Max Hailstone Treaty Project Revisited – Jonty Valentine

Max Hailstone

1990

The tension in the room was palpable. University of Canterbury, Ilam School of Fine Arts, September 1990, sunrise. A group of us were quietly gathered inside the Ilam gallery: about twenty students, faculty, members of the public and kaumatua. It was one of those times when I instinctively felt nervous because it was clearly an important occasion: the feeling in the room was heavy, solemn, like a funeral really. We were there for a tapu-raising, for which the focus was the ten large screen-printed sheets framed on the walls of the gallery surrounding us. The sheets were of enlarged marks indexing the signatories of New Zealand’s founding documents: the Declaration of Independence and the Treaty of Waitangi. I also felt nervous because I had no idea what the unfamiliar cultural protocol was. And even more, although I wanted to, I didn’t really understand why we were there.

In 1990, New Zealand celebrated the 150th anniversary of the signing of the Treaty [of Waitangi]. My then tutor Max Hailstone, the head of the Graphic Design department at University of Canterbury, undertook a project to commemorate the sesquicentennial… In a perhaps untimely (in 1990) late-modernist gesture, these posters abstracted the signatures from the Treaty text (the contract) and historical context. The context/s in which the project was subsequently interpreted resulted in various readings of the project’s meaning.1

That’s the start of what I wrote about the project in The National Grid #1. Then, it was part of an article about the auratic qualities of a number of significant documents. I think it deserves another go.

As a young undergraduate student at Canterbury when Max was doing the project, I knew that it had become increasingly controversial, but I didn’t really understand how a work of graphic design could become so contentious that it would need a tapu-raising before it could be released to the public. I’d like to set the scene more now with the help of twenty years of hindsight—to more fully address the different “context/s in which the project was subsequently interpreted”. To start to do this I’m going to gather together and quote (in an extended manner) from a number of texts that directly address or contextualise the project. Also, I want to try to make the case for why it should be seen (recovered) as an important New Zealand graphic design project. Because even though Max was first and foremost a graphic designer, it never really was discussed or written about from that cultural sphere in this country.

Visible Language and Typografische Monatsblätter

Max died unexpectedly in a car accident in the United States in 1997. So unfortunately he is no longer here to speak for the project. But I do want to begin with Max’s side of the story. I believe the only written accounts by its creator are two nearly identical articles published a couple of years after the release of the project. One in the US graphic design journal Visible Language and the other in the Swiss typographic design journal Typografische Monatsblätter (TM), both published in 1993.2 So as an introduction to the project from Max—this is from the introductory abstract to the article in Visible Language:

