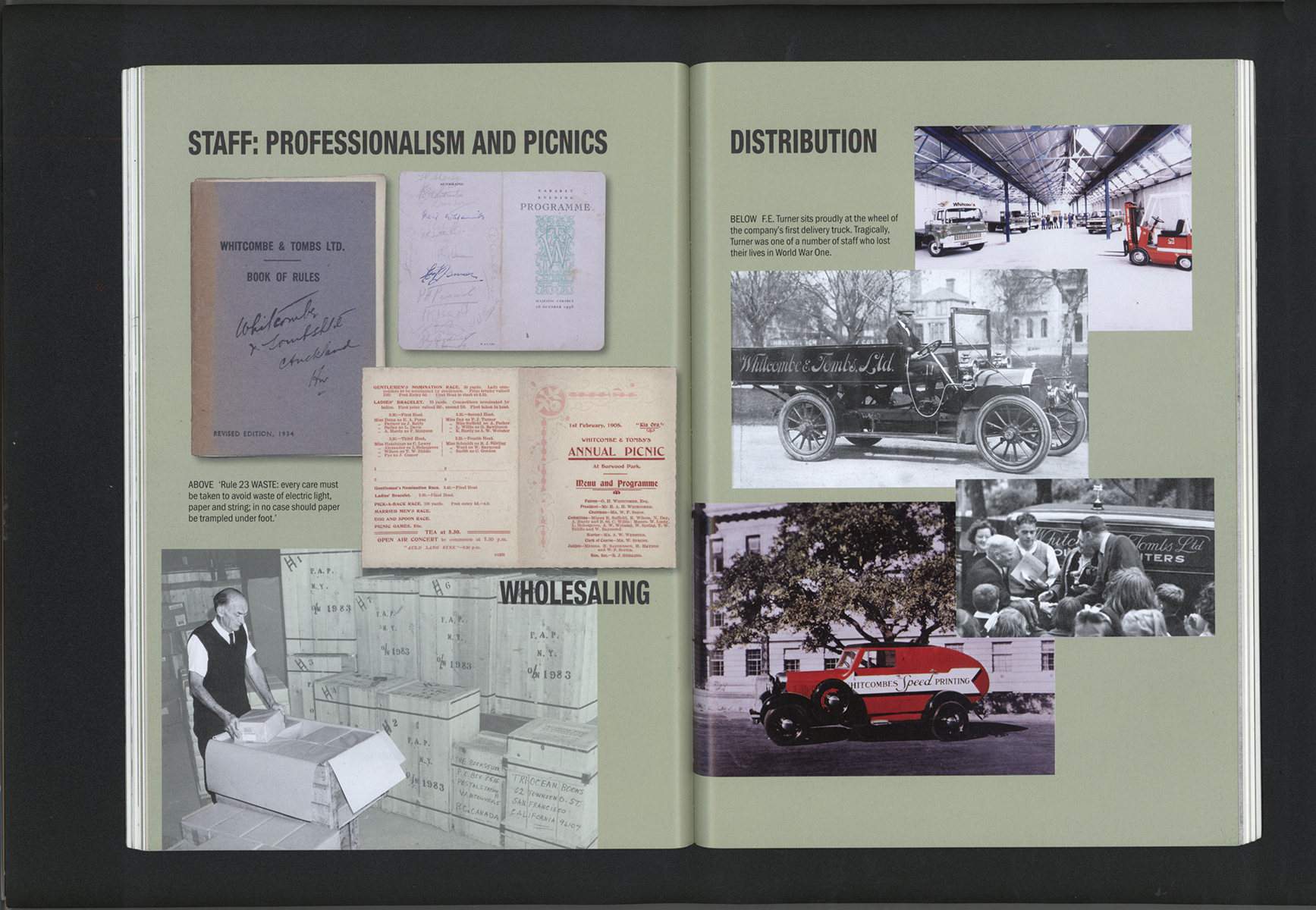

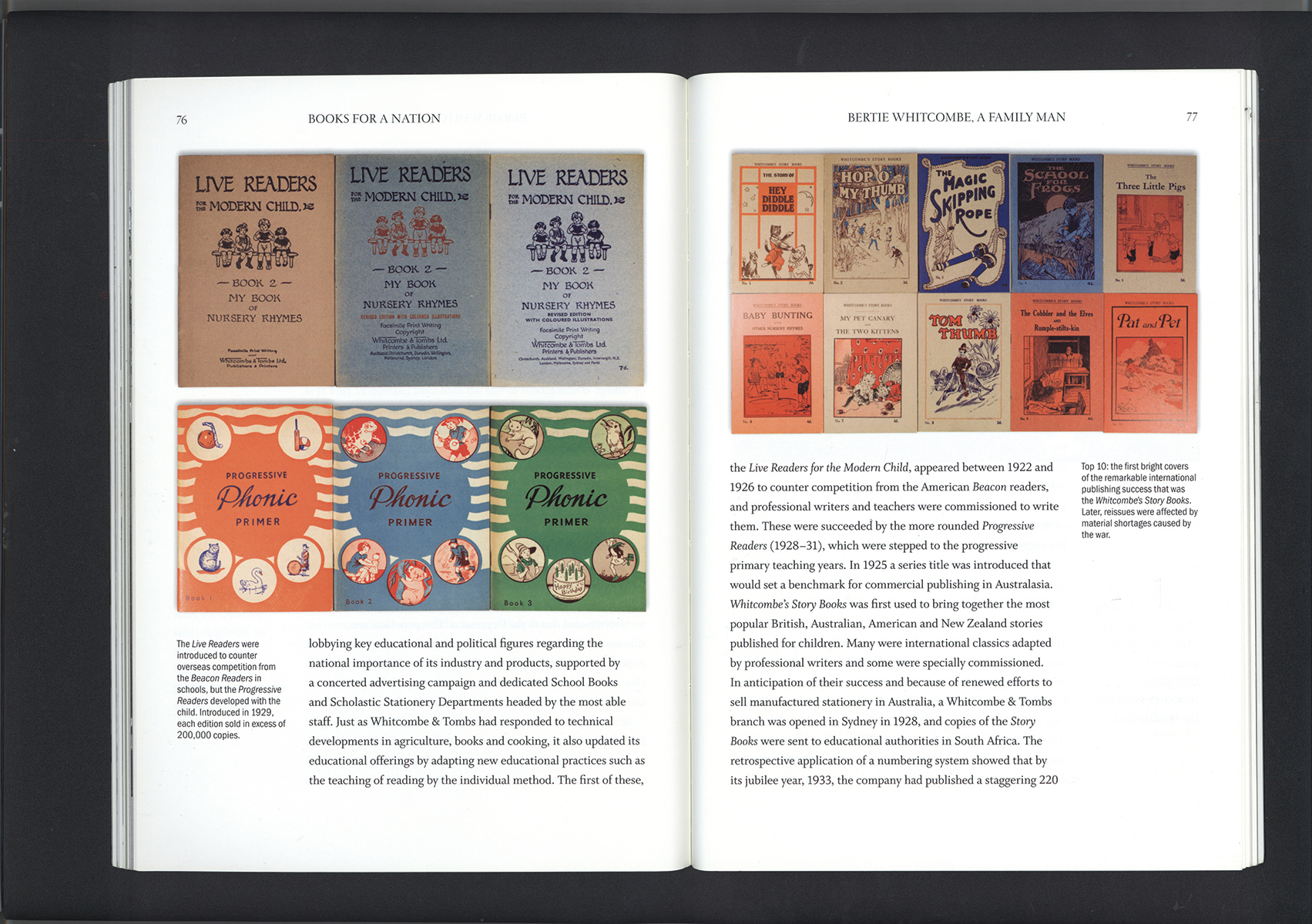

A quick scan of the Better by Design website gives little indication of an active culture of communication design, with Selwyn Feary of Shift being the exception that proves the rule. International comparisons are frequently made to countries such as Finland, which has a long tradition of craft design linked to strong industrial foundations, and little attention has been devoted to successful historical precedents in New Zealand. These fall into the agricultural and wider scientific communication sectors, and with more direct reference to graphic design, the printing and publishing industries. Professional New Zealand book design in particular stands international comparison and has a record of international success dating back to the beginning of the twentieth century. It can be argued that the legacy of Whitcombe & Tombs’ educational books for children can be seen in contemporary successes such as Wendy Pye and Learning Media, as well as a rich range of small-scale niche publishers and related design companies.

