Two Works by Simon Glaister – Leonhard Emmerling

Simon Glaister

2008

St Paul Street gallery foyer

Photographer: Simon Glaister

I.

A sculpture made of gold leaf covered studio partitions forming the letter ‘I’ hung in the high shaft-like foyer, spreading over several floors.

It hung vertically downwards as a shining monument to a vertical mania daring to exhibit its own complete emptiness.

There were two formal points of reference for this work. Firstly, paintings by Colin McCahon which are to be understood in the context of his religious work paraphrasing elements of advertising graphics, such as: I AM of 1954 (Hocken Library, Dunedin). The second point of reference was Michael Parekowhai’s The Indefinite Article of 1990 (Dunedin Public Art Gallery), a sculptural adaptive transformation and reinterpretation of these paintings which play with the ambiguity of the word HE in the phrase: I AM HE. As well as the English meaning: ‘I am He’, in Te Reo ‘he’ can also be the indefinite article ‘a’ and when spelled ‘hē’ can mean ‘wrong’. Then the title could be interpreted as ‘I am a/anybody’ or ‘I am wrong’.

McCahon’s paintings are reassurances of the promise that HE is present and his late works, which represent delirious glossolalia of doubt and manic repetitions of biblical promises of salvation, are testimony to his dire need to invoke HIS presence. Depending on which translation of the old testament name for god, YHWH, one prefers: “I am who I am” or “I am the ‘I am’” or “I will be who I will be”,1 one might ask what consolation Colin McCahon drew from the evocation of HIS presence, as this tautological encapsulation does not involve HIS presence but rather HIS radical otherness and absence. “For Israel the name Yahve signifies the mystery of Yahve’s identity and does not reveal or designate Yahve’s essence.”2

This emptiness is reflected through the emptiness from which the enunciation of the “I” arises and through the emptiness which this enunciation generates.3 The subject draws itself up into the hollow and pompous illusion of the knowledge of oneself as a reflection of a divine self-image, and into the dream of “possessing oneself”.

The “I am who I am” rises vertically in the glorious terror it exerts over everyone who must bow their heads below: the inhabitants of the horizontal level.

II.

According to Dugald Stewart, the sublime is associated in the first instance with the category of height.4 Climbing to the top of a mountain is a sublime activity because it requires the application of physical skills which far outreach those which are required from somebody who goes for a stroll across the flat countryside. It is the struggle against gravity which lends sublimity to climbing mountain tops. The victory over the laws of physics, the overcoming of the limitations they impose on us, lends our heroic efforts the character of the sublime.

The divine is the suspension of the material laws of physics. In this respect there is a natural relationship between mountains and gods. They prefer to inhabit the mountains rather than the human lowlands. Nymphs may live in springs but true gods reside on peaks.

Just as the mountains with their raging storms, icy coldness and ruggedness instill fear in the hiker, the angry gods terrify the believer. For this reason fear is one of the reasons for the feeling of sublimity. Stewart goes as far as to assume that fear is the essential feeling of believing and understands the feeling of sublimity as the derivation of religious terror.5

Soaring to intellectual heights can be seen as a metaphor for the mental activity required by somebody who wants to leave behind the lowlands of mundane thinking, the quagmires of the dishonest subtilising of his contemporaries, the swamp of contentedly mulled over lumps of masticated thought. And this metaphor seems to be built on the analogy between gravity and its physical conquest. Enlightened men of all kinds climb mountains. Being able to achieve great heights is evidence of the chosenness of a person, who is free from the manacles of base humanity. Those who want to think must first of all begin with a criticism of gravity—so it seems. Only then can they soar to those ethereal heights from where they can look down and chart the human zoo in all its pitiful mediocrity.

Man in the vastness is like a post trembling with the tension between the ground on which he stands and the height to which he is drawn up.