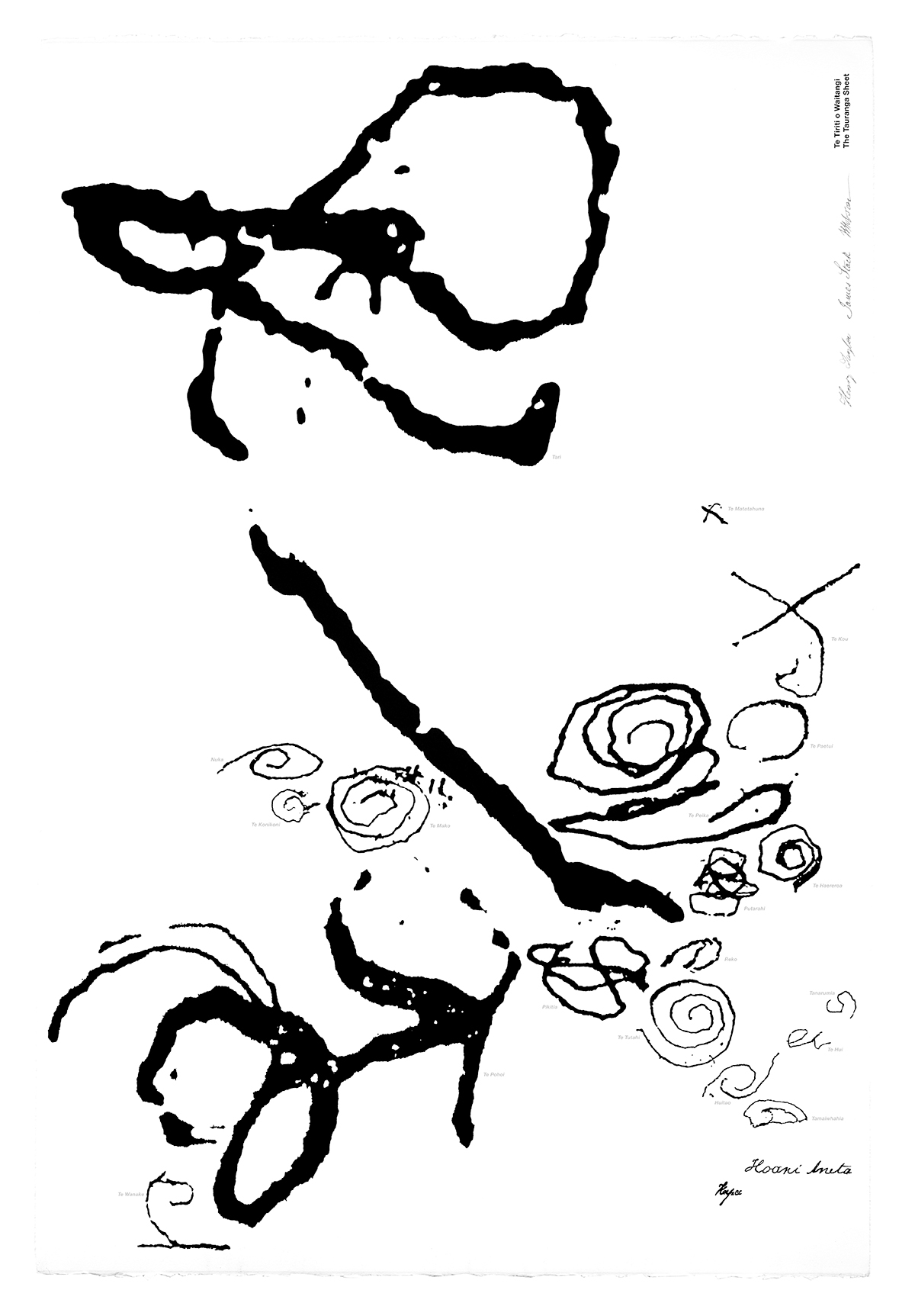

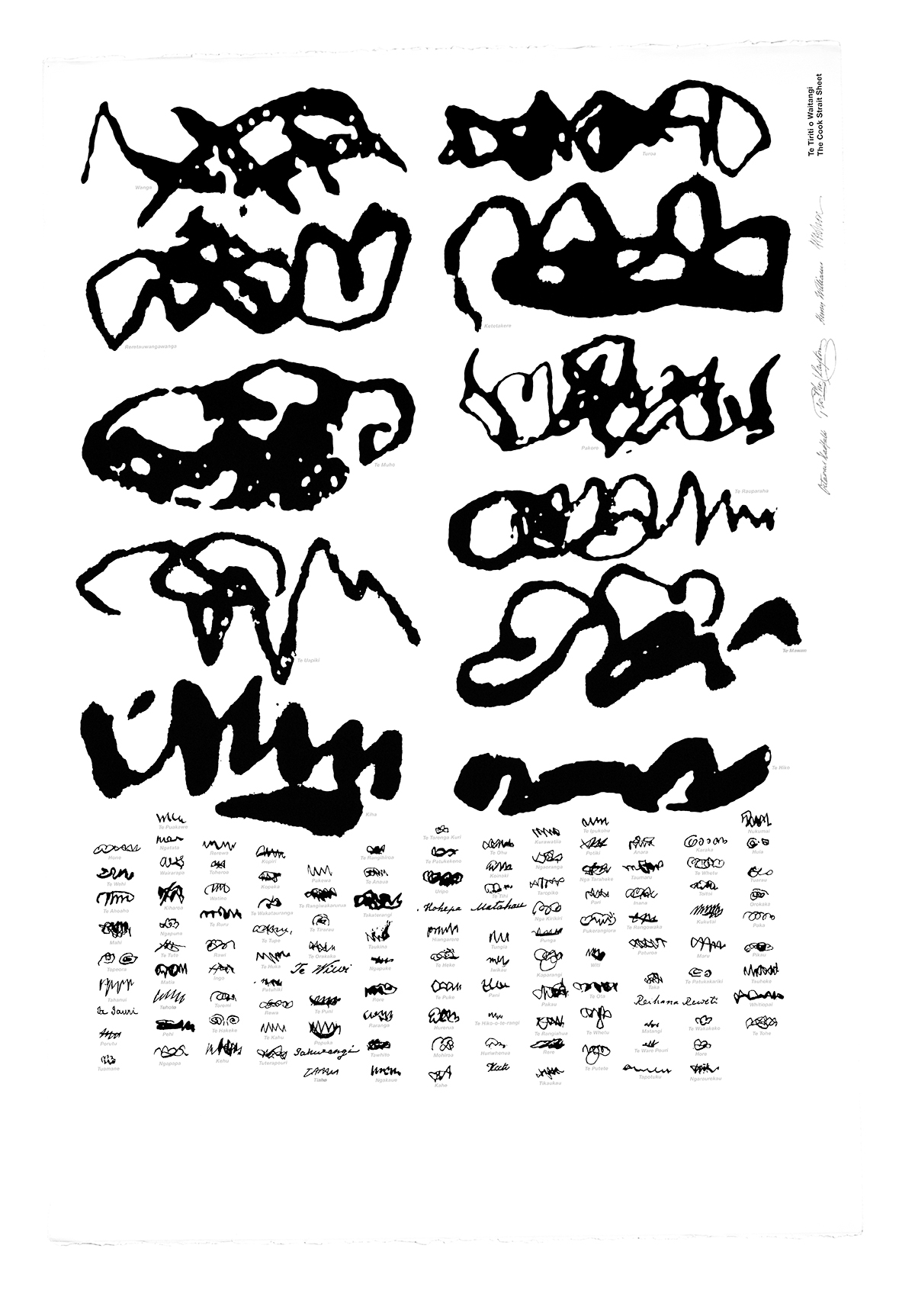

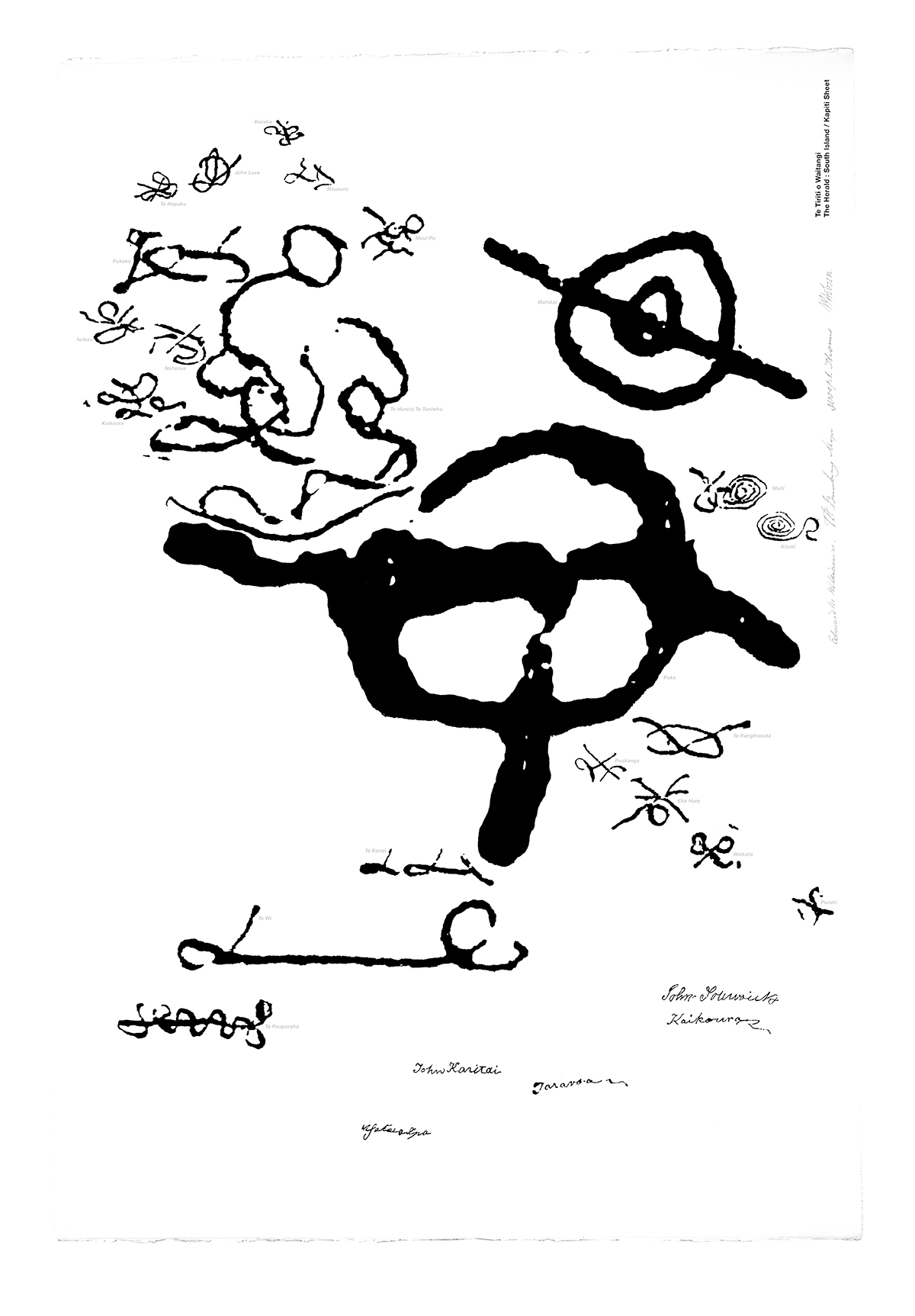

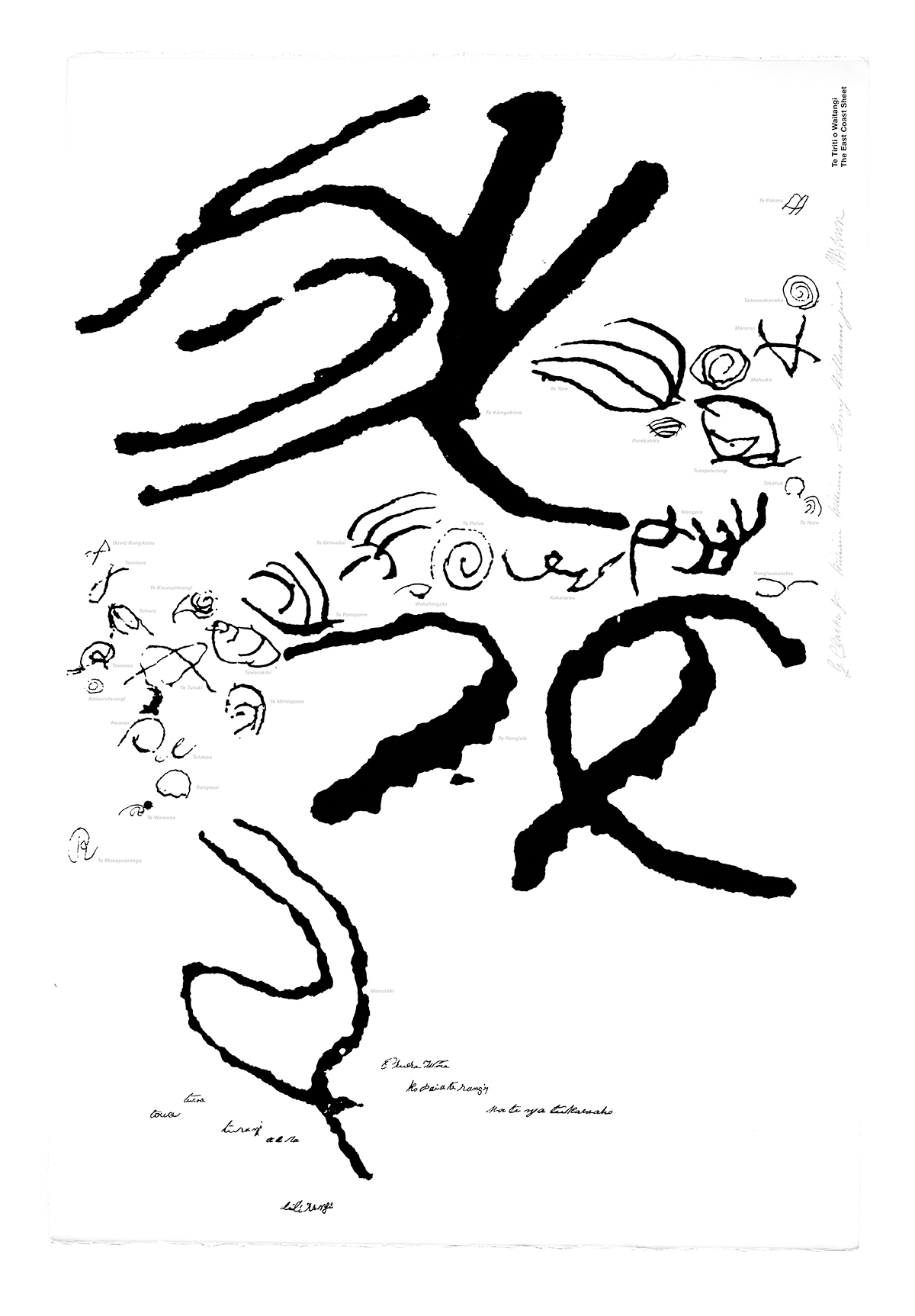

The founding document of present day New Zealand, the nine sheets of the ‘Treaty of Waitangi’, is explored in terms of the Maori chiefs’ signatures and their significance in European and tribal custom. The original signatures were extremely small as the space designated for them was only 5mm—they were dominated by the attempted English spelling of the chiefs’ names. The author [Hailstone] enlarged the signatures in order to better examine their form and study their inter-relationships. These signatures were further enlarged and manipulated to become a series of nine silk screen prints celebrating the event.3