Finally, there is the cultural contribution to our visual environment within New Zealand, and international perceptions of New Zealand that flow from it and from international communication strategies in marketing, tourism and art. Graphic design also has a critical role to play in challenging dominant commercial and political discourse, and providing alternative ways of looking at our society in the present and future. The rhetoric of the present government admits a role for design in maintaining and developing cultural identity, but again there is little published evidence to support it. The role of Maori craft practices, iconography and tikanga also deserves much deeper consideration given their importance to past and present graphic representations and communication of New Zealand.

So, in short answer to your question, the discipline of design in New Zealand has not been well served by local history and this has flowed into political perceptions about the evolution of design here. At the present time, the situation faced by design historians is similar to that faced by New Zealand historians in the 1970s: there is a considerable body of fundamental research that needs to be undertaken, critically evaluated and communicated through teaching and publication. In recent years, practitioners have been better served by local history, but there is still plenty of work to be done to give a more complete picture of the evolution of graphic design, critical analyses of its successes and failures, and future potential.

As that was a fairly long-winded answer, could I now ask you whether you regard a knowledge of New Zealand graphic design history to be of value to you as a design practitioner, and as an educator, in the face of increasing globalisation?

Well that's the thing, I don’t think I have a good knowledge of NZ graphic design history, so it’s hard to say. I’m not sure that my growing interest in finding out about certain local precedents is so much to do with any sort of anxiety about globalisation though, but more about simply seeing how people here, in this particular situation, have made things work (or not). Your introducing me to Robert Coupland Harding’s publication Typo is a good example—being able to locate ones own work within some sort of existing (more relevant?) trajectory is useful. As I’ve been finding out more this has begun to feed into conversations with students, and they certainly respond enthusiastically to that. I think students, and probably even the larger design community, tend to think the lack of local history simply points to the fact that nothing interesting ever happens here. Which I guess is what I was getting at in my initial question.

You’ve been working against that sort of attitude for a while, and have pointed out to me previously that interesting people and important projects are out there but that they are “sitting in the museums, archives, private collections and peoples heads”, and that “designers AND academics need to get amongst it.” (That’s from an email you sent me last year, which I also used in my introduction to the Typo reproductions in The National Grid #4.) Anyway, on reading your “long-winded answer” I thought about that... the getting amongst it, the finding out, and your uppercase “AND”.

It’s an exciting prospect that there’s all this stuff buried away around New Zealand just waiting to be found, but I’m wondering what a designer’s role in that might be? In our very first issue you argued for a “functional design history that establishes local precedents and encourages designers to knowingly develop or subvert them.” That makes it sound like the historian produces the raw material and then the designer sets to work with this in mind. But is that what you mean by “get amongst it”? That has the sound of getting your hands dirty about it. And that’s what I’m after here I think... how, as a designer, I might engage with that sort of initial research.