III

The figure can be viewed as providing a structure of how man thinks about himself through its paradoxical elements: the expansive ground and the post rammed into it, the horizontal and the vertical, the expansion and the tapering, the mass and the individual, the duration and the event, and the communitarian opinion and the truth. Because not a single element can be taken from the figure without collapsing it, no element can be assigned superiority above another. The paradoxical elements simply stretch humanity in a tension which cannot be released without destroying humanity itself. It is evident that such destruction of mankind is a possible option.

In this respect the masses do not exist, just as the sage does not exist. The masses only exist in terms of the sage, and the sage in terms of the masses, and both their relationships to each other are again bipolar in themselves. The masses hate the sage, the prophet. They hate to be challenged and they ask with good reason what the secret is of all those who appear to hover high above their mundane knowledge. How do they succeed in guaranteeing the complete and permanent inefficacy of their billowing words? How do they manage not to draw them, the great unwashed, up onto those higher plains from which they are accustomed to looking down in such a sympathetic, knowing, and enlightened way? How are they able to so comfortably maintain the discrepancy between their superior knowledge of how the earth and mankind can be saved, and the actual misery of this world? The accusation against God: Comforter, where, where is your comforting?6, applies equally to the sage who is either in cahoots with him or claims to have snuffed him out. Everything turns him into a repulsive, revolting figure: his stubborn insistence that his view is privileged; his enlightened smile which acknowledges the questions painfully stuttered out by the horizontal masses, cursed by gravity and restricted by the horizon; his indulgence with which he absolves himself when challenged with the banal problem as to the value of his commanding view.

At the same time, the masses in their self-contempt love to prejudge everyone who roars more loudly, argues more crudely, or attacks more punishingly, as the exception to the rule which the masses themselves constitute. The exception which interrupts the permanent continuity, the conformity of the unchanging existence, and the indistinguishability of the mumblings, saves the masses for a moment from themselves by opening a gap towards the pole which forms the paradoxical abutment of the figure and which may be construed as being human.

In a similar way the sage, the prophet, the herald, the enlightened, is bound to the masses. He despises them, regards them as immature, clumsy, dull, uncultivated, slow-witted, crude, brutish and therefore condemned to perish. In cathartic firestorms they will be forced to a cleansing which their weakness of will, blindness, inferiority, and stupidity otherwise precludes them from undergoing. The ultimate cleansing will be their obliteration and complete extermination, so that something new will be able to grow out of the land within the sage’s purview. On the other hand, the sage needs the masses in order to promulgate, to prophesy, and to instruct. All his knowledge is useless without the masses, because the sole purpose of this knowledge is to lead them out of the horizontal quagmire and to save them. His task is to prepare the masses for salvation, however, they can only be saved en masse, in their entirety, in their totality. The truth of the sage is total and applies to everybody. Therefore, as everyone is subject to the truth they must be subsumed by the masses and remain there. The individual who refuses to accept the validity of the truth, which is represented by the sage in its totality, must be obliterated and exterminated, either physically or spiritually.

Both, the masses and the prophets, make sure that the prophets remain prophets and the masses remain the masses. While the masses yearn for the prophet, honour and admire him, they also hate anyone who refuses to follow, denies communal admiration, stands apart, contradicts or remains silent. And just as the prophet despises the masses, a sentiment he shares with them, he also fears the individual who does not accept his word because he excludes himself from the message which is meant for everyone.

One could investigate the endless variations of the duplications of self-contempt and self-love, and of the internal interlacings (the prophet as an incarnation of the masses projected in front of himself, creating the presence of a totality which he could not otherwise access; the masses which copy themselves into themselves as the representation of an exceptional figure, etc.), which mould mutually into each other and brace the poles of the paradoxical figure against each other. However, there is no shortage of literature which depicts this reality. There is absolutely nothing mysterious, enigmatic or new to be discovered.

IV.

In the poly-contextural, functionally diversified, poly-culturally configured society there remains nothing more than catastrophic terror which in its massive one-sidedness and ruthlessness is in a position to generate the sublime. The sublime produced by terror is the residue of the religious with no god. Terror shows the un-negotiable as truth and the particular, paying no attention to other particularities, as universal.