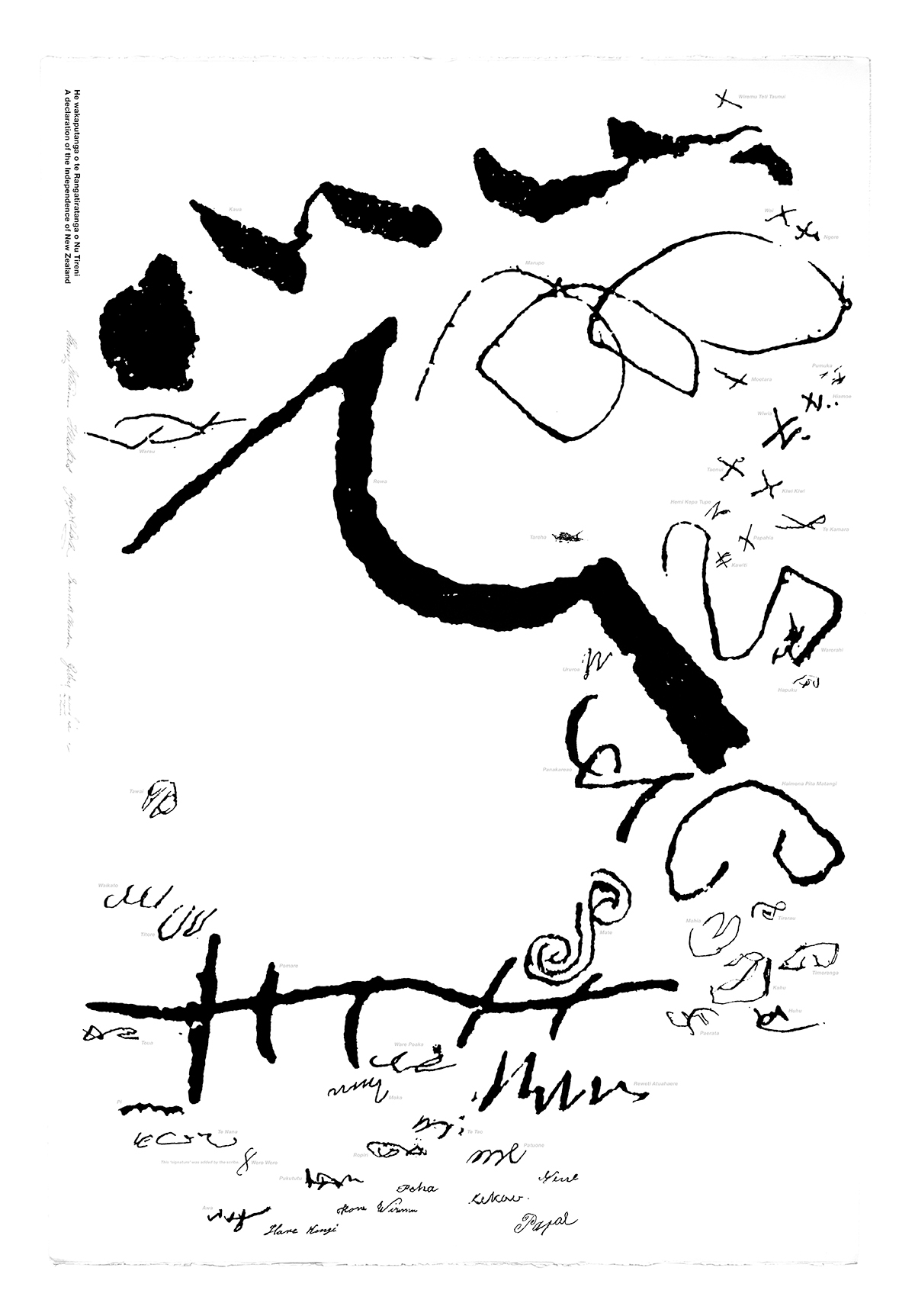

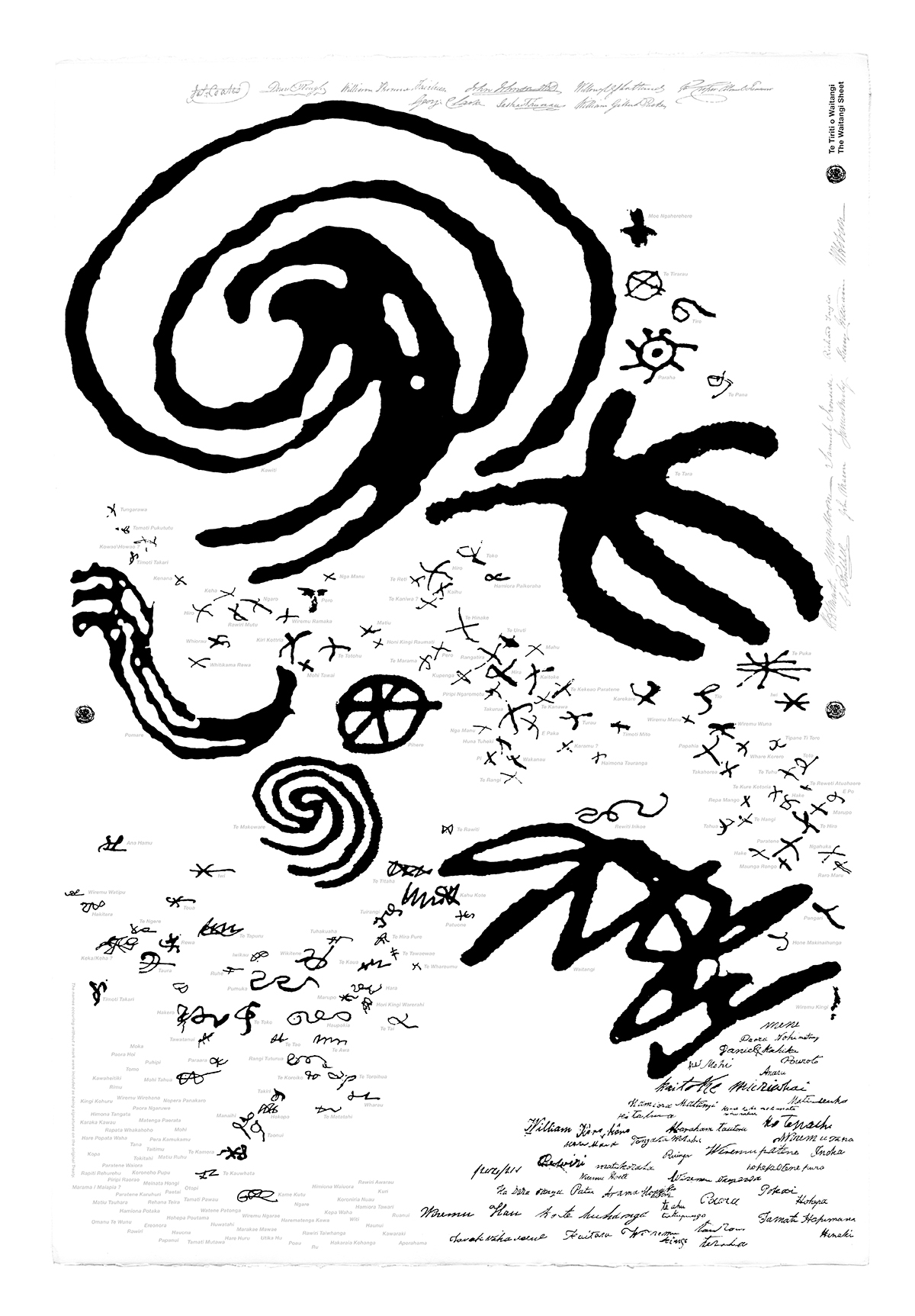

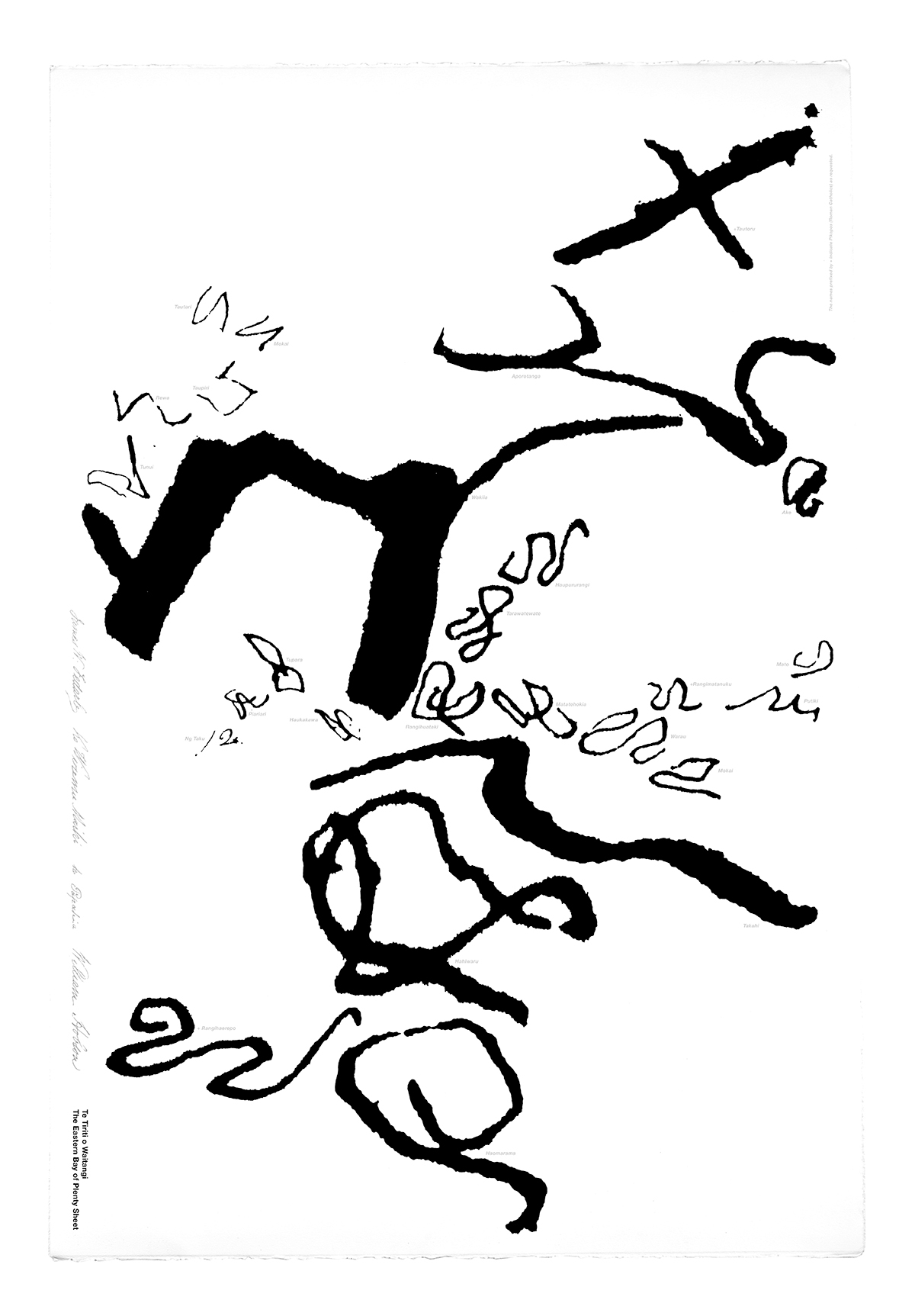

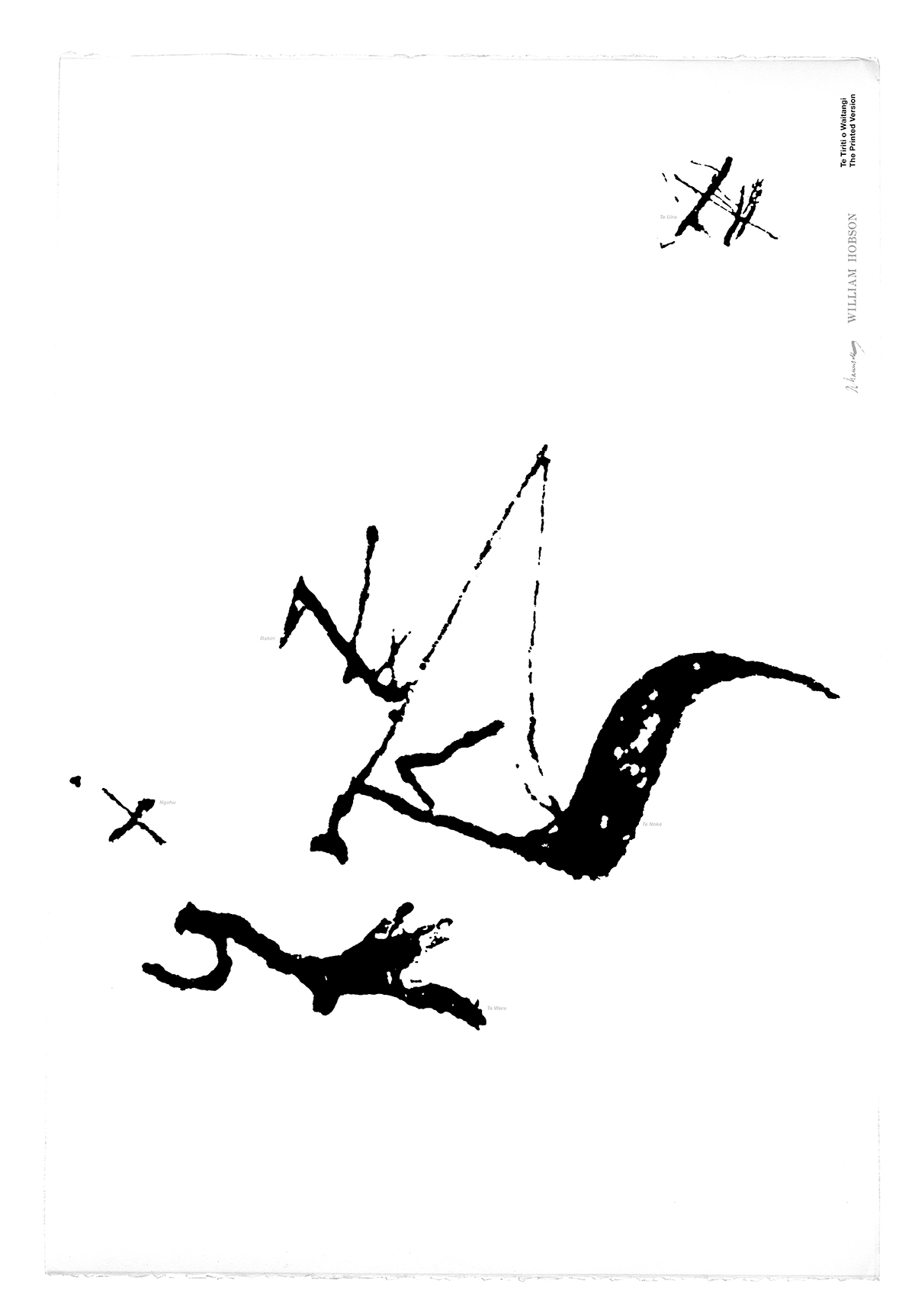

Actually, Max’s full project consists of ten large screen-printed sheets4—each one based on the original ten sheets that make up New Zealand’s two founding documents. The first document (and let's say the first single sheet [see above]) in Max’s series is from The Declaration of Independence.The second document is the Treaty of Waitangi that consists of nine sheets.5

As well as the brief historical background offered in these articles, Hailstone proposed possibly the most interesting and complicated issue implied by the project: the issue of the conflict or difference in status of the written word (and in particular writing of ‘signatures’) between Maori and English. The majority of chiefs were apparently “almost exclusively” illiterate:

When the Europeans arrived [in New Zealand] they found the Maori to have a culture which relied almost exclusively upon an oral tradition rather than one based on the written word. Their visual language, adequate for its purpose, was nevertheless extremely limited. Because of this lack of writing, being asked to ‘write a mark on a piece of parchment’ thereby pledging one’s allegiance to a ‘Queen’ on the other side of the world may well have been for many chiefs their first encounter with a pen. They certainly were unaware of the binding properties and degree of commitment that was the underlying cultural agreement signalled by their signature.6

So, although the comment about Maori visual language being “extremely limited” may not be well informed, the problematisation of the shared understanding in this exchange between an oral and a written culture is to the point. Maori were obviously not used to signing documents. Hailstone goes on to speculate that the closest thing Maori had to a written language was in the “visual language” of marks made for their moko (facial tattoo). This analogy is I think specious, and it is probably also going too far when Max explains that Maori moko marks (considering their form and placement within “strict divisions” on the face) were conventional, “universal” and as such “decipherable by all” as indicative of a person’s identity, importance, and lineage, marital status etc.7 These assertions are questionable (now and twenty years ago) and would no doubt raise the eyebrows of any post-colonial theorist. Such fixing and essentialising of the meaning of cultural practices and artefacts (like Maori moko) especially by oral cultures has proved to be suspect when it does not adequately account for how much meaning can change with context and how the meaning of something is activated through the performance of speaking about it. Max’s abstraction of and apparent amplification of the signatures as exotic primitive marks was also criticised by the art community at the time.

Art New Zealand

From an art perspective, Hailstone was criticised because he seemed content to treat the signatures of the ostensibly illiterate Maori chiefs as exotic marks. This was seen as an empty extension of the western primitivist art tradition. Painters have (and still do) get away with such abstraction, and there is a long history of NZ artist’s abstracting Maori motifs. But in contrast to Hailstone’s case, the history and meaning of the formalist project in painting are ultimately about abstracting from the art world itself.8

When I wrote that I was influenced by an article by Jonathan Mane-Wheoki about the project in Art New Zealand in 1991.9 As lecturer in Art History at the University, and a colleague of Max’s, Mane-Wheoki was closely involved in the project. I’m pretty sure he was at the tapu-raising that September. Mane-Wheoki’s critique in Art New Zealand was broader than from just an art perspective, it was also from a Maori academic perspective. So I want to quote from the article a bit more directly. This is pretty much the whole opening paragraph:

When it became known… that Max Hailstone… was preparing as his contribution to New Zealand’s sesquicentenary commemoration, large-scale screen prints incorporating the ‘signatures’ on the Treaty of Waitangi, alarm bells started to ring in the local Maori academic community. The marks were sacred: by what right had the artist appropriated them? Had the permission of those descendants whose ancestors the signatures, moko and crosses represented been sought, and an appropriate ritual clearance obtained? … It was clear that expert advice was needed as to the most appropriate way of releasing Hailstone’s work for public viewing, and to minimise the risk of a denunciation of the artist for seeking guidance, almost as an afterthought, when Maori etiquette requires consultation right from the outset in projects of this kind.

Also:

When full-scale mock-ups were produced at the monthly meeting of Te Runaka ki Otautahi o Kai Tahu (the Christchurch Maori Council), one delegate declared that according to the kawa of her iwi such taonga were not permitted to be displayed in the presence of women until the tapu had been subdued, and that she was obliged to withdraw from the meeting forthwith… However, the threatened departure was averted when the images were immediately removed to an anteroom by the artist, accompanied by a kaumatua and a tohunga and there, in a typically gracious gesture on the part of the mana whenua, the decision was arrived at to release the works by means of a dawn ceremony.10

From a Maori perspective, Hailstone’s project was seen as an unsanctioned appropriation of their sacred artifacts. Rather than being embraced as an expression of reverence and respect to the Treaty, an offering for "celebrating the event"11 from the realm of graphic design, their reproduction was seen as a mundane bromide at best and a profane travesty at worst.

An Illustrated History of the Treaty of Waitangi

The project quickly developed into another case of what looked like an unfortunate and insensitive cultural exchange between the English and the Maori… The tapu-raising was necessary to resolve the stand-off between Hailstone and the Maori community. It was a public demonstration against Max’s breach and was an attempt to repair or purify that which had been violated. This was a necessary ritual of giving back. It returned the aura to the document and re-asserted the sacredness of the Treaty document.12

There is of course a lot more to this historically too. The story needs to be understood in the context of the paticular moment in New Zealand and Maori history that was the late nineteen-eighties. The 1990s celebrations can be seen as the end of a chapter of at least fifteen years of tumultuous economic and political unrest, negotiation and protest—with race relations and Treaty issues at front and centre. In her book An Illustrated History of the Treaty of Waitangi, Claudia Orange titles the years leading up to 1990 as ‘The Roller Coaster Years – 1987 to 1990’. But the chapter before that from 1975 onwards could be seen as an extended period that set the scene for the reception of Max’s project. It is very hard to briefly sum up this history here—such a complex mixing and shifting of political, economic, cultural, and philosophical priorities can’t be easily distilled. But I want to index some fragments of evidence of the increasing political significance (and public awareness) of the terms of the Treaty contract as the foundation for real change in New Zealand society. So from the chapter ‘New Departures – 1975 to 1987’ by Claudia Orange:13

A new phase in the Treaty’s history began with the passing of the Treaty of Waitangi Act in October 1975…

The 1975 land march, or hikoi, began in Te Hapua in the far north and ended in Wellington… The march was a dramatic expression of Maori discontent over loss of land and of determination to part with no more. The march coincided with the passage of the Treaty of Waitangi Bill through its last stages…

The stands Maori took over land disputes at Auckland’s Bastion Point in 1977–78 and at Raglan in 1978 were emphatic and challenging. And in 1979, Matiu Rata resigned from the Labour Party and set up the Mana Motuhake Party, aimed at self-determination for the Maori people within the existing framework of government…

The demand of the modern protest groups was initially for greater Pakeha awareness and acceptance of Maoritanga—the whole complex of Maori culture and identity—which they claimed the Treaty had guaranteed. By 1980, the cry was for recognition of the Maori people as tangata whenua, the people of the land, and for an end to the loss of land from Maori ownership…

Debate and protest had an impact in the political arena as well. Labour in opposition was eager for Maori support, and hoped to give Maori concerns a fairer hearing. Announcing its Treaty policy in February 1984, Labour promised (if elected) to look into unsatisfactory Waitangi day ‘celebrations’, to consider incorporating the Treaty into a proposed Bill of Rights, and to extend the Tribunal’s mandate to cover grievances arising since 1840. The promise was repeated before the snap election of July 1984, which Labour won…

Following the [Treaty of Waitangi Tribunal] report’s recommendations, the Maori Language Act 1987 recognised Maori as an official language…

On gaining office in 1984, Labour had set out to restructure the economy in order to promote efficiency and growth, sooner or later, this aim was bound to clash with its commitment to resolving Treaty claims, which usually involved the return of land… In its proposed reforms, the state was preparing to relinquish the very resources it might use for remedy, and Maori feared there would be no land to return... The crunch came when the State-Owned Enterprises (SOE) Bill was introduced into parliament at the end of September in 1986…

The Muriwhenua claim 1986…

The Court of Appeal case 1987…

The Treaty of Waitangi (State Enterprises) Act 1988…

Maori Fisheries Act 1989…

Crown Forest Assets Act 1989…

Education Act 1989…

All of this merely hints at the massive political, legislative and street-level change in New Zealand society over that time, in particular concerning the position and rights of Maori. In what might now be seen as the beginning of a Maori Renaissance, the most significant changes over this time were to do with the shifting sense of ownership that Maori had—not just of land, but also more significantly in the repatriation of their culture. To quote from Jonathan Mane-Wheoki again, this time from a speech at the International Council of Museums conference in Christchurch in 2000:14

The Treaty of Waitangi Act, 1975, recognises that in the New Zealand nation’s founding document are grounded political, legal and moral imperatives. The Act provides the means by which grievances of long-standing [period] can be rectified—if only in part. In the extraordinary resurgence of Maori nationalism and culture there has been a determined push to reclaim land, reclaim resources, reclaim identity, reclaim self-respect and reclaim culture and cultural ownership. And ensure cultural integrity. Cultural ownership in this context means: ownership of land and resources, ownership of cultural treasures, ownership of their stories and histories and the language in which they are related, ownership of their cultural meanings and spiritual significance, ownership of the cultural systems and institutions, of their own world view.