by Hamish Thompson

2003

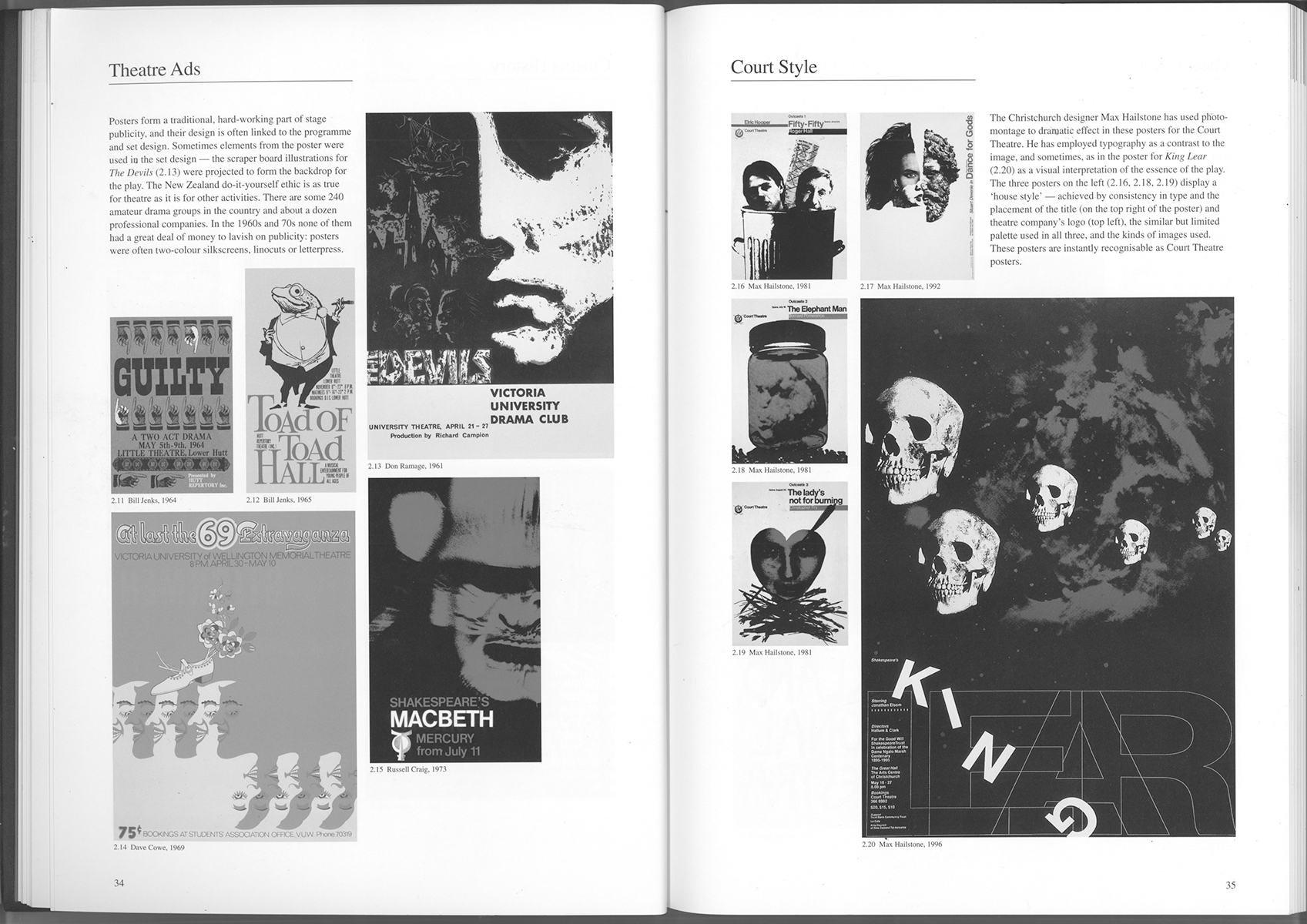

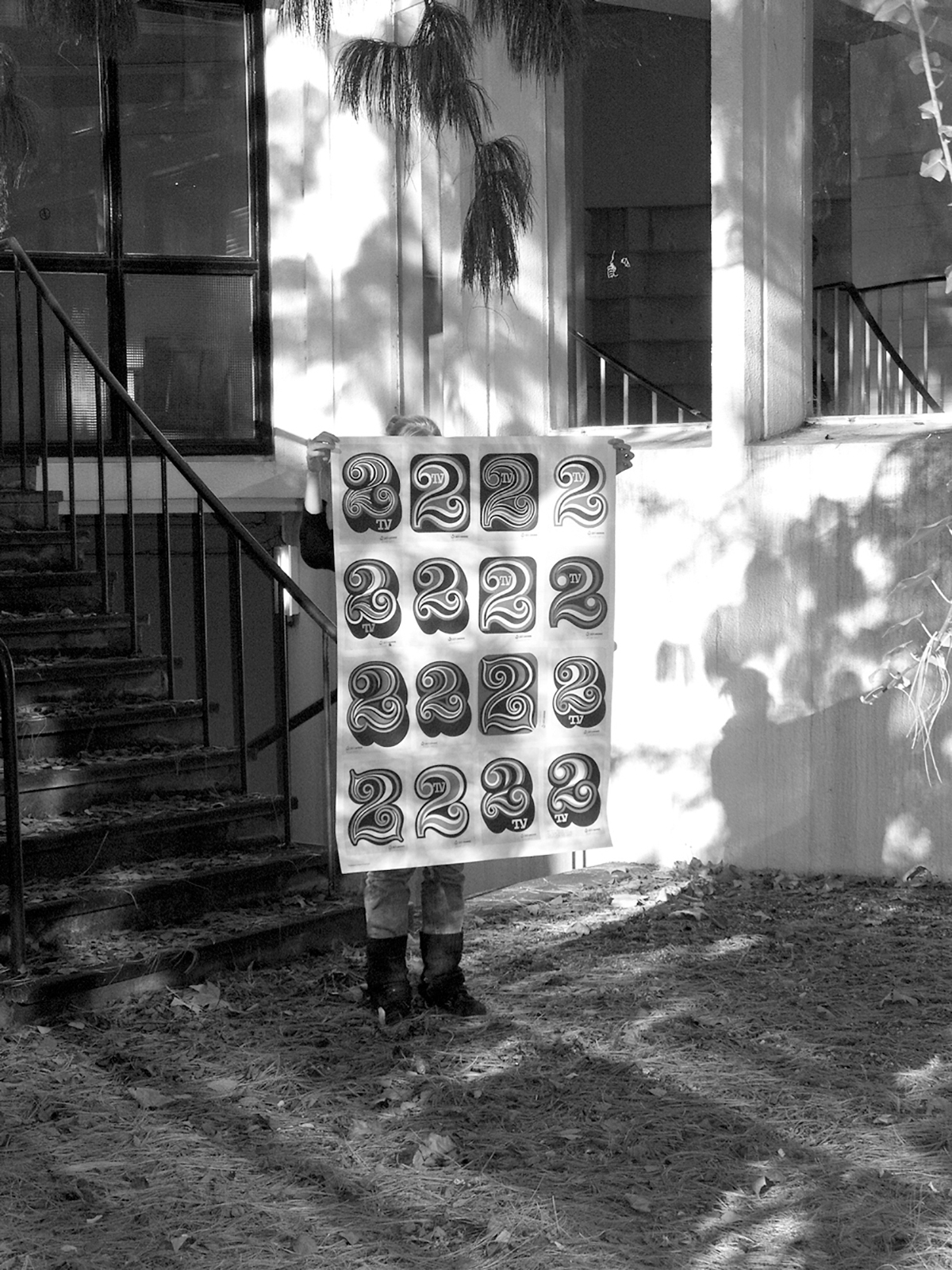

Let’s take Hamish Thompson as an example. Hamish is a graphic designer by trade who, in his research for his books you could say, works very much like a historian. On the other hand there’s something about David Bennewith’s research into Joseph Churchward that's quite different... and it’s got something to do with his approach to the research being more sort of ‘designerly’ somehow, or more akin to practice in spirit. You’ve seen his Churchward interview in our previous issues? Also check out his Suggestions Poster,1 I’d be keen to know what you think? Especially in relation to what David says on the Jan van Eyck website; “Although the material could be viewed as being biographical at the outset, through research I hope to translate it as an impetus for new work—to re-look at his designs and the possibilities in using them today.”

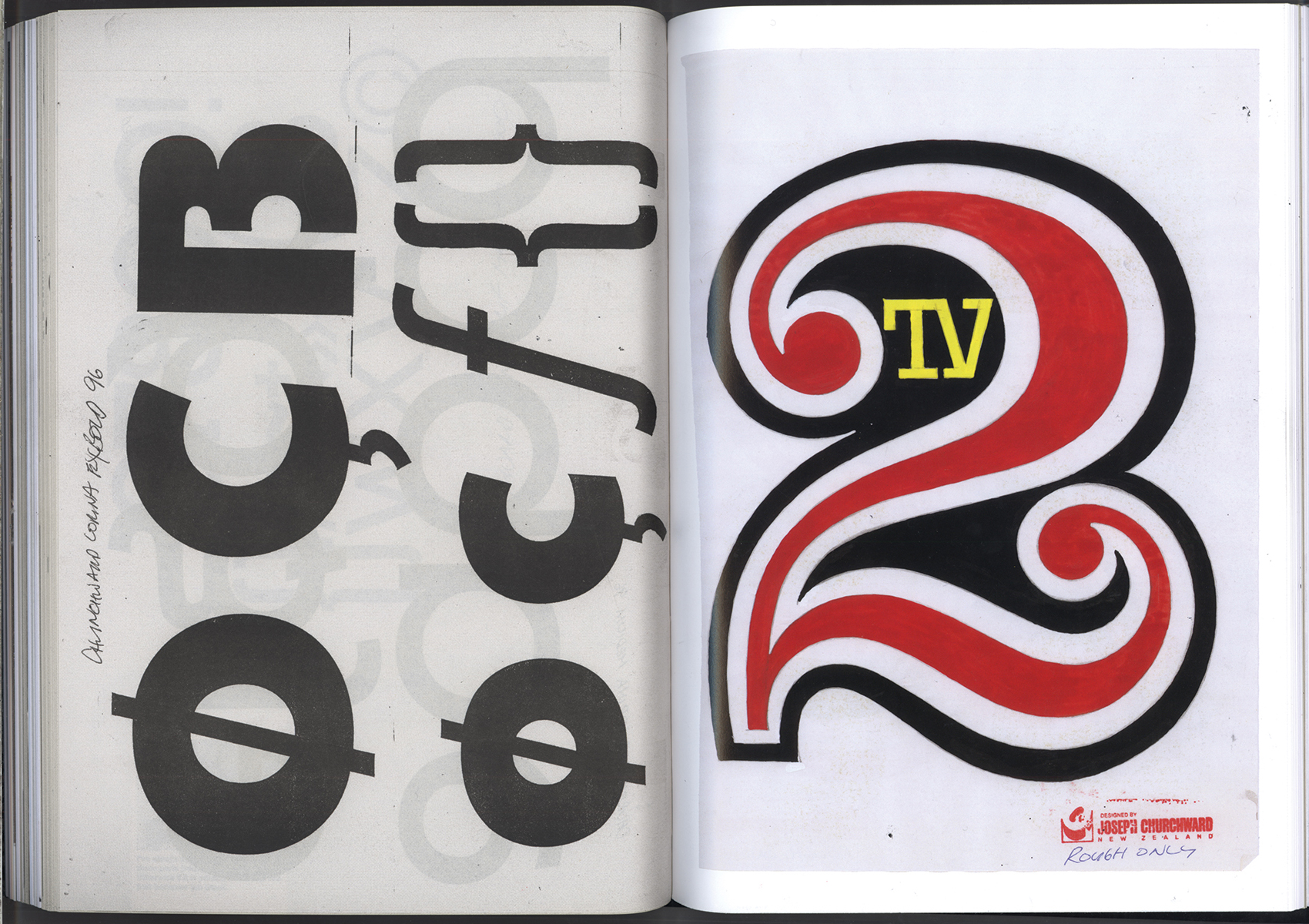

Joseph Churchward's suggested designs for TV2 logo

Poster by David Bennewith

2007

Perhaps I’m not explaining myself very well, but do you know what I mean? I think much of this is the result of the anxiety I felt about reproducing those pages from Typo in our last issue—talking to you, and with Sydney Shep too, I felt a bit like I was trespassing or something? I became very aware that there’s a framework and certain protocols that exist, and that I was, no doubt, making all sorts of faux pas in my initial excitement to do something with this stuff.

Ok, I think we share the same motivations for this work in that the absence of an accessible New Zealand design history results in a perception that “nothing interesting ever happens here.” From our own research, we know this to be demonstrably false. Because we are both also educators, we feel a responsibility to correct this misapprehension. This was brought home to me when one of my students went on an exchange to Argentina and enrolled in a design history course to find out about the fascinating history of design in that country. Instead she received a canonical history of industrial design beginning with the 1851 Great Exhibition in London! Now, having given similar lectures, I know that these are easier to prepare than the ones I give on New Zealand design history because of the wealth of primary and secondary sources I can draw from.