Terror has all the characteristics of the religious: its instantaneousness, surprise, and suddenness; its effectiveness and ruthlessness in turning into reality what was until then only words; its indisputable factuality in which it manifests itself; its inaccessibility to all argument and objection; its total disinterest in the impact of its ruthless interests; its overpowering and conquering nature; its permissiveness to allow those who call on it to hide behind the supernatural and the numinous-anonymous.

In a single act terror cuts through the manifold patchwork which connects the countless functions, cultural islands, social niches, hierarchies, structures, and organisational networks of a society with each other. It establishes the actuality of its own homogenous and simple truth instead of the fragmented, contingent, horizontally and vertically tightly wound complexity of a society far removed from any quest for truth.

By submitting its victims indiscriminately to the effect of a single, determining act, terror transforms the paradoxical horizontal and vertical figure through the act of extermination. It cuts through the continuity, transforms the multitude of individuals into masses, the vertical into the horizontal, and establishes itself as the only one which may claim the right to exist in place of the masses. In the place of the totality of the contingency it creates the totality of a unique necessity which is so self-evident that it would be pointless to convince oneself of it or to believe in it.

V.

The comment made by the composer Karlheinz Stockhausen that the terror attack of 9/11 was the greatest art event of all times7 not only unleashed a wave of outrage but also proved how closely terror, as the residue of the religious, is connected to the feeling of the sublime. His daughter’s refusal to continue to bear her father’s name shows in a twisted way all the elements of the transformation according to which the necessity to document the dismissal of a former persona through a name change becomes unavoidable.8 Stockhausen involuntarily embarked on the path to seclusion, banishing himself from mainstream consensus. Self-styled religious idiosyncrasies in all their naïve innocence collide with the inability to separate the sublime from the religious, and to keep both away from art. As a result, one single rhetorical faux pas was able to generate this entire wretched imbroglio of aesthetics and ethics.

It would be flippant to see Stockhausen as misguided, having in his pitiable obstinacy failed to recognise that the aesthetic evaluation of an event unacceptable in ethical terms cannot be condoned ethically. Yet, it makes no difference that the terror attack of 11 September 2001 was not intended to be a work of art, and therefore Stockhausen would have clumsily botched up his categories. The source of the scandal was in even attempting to apply the criterion of the aesthetic to an event which in its ruthlessness completely filled the space of reality, and in suggesting, even if only theoretically, an alternative name for the space occupied totally by the terroristic fact.

The sublimity of terror left no space for the ‘As-If’ on either side of the fault line.9 Apparently Stockhausen had ignored the fact that even though the entire avant-garde, mesmerised by Europe, toys with crossing the line between real and fictitious reality, between the world of ‘facts’ and the world of the ‘As-If’, it would never act this out in earnest at any point in time, and indeed it can never be permitted to do so. Apparently he had also ignored that this game meets all aspects of the definition of what Habermas derides as a nonsense experiment.10 The taboo Stockhausen violated was to actually cross the line, an act from which the avant-garde derives all its heroism and infantile rhetoric, and to pronounce that this action, carried out in earnest, had always been precisely the dream of the modernists. Rather than doing this with intent, it may have been the result of an incomprehensible and whacky naivety which can only be explained by his Venus origins. The incomprehensible reverence which is shown to André Breton, the blustering icon of surrealism, seems ridiculous in the face of the scandalously naïve earnestness with which Stockhausen conceptually radicalised what Breton with his toy pistol in his hand had conjured up as a mere fantasy.11

Not art but terror is the medium of the sublime. In the same way as religions do not tolerate pictures as images of the space beyond totality, the full occupation of which they lay claim to, terror does not tolerate art. The proof of art’s weakness is laid bare in its retrospective attempt to profit from its sublimity through quibbling and snivelling explorations of the border territory occupied and made taboo by terror. Not even a superfluous water-colour of a pond in a meadow in early spring could show this weakness any more clearly.