In light of this, Max’s lack of sensitivity in approach, or plain naïveté towards expected protocols required to gain the necessary support from Maori for the project was not well timed in 1990. Maori were increasingly demanding consultation on issues relating to their land, taonga, history etc., and as a natural extension of this, were reclaiming ownership of the icon (or should that be index) for the main recourse to settle such claims, the Treaty document itself. However. The root of Max’s cultural mistake here (and why Max felt a bit bemused by the negative response to his project), was that he thought he could separate his project from the larger discourses of the society that he was presenting it to.15 Because I think in Max’s opinion, what he was doing, his approach, was too objective to be prejudiced, and too neutral/rational to be racially insensitive. In his mind the observational method of examining artefacts firsthand——abstracted from the messy contexts of any social sphere——insulated him from accusations of insensitivity or cultural bias. When of course on the contrary, many would argue that this logical empiricist methodology is itself inescapably culturally partial.

Visible Language Again

Part of Max’s conceit for the re-presentation of the original sheets was so that they could be “explored in terms of the Maori chief’s signatures and their significance in European and tribal custom.”16 It is worth stressing that this was for Max a sincere primary aim: to promote the signatures/signatories rather than the dominant elements of the original documents: the written terms of the Treaty and the English translation of chief’s names. Max explains in Visible Language how part of the prompt for him doing the project was from seeing a student of his working on a project concerning the Ngai Tahu land claim which was being heard by the Waitangi tribunal (and which was settled in 1990):

Because of the intense interest surrounding the Tribunal and its judgements, much discussion and argument was taking place concerning the wording and intention of these documents in very cool, legal and political terms. This cool approach seemed to forget that first and foremost the Treaty was a document of the people—drawn up by people and agreed to by people and signed in good faith for future generations—it was more of a spiritual guideline than a clinically legal undertaking. It was with this in mind that I decided to reproduce the Treaty from ‘the other side’ as it were, dealing with the people and their signatures without which there would be no validity to the document whatsoever. This approach forces the viewer to become involved with the people and their very human contribution.17