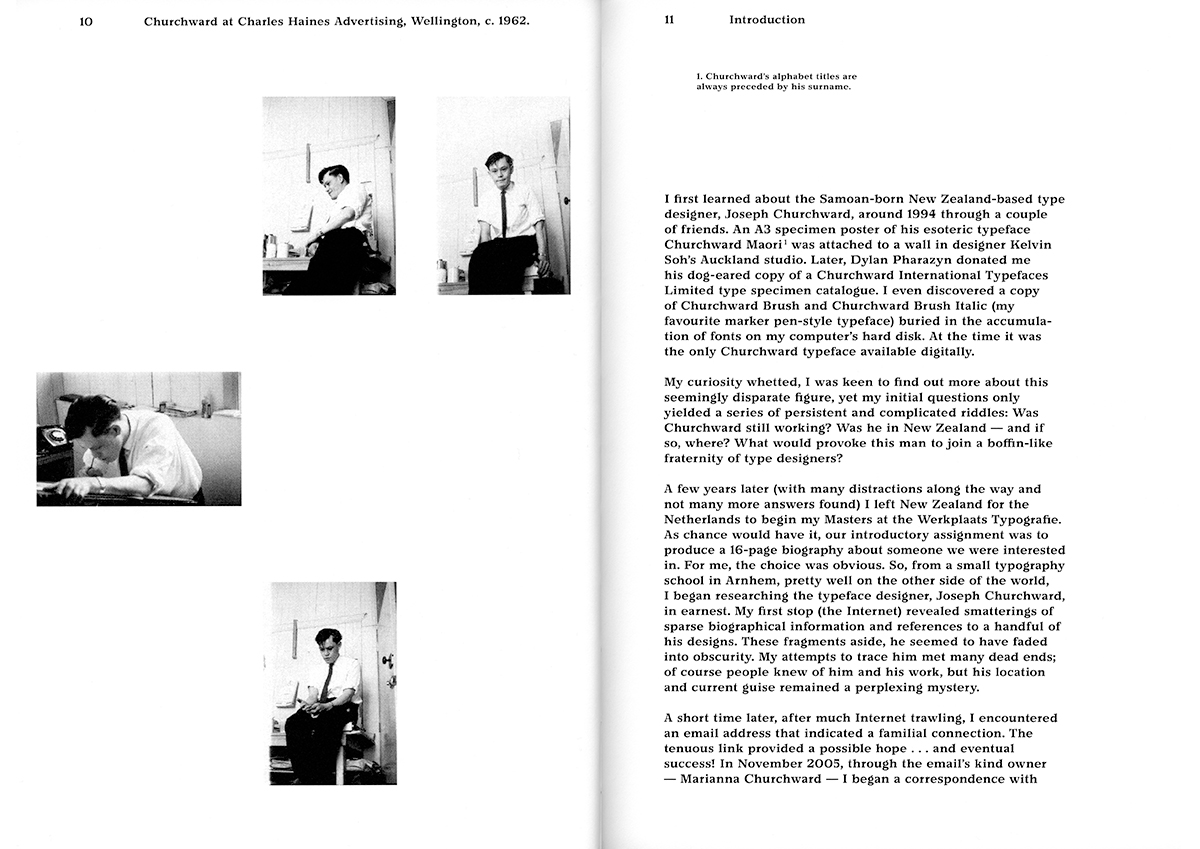

So, the next question you pose is the important one of how do we go about doing this kind of research, and you draw an interesting distinction between the work of Hamish Thompson and David Bennewith. Both worked with primary resources, which according to the American Library Association (ALA) definition “are original records created at the time historical events occurred or well after events in the form of memoirs and oral histories”.

In Hamish’s case that involved working in archives and libraries selecting representative posters and book covers for compilation in commercially published books. David essentially conducted an oral history with Joseph Churchward which was reproduced in The National Grid #3 and #4 with photographic illustration. Both are now great secondary resources to have.

Both also involved designing, as I know that Hamish was intimately involved in the design of his books, although they were mediated by the requirements of a commercial publisher. So, in this sense, I think both were ‘designerly.’ However, the design outcomes clearly serve different purposes, with Hamish’s being primarily historical while David’s posters are primarily about the design process and pay homage to Joseph Churchward’s example. There’s clearly been something interesting enough going on ‘here’ for David to pursue it over there in Holland—and the same could be said for your work with the McCahon typeface.

However, there’s still something niggling me about a ‘designerly’ approach to (historical) research that I haven’t really come to grips with yet. Historians have a tendency to privilege words over images, as they are supposedly more reliable and less open to interpretation. Images, particularly photographs, are often used in a subsidiary role to illustrate the text. This was clearly not the case with Hamish’s books or David’s interview, and David makes it more explicit when he defines his research as involving ‘re-looking’ at Churchward’s designs. By contrast, my article on Alan Loney began with the text and, after discussion with you, involved a considerable amount of re-looking at his book designs. I hope the result, while still primarily biographical and historical, provides more insight into his craft design process. The photographs I took of the book stacks were a deliberate attempt to show a different private press direction in his design. Because this shift came late in the process, we were constrained with black-and-white reproduction and the important aspect of Loney’s use of colour isn’t evident, which I know you regretted. However, as these books are mostly publicly available in libraries I was less worried as the article may hopefully encourage people to have a look for themselves—a different tack on the relationship of primary/secondary materials.