VI.

Room I:

The exhibition room had been completely cleared out (including office and store rooms, etc.) making it unusable for the staff. There was nothing but a cross-shaped concrete sculpture. In a laboratory the sculpture had been subjected to seismic forces to the point of structural failure, the effects of which could be clearly seen. This horizontal sculpture was in contrast with the towering pillar in the centre of the space of which it was a replica.

The cross shape of the concrete sculpture was modelled on the pillar, but it was restricted by the physical limitations and capacities of the laboratory which could only cater for objects of a certain size making it impossible to provide a full replication of the pillar’s length.

The shape of the cross functioned as a symbol of suffering, as an abbreviation for the human body lay prone by catastrophe. However, as a religious symbol it also represented the memory of the power of the sublime, which is in fact responsible for invoking the suffering it recalls.

Simon Glaister

2009

Pushover exhibition at St Paul Street (gallery 1)

Photographer: Simon Glaister

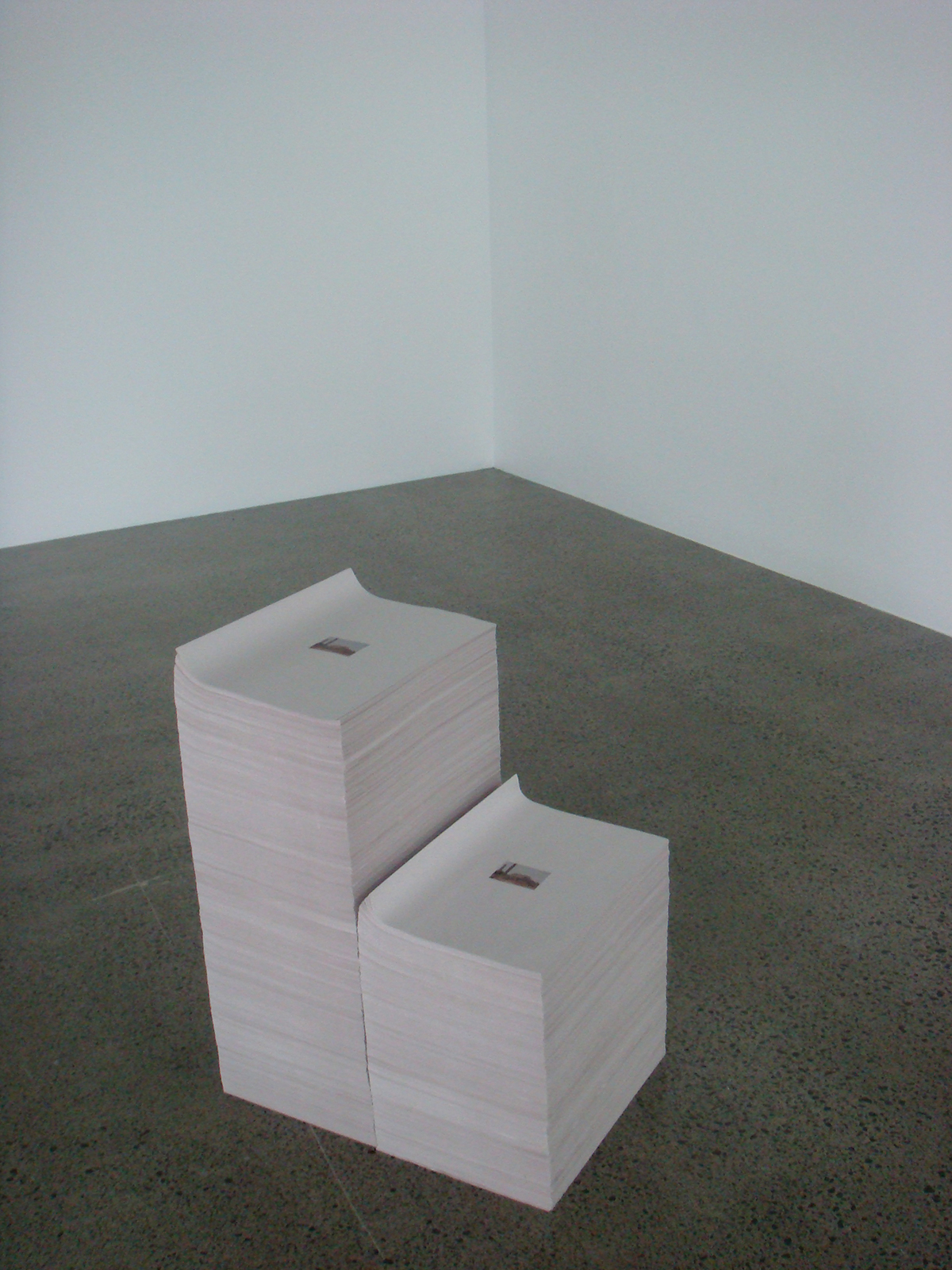

Room II:

There were posters of the Parthenon, of a library in San Francisco which had been ruined by seismic tremors, of a building which had slipped as a result of the Kobe earthquake, and of the World Trade Center at the time of its construction. They were initially piled neatly on top of each other but after a few days the visitors had spread them across the floor of the exhibition room.

The exhibition evoked the image of terror and the irruption of the vertical. In the absoluteness of its tautological selfness, of its completely empty and absolutely particular self-identity, of its disinterested interest in the individual and the masses, riveted only by the totality of its self, this verticality gives rise to the horizontality of all that which is not identical with it. The muttering of opinions, the cacophony of the unimportant, transient collective statements and individual opinions are turned into rubbish, into paper rain which together with the dust, the rubble and the human bodies falls down on the plain created by the vertical as the image of all it must violate.