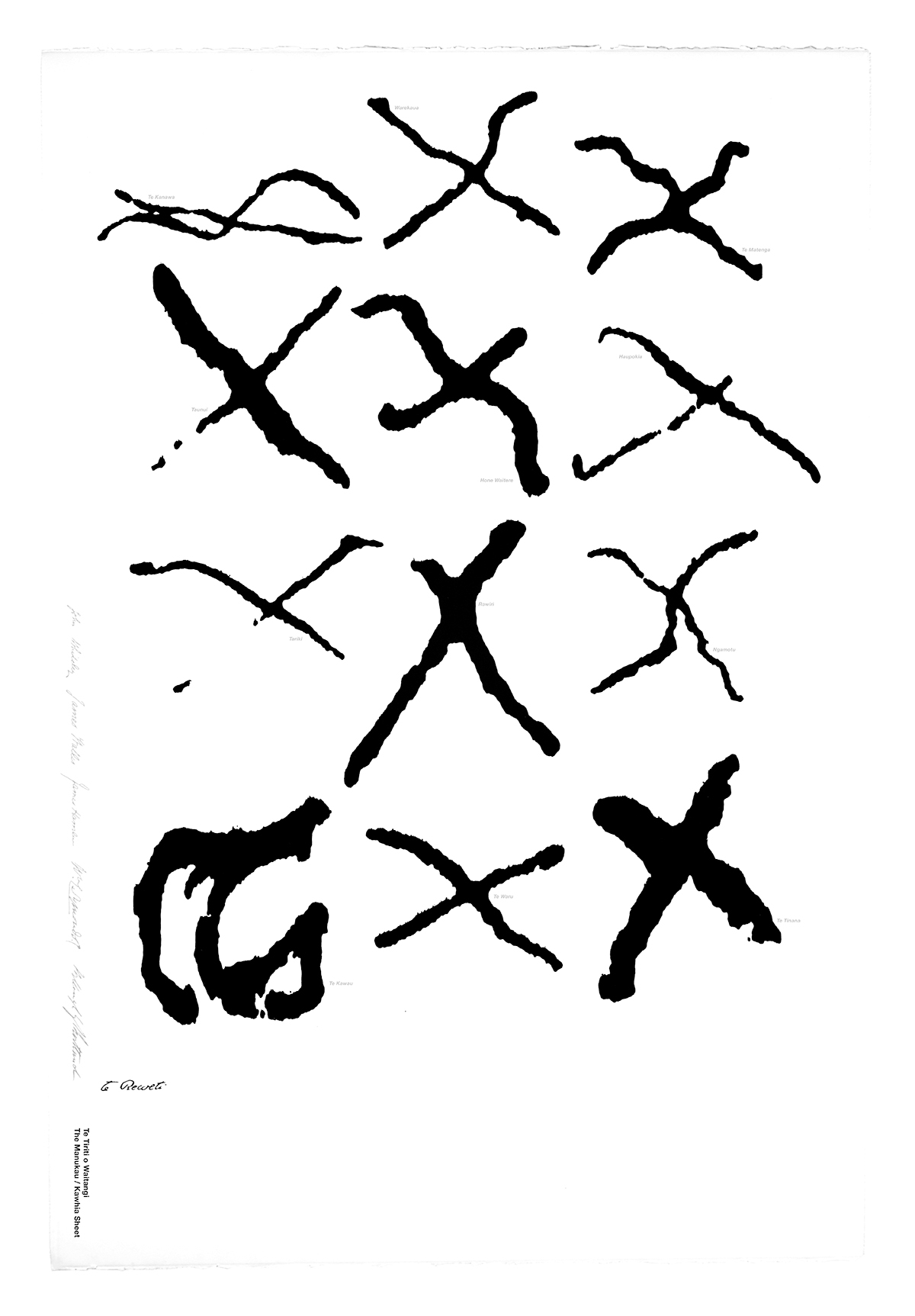

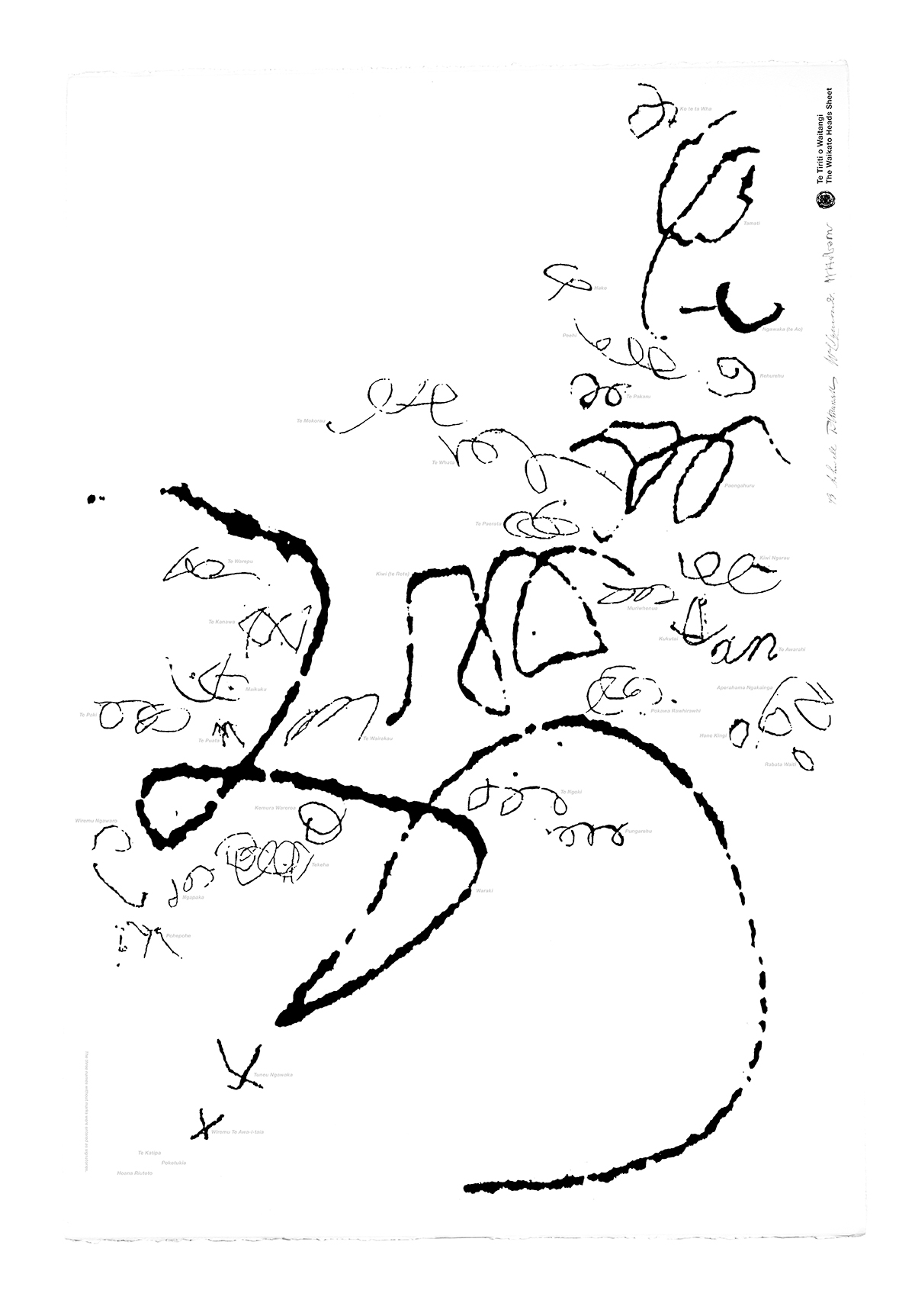

In both the Visible Language and TM articles Max explained that from his observation each of the eight regional sheets seem to have a different dominant style of mark. So for example the Manukau/Kawhia sheet (see below) is the “simple cross” sheet, and the Cook Strait sheet (see below) is the “fake signature” sheet. Max categorises the signatures into four types:

First, there are the ‘pictorial’ or figurative marks which owe much to the spiral of the fern frond almost certainly representative of a part of a particular chief’s moko…

Second, there are simple crosses which were obviously demonstrated and encouraged by the European representatives at the various signings… Third, there are quasi or ‘fake’ signatures which were obviously modeled on that of Hobson whose signature appeared on the Treaty prior to the Maori chiefs signing…

Finally, there are true European-style signatures which were made by those chiefs who had been in contact with the missionaries and administrators and who had been taught to write their names using the Roman alphabet.18

This is possibly an example of Max wishing to impose an essentialist, empiricist interpretation of the Treaty sheets extrapolated from probably fairly shallow personal observation:

Since there was no written tradition, it is likely that whichever chief first signed the respective copy of the Treaty, set the precedent for the others present who would not wish to lose face——hence the almost total agreement in terms of style and image used in each sheet.19

As well as the foregrounding of the signatories, and presumably as a result of the signatures being enlarged “in order to better examine their form and study their inter-relationships”,20 Max goes on to explain that from his exploration “small interesting details came to light”.21 For example: contrary to widely held belief, a handful of signatures were made by women; to one signature, “a man alone” was appended, indicating that the chief had signed without the support of his tribe; Te Rauparaha signed on two sheets; and in the time that it took to sign the seven copies of the original treaty, Governor Hobson’s signature rapidly deteriorated as a result of Parkinson’s disease. Because of this essentially synchronic exploration and re-presentation—abstraction, re-grouping, simplification and re-ordering—of the visual components of the documents, it might help to consider the project in reference to the graphic design tradition of information design or formal system design. Two sheets in particular (the “cross” sheet and “fake signature” sheet) hint at a straightforward typological indexing of marks.22 However, this ordering is contradicted in other sheets where Max seemingly randomly—but probably just more intentionally playfully—makes changes in position and size in what looks like one of Max’s classic student composition exercises. So if the impetus for the project was from a desire to “explore”, abstract and elucidate the visual language of the original documents, this looseness of placement and scaling of signatures is a bit vexatious:

The next stage was to assemble and organise the signatures from each sheet. All decisions concerning the differences in size were made with two main considerations in mind: either marks that were found to be more ‘interesting’, or marks that were considered to be more useful in compositional terms were enlarged. There is no difference inferred in terms of importance by the difference in size...23

This does need a bit more examination. Because although it may seem random, and in a cultural/historical context possibly offensive to make decisions of composition based on personal ‘interest’, Max’s compositional play does have precedents in graphic design. The project makes more sense if you acknowledge that Max was an English graphic design academic who was speaking for and who’s points of reference were from the canon of Modernist Western typo-graphic design.24 And even more specifically (for Max at that time), influenced by the Basel School of Design (Switzerland) and the Rhode Island School of Design (USA).25 Anyone who has any familiarity with these schools will recognise Max’s simplification of form, activation of counterform, intentional articulation of groupings and hierarchy, and knowing compositional play as being in the company of Armin Hoffman, Wolfgang Weingart, Malcolm Grear, and maybe Adrian Frutiger et al. So further to this, rather than being seen as an extension of the purely visual or primitivist art tradition—I want to argue that it should really be seen more specifically as a continuation of graphic design’s co-option of the early modernist, avant-garde project of ‘experimental typography’ by people like F. T. Marinetti, G. Apollinaire and I. Zdanevich associated with the movements of Dada and Futurism, etc. The aim of this project was to explore the material quality of the written word, and was as much rooted in the Literary art tradition as it is the Visual arts.26

Treaty Facsimiles

However, an alternative approach to the project, for comparison, would have been for Max to simply and technically perfectly reproduce (maybe just enlarge) the original documents as artifactual, archival reproductions. I propose this comparison because Max’s project does also need to be seen alongside the set of Treaty Facsimile27 reproductions (a project initiated by the New Zealand Government Printing Office) that did precisely this. Also because, coincidentally (but obviously not by chance), the third reproduction in this series of Treaty facsimiles was also published in 1990.

… Hailstone’s project could have been interpreted (but never really was) … from a graphic design or printing perspective. Max was, after all, a graphic designer. From this perspective, the project could have been seen as a continuation of the series of Treaty facsimile reproductions first published in 1877… The first set of very early photolithographs, made by the New Zealand Government Printing Office, still exist. There have been two subsequent re-prints of these facsimiles—in 1976 and in 1990. The interesting thing about these facsimiles is that they are now the documents that attest most faithfully to the visual content of the original documents. The real artefacts have deteriorated and faded so much that many signatures are now lost. It was in fact from the facsimiles, not the original artefacts, that Max was able to extract the signatures for this project.28

Max wrote in Visible Language: “Sixteen years ago my own interest in these marks was piqued, when I first came across a set of facsimiles of the Treaty.”29 It could be argued that the link to these facsimiles puts Max’s project within the context of the more politically neutral realm of historical archiving, reproduction and printing. This is from the ‘Introductory Note’ to the re-printing of the Facsimiles in 1976 by C. R. H. Taylor (the Chief Librarian, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington):

The Treaty was, and still is, important to the Maori for its affirmations concerning land, among other things. It is doubtful if it was meant as a legal document, for its authors—Governor William Hobson and James Busby—knew that only the simplest and clearest ideas could be understood by a native people with no experience of a civilised legal code. The Treaty was translated with considerable care by the Rev. Henry Williams and finally written out by the Rev. Richard Taylor, also no mean Maori scholar. It is likely that it was reasonably well understood by the usually highly intelligent Maori chiefs who signed it…30

Taylor’s statement that Hobson and Busby “knew that only the simplest and clearest ideas could be understood by a native people with no experience of a civilised legal code”, is interesting here. It echoes Max’s observation that Maori were a culture that used oral and visual language, but not written language. There is a note to that in the Visible Language text that also echoes Taylor, and suggests that by the time of the signing of the Treaty, Maori had begun to “embrace” the English written language. It reads:

The Maori were a highly intelligent race and soon embraced the idea of reading and writing. William Colenso, New Zealand’s first printer, produced many religious publications for the missionaries, using an alphabet of nineteen characters, five vowels and fourteen consonants.31

Although it may sound a bit patronising in tone, if we ignore the first bit, it is worth noting that this passage is if not inspired by, then thoroughly problematised by D. F. McKenzie’s book Oral Culture, Literacy & Print in Early New Zealand: the Treaty of Waitangi published in 1985.