by Noel Waite

Whitcoulls, 2007

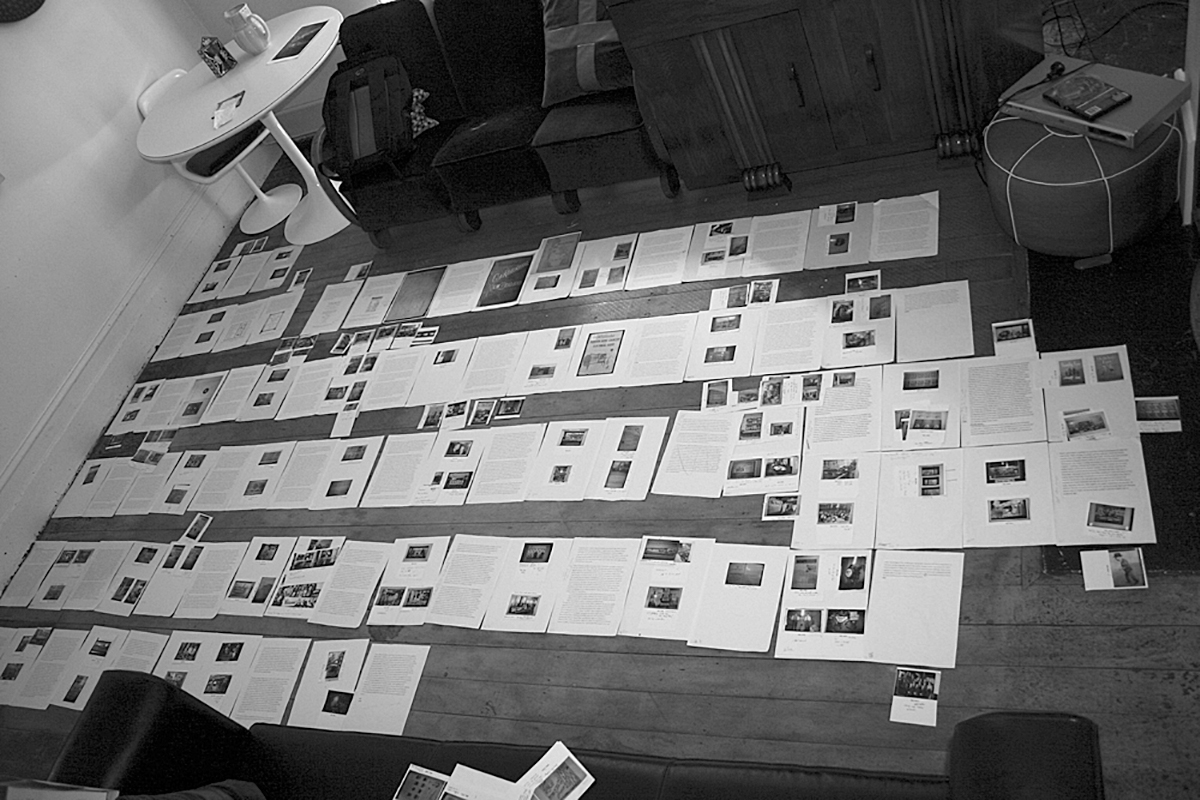

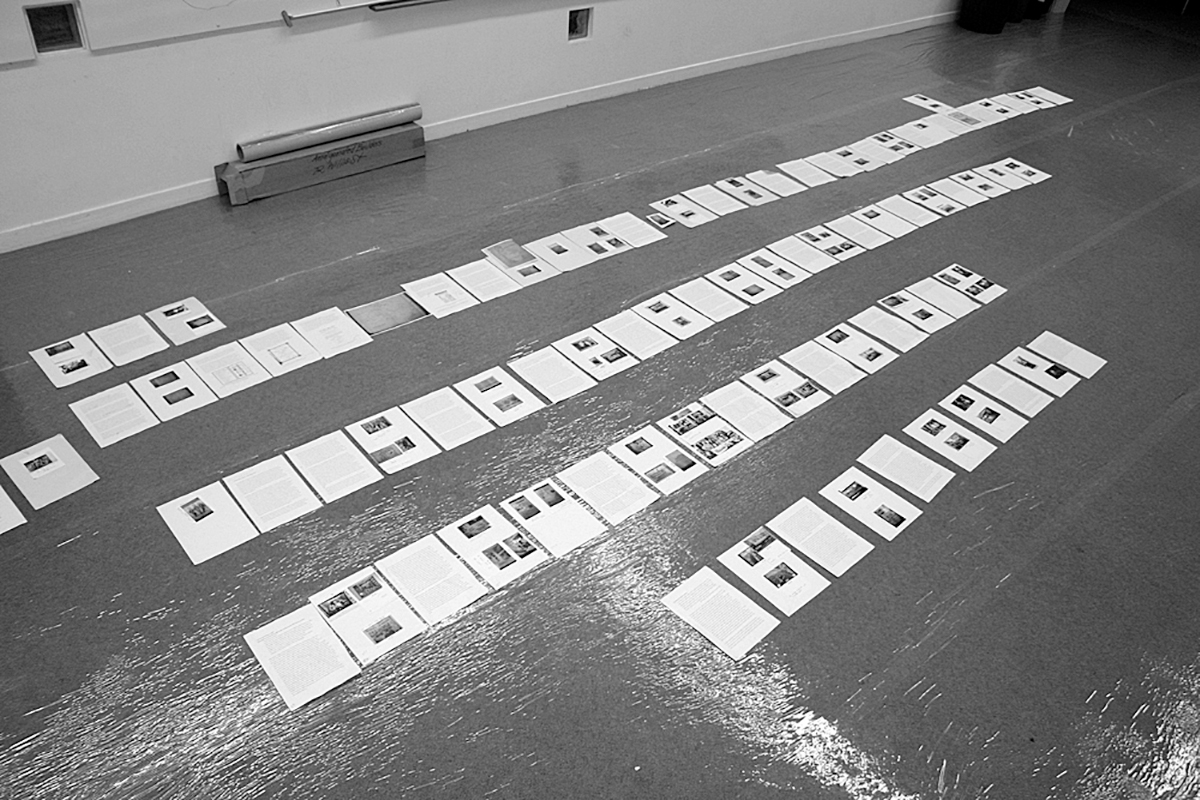

I also came up against this in my recently completed history of Whitcombe & Tombs/Whitcoulls. I had done the research and then looked at precedents of New Zealand company histories in the local public library—and immediately had a crisis of confidence! They were uniformly poorly designed with little graphic content. This led me to reconsider my process and to re-examine the (over) 700 photographs I had taken. I recomposed the book by old school cut-and-paste on the floor in order to achieve a more integrated approach and reconfigured the brief as ‘A commemorative story about the past, present & possible futures of Whitcombe & Tombs/Whitcoulls that is as simple as a children’s book.’ This made reference to the success of the company’s highly successful illustrated children’s books in the 1920s. As a result of these experiences I will pay more attention to graphic research from the beginning of the process in future. This is clearly relevant to teaching and practice, as much in design history as graphic design.

Noel Waite's photographs of his working method for his history of Whitcombe & Tombs/Whitcoulls.

The ALA definition goes on to say: “These [primary] sources serve as the raw material to interpret the past, and when they are used along with previous interpretations by historians, they provide the resources necessary for historical research.” Douglas Lloyd Jenkins’ book At Home is a good example of this synthetic approach (drawing on both primary and secondary sources) to examine domestic design and craft in the context of architectural history. Because of his focus on architectural design and the implicit value of connoisseurship associated with his stylistic approach, its contribution to understanding how people design is less evident. Ultimately though, historical and design research should be seen as complementary and should draw on the skills of their respective practitioners, and I think we’re the richer for all their contributions. The designers in us are possibly most happy when we see the ideas we have tried to communicate applied in new situations, but that does not detract from the value of historical interpretation.

by Noel Waite

Whitcoulls, 2007

Finally, in regard to the anxiety of trespass, I felt the same thing when I gave my first design paper about the typography of the New Zealand modernist Group Architects manifesto——on a panel with two architectural historians. I was terrified about making assumptions or mistakes about architecture, but as it turned out they showed a great deal of interest, appreciated the different perspective and directed me to some valuable architectural sources. This free exchange of ideas is how the academic community is meant to function, and differs from the professional community in this regard which is more constrained by commercial imperatives. However, while its disciplinary structure provides useful defining limits to specialist fields of knowledge, it can discourage cross-disciplinary inquiry. As we discussed earlier design is an emergent discipline that is pluralistic in outlook, drawing willingly on relevant theories, methods and ideas from other disciplines, and integrative in practice. The value of inter- or cross-disciplinary research is being increasingly recognised in both theory and practice, and the key is to take account of specialist disciplinary expertise and insights and, in return, take every opportunity to communicate what design might offer these other disciplines.

Does the type of ‘designerly’ or graphic research I am trying to articulate have any resonance with your own experience as a graphic designer or as an educator? Also does it matter if students and practitioners only see reproductions of primary work such as Railway Studio posters or Churchward’s fonts, or do you see additional value in them seeing the material firsthand?

I like to think a reproduction has a different sort of value that runs parallel to the real thing. This is mostly to do with distribution—the ability of the reproduction to travel further and more widely than the original. As students in New Zealand our understanding of art and design is generally built from reproductions in books. I had the strange experience of falling so in love with those books that I actually felt slightly deflated when I eventually travelled overseas and saw certain things, paintings mostly, ‘in the flesh’. Perhaps there’s a danger there where the reproduction is your first point of contact and by the time you get around to seeing the real thing the power is lost somehow? This isn’t always true. If I have a CD re-release of an album I like and I find it on vinyl I’ll buy it every time, mostly for the big 12" cover. There’s definitely a spirit the artefact has that an image of it can never represent—the material, its weight, exact colour, subtleties of over-printing etc, but I think it has something to do with the way time works on things too. You know how people will try and artificially age things—and it never looks right. You can’t fake that very well. The passing of time installs a sort of magic onto things.

Your initial question gets me thinking about an internship I did a few years ago at Hatch Show Print, an old letterpress printer in Nashville, Tennessee. At the time I was interested in the idea that by working backwards—messing around in the past—I might find new ways forward. Like side-roads that were missed the first time around. I’m not really talking about ‘innovation’ in the grand sense here—formal or technical advancements for the discipline/industry—but rather more simply, and selfishly, just some sort of evolution in one’s own practice. And from David’s comments I get the impression he is interested in something similar. With Hamish’s books however, I can’t shake the feeling that the books could have been designed prior to the research being done, and then the text and images just dropped in afterwards. Although knowing that Hamish is a designer in the first instance, I would assume he would have approached it in a similar way to your working on the Whitcoulls book?