Simon Glaister

2009

Pushover exhibition at St Paul Street (gallery 2)

Photographer: Simon Glaister

Footnotes

Ernst Bloch, Das Prinzip Hoffnung. Frankfurt am Main: 1985, Vol. III. p.1457 et seq. ↵

Walther Zimmerli, ‘Das Problem der Sprache in Theologie und Kirche’. In: Deutscher Evangelischer Theologentag. 1958 (ed. W. Schneemelcher). p.12. ↵

Giorgio Agamben, The Remnants of Auschwitz. New York: 1999, p.116 et seq. “And yet, in saying ‘I’, ‘you’, ‘this’, ‘now …’, he is expropriated to all referential reality, letting himself be defined solely through the pure and empty relation to the event of discourse. The subject of enunciation is composed of discourse and exists in discourse alone. But, for this very reason, once the subject is in discourse, he can say nothing; he cannot speak.” ↵

Dugald Stewart, Philosophical Essays. London: 1810. p.381. ↵

Ibid. p.402. ↵

Gerald Manley Hopkins, ‘No worst there is none’. In: Poems. London: 1999 (1918). p.41. ↵

The exact wording of the interview under http://www.swin.de/kuku/kammchor/stockhausenPK.htm (accessed 13.9.2009);

http://www.stockhausen.org/musiktexte_hamburg.html (accessed 3.10.2009)

musiktexte 91, Köln 2001, p.69–77. ↵

Peter Sloterdijk, Du musst dein Leben ändern. Frankfurt am Main. p.353 et seq. ↵

Jacques Rancière, Ist Kunst widerständig? Berlin: 2008. p.27: “The aesthetic difference must always be established in the form of the ‘As-If’.” ↵

Jürgen Habermas, ‘Die Moderne – ein unvollendetes Projekt’ (1980). In: Jürgen Habermas. Die Moderne – ein unvollendetes Projekt. Philosophisch-politische Aufsätze 1977–1990. Leipzig: 1990. p.46. ↵

André Breton, Second Manifest of Surrealism. Paris: 1930: “The simplest Surrealist act consists of dashing down into the street, pistol in hand, and firing blindly, as fast as you can pull the trigger, into the crowd.” ↵