Teaching a studio-based course in an art school that has a strong art history department the idea that historians and artists/designers privilege words and images differently comes up quite often. I’ve been interested to discover though that our art historians, even at postgraduate level, don’t talk about writing. I was surprised because from my position that would appear to be their craft? Which sort of brings me back to the chase here, and maybe what I’m after is a difference in how, depending on our craft, different disciplines go about interrogating their subjects? And perhaps at the end of the day I’m just wanting to argue for some sort of license to be able to play with history in a speculative and intuitive way? Maybe that license already exists? I was interested to know actually, given your earlier comment about creating “something genuinely innovative”, what do you think about Peter Saville’s example? He, among others, was heavily criticised by the likes of Jon Savage in the early 1980s for superficially rehashing the aesthetics of early Modernism. Yet now he is celebrated as a canonical figure. Is it pushing it to consider his early work (for Factory Records) as some sort of practice-based historical research?

You packed a lot in those three paragraphs Luke, and I didn't really know where to begin—hence the break in correspondence—not to mention all those other things like teaching, research, administration and life that intervenes! So I’ll cut to your chase (which incidentally at least one internet source suggests is a printer’s term relating to the chase of type on the press), and hopefully loop back to cover some of the other interesting points you raise. Clearly, one of the defining features of disciplines, aside from the subject matter, are the methods by which they interrogate their subjects. Take Art History, a discipline which Design History logically borrowed from in the 1960s and 1970s, when design was largely taught in art schools. At one level its craft was writing in the sense of disseminating knowledge about art and artists, but it was and is also about reproduction of unique artworks, in lecture theatres and publications, so that people could re-look at them in a considered and disciplined way. However, the necessity for this kind of close examination of an elite canon has been challenged both within Art History, and in a more pronounced way in design, where we are talking about mass-produced artefacts, many of which can be seen (if you're lucky) in your local second-hand shop.

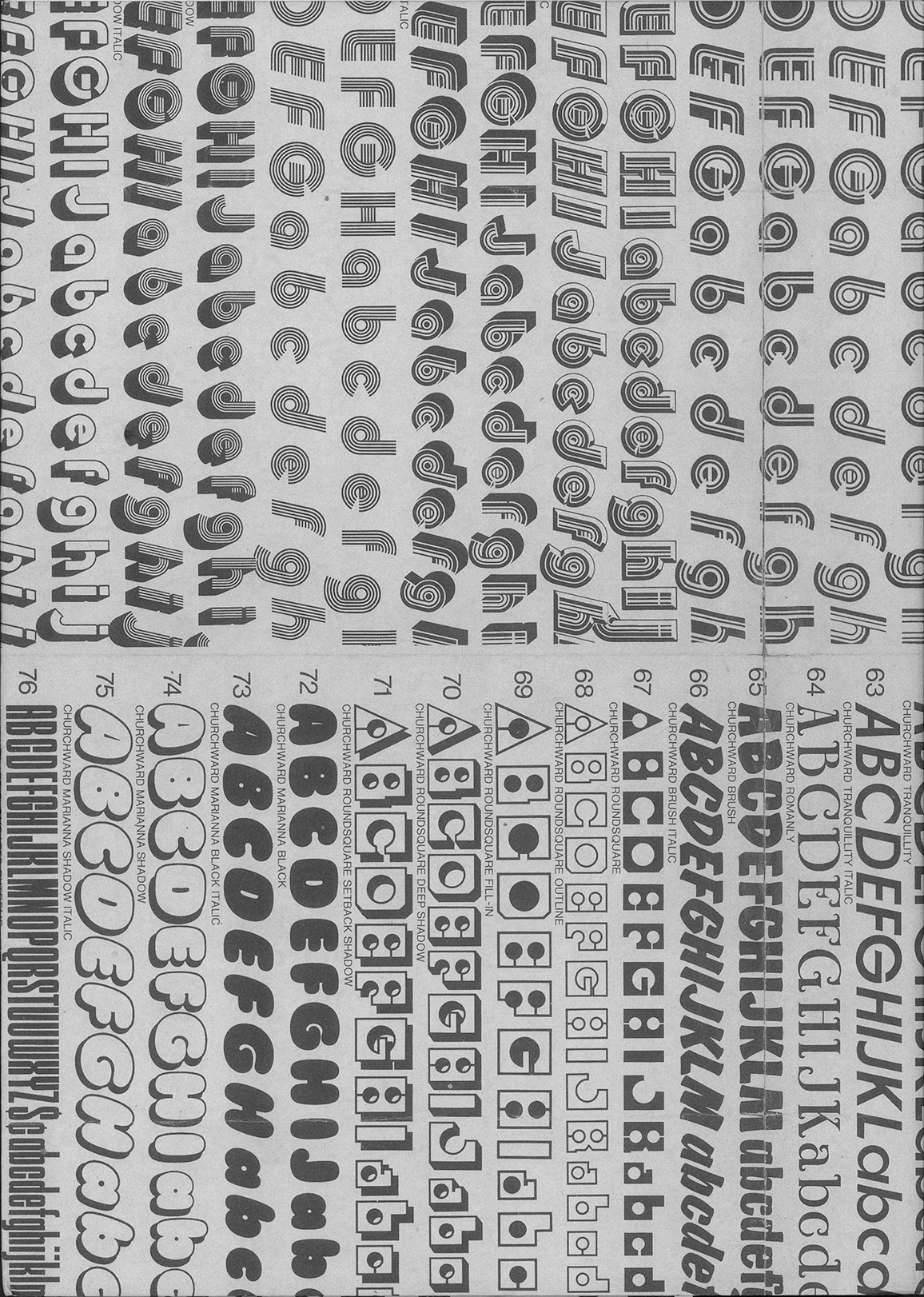

The value in understanding our visual inheritance is still, I think, accepted in both creative disciplines of design and art, although the scope of subject matter has been under continual re-negotiation, especially in the last couple of decades. If, as a designer, you are taught under the master/pupil model of art schools, it makes sense to pursue this paradigm in practice. Poor designers tend to seek out masters and mimic them in the hope that their clients won't know the difference, whereas good designers have and, I hope, will continue to seek out past designers to determine how they did what they did, apply it in changed contexts (what if Joseph Churchward grew up with an Apple Mac?) and maybe consider what they didn’t do—your “side-roads that were missed”. This seems to be one end of the speculative play that you mention.

Interestingly, within history, there has been a recent development in ‘speculative histories’ that I am hoping will be a useful method for opening up history to students of design. In the recent New Zealand example, New Zealand as it might have been edited by Stephen Levine, 15 writers move sideways towards designing. They take a ‘what if’ approach to history, changing a key driver e.g. what if the Treaty of Waitangi had not been signed in 1840?, to consider plausible past scenarios. With some adaptation, speculative histories could enable student designers to see history as a live pool of ideas, rather than a stagnant swamp.For me, the former seems like a profoundly more sustainable cultural, and even environmental, model than to believe we are continually inventing the new without regard to past successes and, perhaps more importantly, failures.

It’s interesting that you mention the materiality of things like 12" covers. I've even been known to buy an album for its cover, to later discover I also really liked the music on the vinyl inside. This demonstrates these are important components designed to seduce and attract us, but the design also speaks of the time of its production—all the limitations, constraints and creative opportunities faced by the designer at the moment of album release. And it is very difficult to fake (although read Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle, an alternate history novel where Germany and Japan won the war, and Dick writes about ‘historicity’ in a world of mass reproductions of ‘authentic’ historical artefacts). Interestingly, the idea of ‘Retro’, which is more a combination of homage and what Forty referred to as an archaic grammar, was adopted by French journalists in the 1970s (in the aftermath of massive social change in that country) to refer to nostalgic mimicry of aspects of the past. We can see the commodified form of this in the ‘new’ Beetle and Mini, and many other appliances and ad campaigns, but for me, as a historian and former museum curator, it is that materiality that gives me all sorts of clues about its making. Clues that are often excised in reproduction, e.g. a printer’s mark on a poster, or a lithographer’s initials discretely incorporated in an ornamental design. That’s magic and gold for a historian—sometimes—but usually with a lot of other supplementary evidence.

I've got to come back to book design, and your suggestion that the book could be designed prior to the research. I have no doubt this is possible, but falls into the same trap as the design following the research—too many things get determined before the materials of the situation are evident. The research and its writing are the materials of the book, and book-designers have to be responsive to content (significantly more so than with a poster say). Aaron Beehre made this point when discussing his award-winning design of Jingle Jangle Morning on National Radio. The best solution is co-design, so that the designer can shape the research alongside the researcher. I have done this successfully in exhibitions, but have yet to do with a book, where commercial imperatives are more pressing. It also requires a researcher open to a designer’s what ifs, and a designer open to a researcher’s insights into the content. There seems to have been a degree of this with Aaron’s book design, but it was produced as part of the Christchurch Art Gallery’s exhibition programme, which is a different context to a purely commercial publisher.

Finally, I have to pick up on your reference to Peter Saville, as Guy Julier, when he was here last year, discussed an interesting incident when Saville was employed to rebrand Manchester. Without knowing exactly how he went about his Factory Records designs, I’d probably prefer to describe it as design research, whether for practice or theory doesn’t much matter, in that he re-looked at historical examples in some form or other and altered them to fit the context of that particular record label at that particular time—and it worked, whatever Savage had to say about it later. More recently, having delivered the expected Manchester city logo, he then proceeded to publicly dismiss it as meaningless, and said the the real design job was to retain the intellectual capital that passed through the city so regularly but didn’t stay on. This seems to me a designer who has learned the lessons of history i.e. that a change of logo or brand doesn’t change cultures or regenerate cities, and the designer’s job is increasingly about identifying complex problems that require considered and creative human-centred solutions.

by David Bennewith

Clouds & Jan van Eyck Academie, 2009

Have just got DB’s book. In the Lynyrd Skynyrd song ‘Whiskey Rocknroller’, the singer begins: “An old stupid writer asked me one time: ‘Who are you, man? Who are you?’ Well, this is what I am...”

I’m not going to ask who you are Rev. Gunn, but there is a question of identity hanging over this book.

The question for me is: Is this a model for future design historical research in New Zealand? I’m interested to know whether you think this is a model for future design research. Let me know if you have any questions for me. You can think about the answers in drink breaks between songs.

Ok Noel, so we should try and come to some more or less sort of natural end soon. Before you leave us for Scotland anyway! Thing is I can see this taking off in whole new direction now. But it seems important so let’s see where it goes.

Firstly can I ask you to clarify a little. I'm assuming that by “question of identity” you are meaning that the David Bennewith-ness is somehow getting in the way of the Joseph Churchward-ness of the book? I’ve heard other people say this in a round about kind of way too I think. Is it that you think that David hasn’t been objective enough?

“Is this a model for future design historical research?” I can’t see why not. I do think David’s project is an exciting departure from the usual sort of artist monograph you might expect. But that’s getting back to what I was trying to get at last year... that this is a different sort of project to say Hamish’s or yours. It’s almost as much about David’s engagement with the man and the material as it is about the man himself. I think there’s a real genuine sensitivity about David’s handling of the project too though, and so in that sense I can’t see a problem. I think Joseph is quite happy with how it’s all turned out. But do you see a problem here with this as a model for historical research?

by David Bennewith

Clouds & Jan van Eyck Academie, 2009

Well, the Scottish bard said: “The best laid schemes of mice and men, gang aft agley”, and my intention to write this before I left New Zealand became a jumbo vapour trail over the Pacific. However, sitting in Edinburgh University Library with a copy of David’s book (NZ & Holland) and Herbert Simon’s The Sciences of the Artificial (US & UK) seems like as good a place to reflect on this book as any.

The identity question

My initial perception was coloured by David’s presentation at Type-SHED11. He was so close to the book, in terms of publication (it hadn’t arrived yet, you’ll remember), and in terms of the audience: New Zealand’s first gathering of international typographers, but, most definingly, Joseph and his family. I really empathised with him there; who do you speak to? How to tell someone else’s story? This is not like speaking of Robert Coupland Harding, who is long since buried, and whose legacy resides in an archive. He held to Joseph’s first drawing instrument, as a talisman of sorts, but I suspect that, because the book had been printed but not published (released to the audience), he was in a no-man’s land.

Having read the book in its entirety here in Edinburgh, I'm much more comfortable with what David, through the book, has achieved. First and foremost, it draws our attention to Joseph’s remarkable skill and achievement. In that sense it is a contribution to Design History. It is more than this though. It's a living, albeit fragmentary, resource for designers—from a poster for your wall; an enticing sampling of type specimens; a suggestive Churchward portfolio; a snapshot of Joseph Churchward and his remarkable family; the design of his type in a variety of contemporary contexts; and reflections on the business and technology of design practice in New Zealand over the past 50 years. In this way it can best be described as a collaborative working-book. By that, I mean it operates like a studio workbook, showing the process in action, reflections and diversions, but opens opportunities for further reflection and practice. I like that.

Objectivity & subjectivity

As a design social historian, my role differs from David’s, in that I regard my job is to articulate the social context as background to the design in the foreground. This is not deterministic—i.e. because of x economic force + y technological force, design z occurred—but to situate design in its particular society and culture in time. I see this as a fairly workmanlike service situation. Unless, I am directly a part of the action under examination, I’m happy to remain in the shadows, except insofar as I make explicit critical arguments about what designers did at a particular time and how those actions responded to, or shaped contemporaneous events.

Design &criticism

There is a weak reviewing ploy to criticise a book for what is not, or slightly better, what it could have been. This is not the design history of Joseph Churchward that I would like to write, but David obviously has other intentions. This, however, is not a review of the book, but a reflective conversation about the relationship of design history and practice. And there is very much a sense of an initiating and open conversation about the way this book has been designed, and about Joseph Churchward’s practice. Seventy percent of the content is Joseph’s practice, and the interleaving of Joseph’s design and business practices is a real strength of the book. Without David’s collaboration with Joseph and his design project, this material would have remained isolated from a community of interest. This is not wilful neglect by historians, just the state of the field in New Zealand —open to discovery, scholarship and furthering practice. And in this regard New Zealand differs markedly from Design History in other industrialised nations. It is not that there has been no design here of note, it’s just a function of the basics of scholarship only beginning to be applied here.

Is Joseph Churchward a significant design practitioner? Undoubtedly, by virtue of the sheer body of work (600 typefaces!), but also in the way he extended his practice in terms of stretching the parameters of font variation (“no-end”), his entrepreneurial design pitches, his international networking and competition success (from a remote island nation), his responsive application to current technologies (the Apple Mac excluded), and his anticipating demand from within the advertising industry in particular. Is he a ‘pioneer’? Here, I’d offer a more qualified ‘no’. Harding was an international type designer in 19th-century New Zealand, albeit in an age of metal type production and the emergence of mechanical composition. A gap of some 50 years separates them, but these two were no isolated geniuses, and were aware of, and responded to contemporary developments, so it seems plausible that others were similarly motivated and we have yet to discover them. As soon as you have ‘pioneers’, the spectre of a canon arises as Paul Elliman alludes to. Joseph’s practice might be inspirational for young designers, both here and abroad, but it also contains important lessons about what it takes to survive financially and creatively as a designer: family, business acumen and entrepreneurship, adaption to technology, craft and skill, and pleasure in and satisfaction with what you do. The risk of elevating them to individual creative genius is that we discount all the support mechanisms that make their practice possible. I guess that’s where I see social history kicking in.

So what’s missing? The thrill of the chase and discovery is there, and I guess it’s a guilty pleasure for me to see David record the opening up of his subject, but there are leads that require further research and clarification. This is the historical discipline of mapping all available resources and correlating them in order to develop critical arguments that place Joseph’s practices in his time. David observes that Joseph’s packages “disobeyed chronology and theme” (p.12), and David, to a degree, has respected that to try to place him in the present. He does this successfully through practice in the section ‘Churchward in Use’. But two contexts that require further contextualisation are the advertising industry itself and the transitional technologies he operated with, namely phototype and transfer lettering. As means of type production these literally represented a graphic transition between hot metal and digital foundries—both an opportunity for his practice and the reason for its near disappearance into technological redundancy. This seems crucial to locate his practice within an emerging profession of design that was an integral part of advertising.

There is one last reversal in this book I'd like to draw attention to. Many of the popular New Zealand Design books of the last decade have achieved relative commercial success because they appealed to a broad audience. These have value to designers as source books, but offer little in the way of insights into the design process, past or present. By contrast, this book is designed for professional designers, and so more narrowly limits its audience. But, as suggested above by way of comparison, this is by no means a negative characteristic. However, a more broadly conceived design history might open up this remarkable story to audiences for New Zealand history and assist non-New Zealanders to recognise and understand the context of South Pacific design. The problem is evident in Paul Elliman’s essay, where his only way into this culture is by way of Keri Hulme’s literature. There is just no historical or cultural anchor by which he can assess these designs, and yet when I see Joseph’s designs for the All Black jersey and the South Pacific television of TV2, they just resonate with with the culture I grew up in, and there’s a certain sadness at the missed opportunities.

Design futures & history

So, Jim, not Design History as I have known it, but close to some of the ways I have practised it in terms of exhibitions. The last part of the equation, now that we’ve covered histories and criticism, is futures. I still see value in a disciplined historical approach to the subject, which is to both reconstruct history and attempt to place our readers and students in it, but regard David’s project as a complementary and operational approach to a serviceable historical record. For me, it’s both/and, not either/or. The section ‘Churchward in Use’ (pp.225–40) abandons history and puts Joseph’s faces to the test in a variety of contemporary contexts. I see this as a kind of experimental time-test. Do they still work? Some better than others, as you’d expect, but where biography and typography collide in the Well-ington lightbox project 3 Daughters (p.234), David succeeds in paying tribute to his subject and revitalising both their practices. Perhaps then, more importantly, David’s critical and creative practice has played no small part in reconnecting Joseph’s twentieth-century typographic legacy to twenty-first century digital design. A sustainable design culture in New Zealand requires a reliable account of its history, robust criticism, new theories that inform practice, and new practices that inform theory. David has ambitiously tried to address all aspects in this diverse account of a single designer, but I would like to see the weight more evenly distributed, and to zoom out a little to see the field of New Zealand design made accessible to as many people as possible. We need critically astute, innovative, entrepreneurial and creative practitioners that respond and contribute to our culture in ways that Joseph did and in ways that he had not imagined if, in Herbert Simon’s words, we are, all, to “change existing situations into preferred ones.”

Hope that’ll do Luke, and sorry for the delay. Listened to Solomon Burke’s Nashville as a coda as I crossed the meadows tonight.

I know you want this in the bag, but thought I’d fire you this link to a current issue with the logo for the Glasgow Commonwealth Games that appeared in the Scotsman.2 This brings up the relationship between design history and criticism—to understand the value of the past to the present and possible design futures.

Here is an ethical issue about whether designers can recycle their own designs, a common enough practice, as we all know. However, in this case, the design is a regional, national and international brand for a major sporting event that is funded by a significant amount of public money—£90,000. So, what’s the problem here, as the additional use of colour and line in the ‘new’ logo and the fact it was designed by the same company probably satisfies legal intellectual property requirements? Essentially, it’s a failure of design history, in both senses of the wider development of ethical practices within the industry and a documented record of the economic and cultural value of original design, as well as the institutional history of the firm. In the unlikely possibility that the designer was unaware of this design by his or her own company, it is then a failure of design research.

This design is now in the public domain, and the designer and/or company failed to understand that the process also belongs to the public domain. We know it takes less time to adapt rather than create a new design, and the public are rightly indignant that the designers have not fulfilled their professional responsibilities. This would be like a lawyer using a standard Real Estate contract for the conveyancing of a complex house sale and purchase, rather than drawing up a specific contract utilising their knowledge and expertise within the law.

Design History matters—to design companies that want to be professionally successful and to the users who are represented by their designs. One well known graphic designer, whose name I forget, said that he did 100 designs just to get rid of the cliches. Maybe if some of that time was spent on design research, the designer would only need to do 10–20. For example, a quick search of Commonwealth games logos would demonstrate the success of Colin Simon’s iconic design for the 1974 Commonwealth Games in Christchurch because of the way it incorpo-rated a New Zealand (NZ), Commonwealth (Union Jack), Games (Xth) and time specific (1974) event, but also the radical break from the imperial symbolism of previous logos. And, as my colleague Gavin O’Brien has demonstrated, it was undoubtedly influential on the subsequent three Games’ logos.3 The historical development actually strengthens the logos by their ability to integrate host national and event international identities.

Don’t feel obliged to include this, but thought it might be of interest—and as for the woeful 2006 Wellington logo bid, no wonder they didn’t get it!

I’d been getting myself all tied up in knots lately trying to figure out what to write back to you when you beat me to the punch and that last email came in. So I want to back up slightly here...

I was feeling a bit unsure about ending this on a critique of the Churchward book. It seemed too specific, and It wasn’t what I’d had in mind when we’d started this. But then looking at the dates here I realise this communication has gone on for over two years now! Of course things are going to move about a bit over that amount of time. Anyway I am genuinely interested in your take on David’s project, and I do still think it serves as a good example here.

I think all your criticisms are perfectly fair and valid, but, like you say, this isn’t the book you would have made, and David has had other intentions. So what I’m really interested in here is that I see you and David coming to this similar sort of place but from very different backgrounds and perspectives. It’s the nature of this overlapping of cultural spheres that interests me—a kind of design/history venn diagram, with the bit in the middle there.

In that sense I liked your description of the Churchward book as a “collaborative working-book”. That has the ring of getting your hands dirty about it, and that sort of practical engagement with material I was getting at before. Likewise your comment about it being an “operational approach to a serviceable historical record”. That word ‘operational’ sounds right too (although I might be putting my own spin on your words here?).

Anyway I was trying to think what to make of all this when I received Bruce Russell’s text for this issue. It’s strange, we never plan to have thematic connections within each issue, but they seem to happen regardless, and as an editor it’s nice to know I can just run Bruce’s text after this one. Quickly reading Bruce’s piece, but with our conversation still very much at the front of my mind, I came across this: “He was pre-occupied with the fact that we only know ‘cultural artifacts’ at a remove. While traditional critics and art historians obsessed over the original significance of things for their creators and first privileged recipients, Benjamin was the first to make our ‘removal’ from the creation of an artefact into a virtue—a path to new knowledge.”

That’s Walter Benjamin he’s talking about there obviously. And, at the risk of offending both you and Bruce, I want to say this feels like it has something of what I’m after in it too. He carries on: “His category of experience was intended to de-laminate the work, to dissolve it in an acid of time and uncover its meaning for us... He was striving not to explicate what these things meant in themselves, but what they mean to us, at the point of their reception.”

I can’t help but feel like he could be talking about David’s project here—specifically the nature of his engagement with Joseph’s work. This also describes what I felt like I wanted to try and do with the Robert Coupland Harding material. Maybe it’s just a matter of emphasis? You want a deeper picture of the social context of the specific time the work was being made. I want to see if I can apply that work to my everyday experience as a designer here. And of course there’s certainly some overlap there. So I can see my venn diagram working I think. We need each other obviously.

Which brings me to another point—the community of design here in New Zealand. Another can of worms, but I’ll be brief. I mentioned it in my introduction to the Harding reproductions, this strange gap between bibliographical historians and contemporary graphic designers. I was really excited when I met you actually—you opened up a world of knowledge I hadn’t known existed. Equally I think when you spoke at TypeSHED11 last year, a lot of the designers in the audience were surprised and excited by what you were showing them. The problem is that conference was the one and only time I know of anything like that happening in such a successful way here. So what I’m getting at is that this ‘needing each other’ is something we could work on. Ways to work together more perhaps? It’d be interesting to see what sort of book you and David might make together.

Before we all run off hand-in-hand though, there’s your last email and those Commonwealth games logos. More than the row over the logo for the Glasgow games, I was really interested in the link to all the previous identities. The New Zealand one from 1950 also stands out as a departure from that imperial symbolism (crowns and sheilds), and seems to be the most modern (in a nostalgic sense) until Colin Simon’s thoroughly modernist mark for 1974. I’m not so convinced by the Auckland 1990 one, but certainly looking through these you could be forgiven for thinking that NZ might have a unique and interesting history of graphic design.

At the time of writing Noel Waite was a Senior Lecturer in Design History at the University of Otago. This conversation is the result of email correspondence that took place between May 2008 and April 2010, and which will no doubt continue on from here. This is an edited version of the original communications which ran to over 10,000 words.