Oral Culture, Literacy & Print in early New Zealand: the Treaty of Waitangi

McKenzie’s book is about the devastating effect that the introduction of the ‘technology’ of literacy had on Maori culture. But it is also about the British deficiency in understanding of their (lack of) success in converting Maori from an oral to a literate culture at the time of the signing of the Treaty. McKenzie explains the efforts by mostly British missionaries to teach reading and writing to Maori, focussing in particular on the two decades before the signing of the Treaty:

In New Zealand the twenty years or so immediately preceding 1840 span the movement from orality, through manuscript literacy, to the introduction of printing. In a minor way therefore they replicate in a specific and largely quantifiable context the Gutenberg revolution in fifteenth-century Europe. In that New Zealand context one significant document, the Treaty of Waitangi, witnesses to a quite remarkable moment in the contact between representatives of a literate European culture and those of a wholly oral indigenous one. It can be used as a test case for measuring the impact of literacy and the influence of print in the 1830s; and it offers a prime example of European assumptions about the comprehension, status and binding power of written statements and written consent on the one hand as against the flexible accommodations of oral consensus on the other. Its variant versions, its range of ‘signatures’, and the conflicting views of its meaning and status bring all those questions sharply into focus.32

And…

Twenty-five years earlier, the indigenous New Zealanders had been completely illiterate. They were a Neolithic race with a wholly oral culture and their own body of myths. Not one of their myths, however, was as absurd as the European myth of the technologies of literacy and print as agents of change and the missionaries’ conviction that what took Europe over two millennia to accomplish could be achieved—had been achieved—in New Zealand in a mere twenty-five years: the reduction of speech to alphabetic forms, an ability to read and write them, a readiness to shift from memory to written record, to accept a signature as a sign of full comprehension and legal commitment, to surrender the relativities of time, place and person in an oral culture to the presumed fixities of the written or printed word.33

McKenzie’s detailed thesis can be crudely summarised as spanning from initial (c. 1830s) British accounts of “enthusiastic reports back to London of the remarkable desire of the Maori to learn to read…” to (by the 1840s) a situation where “The presumed wide-spread, high-level literacy of the Maori in the 1830s is a chimera, a fantasy creation of the European mind. Even at Waitangi the settlement was premised on the assumption that it was, for the Maori an oral-aural occasion.”34

Conclusion

The seductive quality of Max’s Treaty Project was in its formal elements. But the fate of his project proved that when graphic design has pretensions to be about more, formal elegance isn’t really enough.35

When I wrote that I wanted to acknowledge that graphic designers do need to see what they do in a larger social context. It is hard to counter the criticisms from the Maori community regarding Max’s lack of consultation during the development of the project. And I am in a sense using Max’s project to illustrate that point. The point that graphic design only really makes sense as a kind of in-between discipline in the service of other disciplines.36 But I also want to counter this post-modern aphorism a bit (actually not so much counter as put it to one side). And this is where I am most conflicted, because I’m not really sure if this is possible now-a-days but… I think graphic design should also be able to be appreciated (still critically) from within the sphere of graphic design—as graphic design by graphic designers. Anyone who has been a student of graphic design, and knows the (Western European) canon—cannot help but be struck by Max’s prints as New Zealand accented modern graphic design. They are beautiful and I want to say important in that (admittedly introverted) local context. Especially in comparison to the standard fodder that was being produced by the graphic design industry at the time here.

My point in saying this is partly to challenge or question why it appears that there was no one from (or no forum for) the local graphic design community to intelligently discuss or defend Max’s project. Why not? Maybe because the graphic design community here confused (or rejected) it as too much of an ‘art’ project. Why was it only written up in Art New Zealand? Perhaps because it didn’t look like the usual commercial advertising product design that was in local design magazines at the time. I want to propose that on the contrary, what Max was doing was an early example (not a flawless example, but an example) of practice-based graphic design research. And it is worth saying that this kind of project was notable in these terms twenty years ago, especially considering that the academic design community here is struggling to define or produce such research even now.

So then, having said that, I also want to step half a step backwards (back into a larger social sphere again)… and say that while he was being used as an example of cultural insensitivity by the Maori community in 1990, what history may have overlooked was that Max was trying to advance the culture of graphic design in the view of all of New Zealand. In a gesture that was (again) before its time here, by doing a design project on our founding documents, Max was trying (okay, also failing) to make an argument for graphic design as a player alongside the most important social and political discourses in New Zealand.

To sum up this study in cultural stake claiming then… and I need to get this right because I’m having trouble stopping it from sounding contradictory: Max was a Pakeha (English) graphic designer living in New Zealand, who was criticised by both the local Art and Maori communities on their terms——partly because he conceived of the project in narrowly modernist graphic design terms. But also his project was not defended by the local design (or printing) community, not judged on their terms at least. However, I also want to suggest, ironically perhaps, that what Max should be celebrated most for is trying to advance New Zealand graphic design as a player in a broader political and social cultural sphere. And that is the key bit for me, the bit that has unfortunately been forgotten along with Max’s project. Because despite the dawn tapu-raising ceremony, Max was forced to retreat with his project to the relatively politically neutral realm of international typographic design. And the remaining sheets37 are now hidden, crated up in a warehouse in Woolston in Christchurch.

Footnotes

‘The Weight of a Document’, The National Grid #1, Auckland: 2006. p.86. ↵

The Visible Language article appears to have been written later and has been re-ordered, edited and added to (the Typografische Monatsblätter (TM) article was from the first issue of 1993, Visible Language was published Summer 1993). ↵

Max Hailstone, Visible Language, vol. 27.3, ‘Te Tiriti’. Providence: Rhode Island School of Design, 1993. p.302. ↵

From TM: “The prints are printed in two colours (black and grey), silk screened on Arches Rives BKF 300, 1200 x 800mm in an edition of 20, of which 10 are reserved in complete portfolios of all nine (sic) prints.” Max Hailstone, Typografische Monatsblätter, Nr1:1993, ‘Te Tiriti’. St Gallen: Zollikofer AG, 1993. p.9. ↵

The Declaration of Independence, signed in 1835, is considered by some to be the real founding document of New Zealand. The first Treaty document was signed on one sheet on the 6th February 1840 in Waitangi. After this, seven replications of the Treaty were produced for the gathering of further support (and signatures) of Maori representatives in other regions of the country. The first eight Treaty sheets contained the terms of the Treaty “written in longhand” in Maori and English—and a final “printed version” was printed (by missionary printer William Colenso). ↵

Visible Language. vol. 27.3, 1993. p.305 ↵

In both articles, this is illustrated with images from Ko te Riria and David Simmons, Maori Tattoo. Auckland: The Bush Press, 1989. ↵

The National Grid #1. p.86. ↵

Jonathan Mane-Wheoki, Art New Zealand, No. 60, ‘Treaty Issues: Max Hailstone’s 1990 Project’. Auckland: Art New Zealand, 1991. ↵

Ibid. p.56. ↵

From the introductory abstract to article in Visible Language, vol. 27.3, 1993. p.302. ↵

The National Grid #1. p.86. ↵

Claudia Orange, An Illustrated History of the Treaty of Waitangi. Wellington: Bridget Williams Books, 2004. pp.142–175. ↵

From the conference address by Jonathan Mané-Wheoki, ‘Zero to 360 degrees: Cultural Ownership in a Post-European Age’, at the International Council of Museums, Council for Education and Cultural Action conference, University of Canterbury, New Zealand, 2000. From the Christchurch Art Gallery web site: http://www.christchurchartgallery.org.nz/icomceca2000/papers.shtml (accessed 6.3.2010). ↵

I’ve mentioned a few times that there were different interpretations of the project by different groups, or cultural spheres—Maori, art, history, etc. And this is kind of the crux of my essay. I am working on the assumption that there is no primary interpretation of the project. And when I say that, I am I guess subscribing to the modernist project of differentiating cultural spheres—and that is, from my limited sociological schooling, in reference to the writing of sociologist Scott Lash. So, in what is according to Scott Lash essentially the definition of Modernism: Max’s natural inclination was to differentiate the cultural sphere of ‘graphic design’ from ‘political’ and ‘social’ spheres. Or maybe stated more broadly: to separate the aesthetic from the real world. ↵

Visible Language, vol. 27.3, 1993. p.302. ↵

Ibid. p.307. Interestingly this was not in TM as it does add quite a lot to the story. ↵

Ibid. p.309. ↵

Ibid. p.309. ↵

Ibid p.302. ↵

Ibid. p.307. ↵

Incidentally, but I think also in support of this point, Max recorded a photographic essay and developed a schematic diagram presenting a typology of symbols/pictogrammes from the painted ‘Doors of Rajkot’ observed on a visit to India, and published it in Typografische Monatsblätter, Nr1:1990. ↵

Visible Language, vol. 27.3, 1993. p.311. ↵

Admittedly the 1990s was late to be so high-modernist. ↵

Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) and Canterbury University had an exchange programme for many years, and it probably doesn’t need to be pointed out that Visible Language was published by RISD. ↵

I am drawing from Johanna Drucker’s study of experimental typography in The Visible Word here. This book is about the work of writers and artists of the 1910s and 1920s whose typographic production, Drucker explains, was a tradition ‘in between’ or a synthesis of Art and Literary spheres. Johanna Drucker, The Visible Word: Experimental Typography and Modern Art, 1909–1923. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1994. ↵

Facsimiles of the Declaration of Independence and the Treaty of Waitangi. Wellington: New Zealand Government Printer, 1877, 1976, 1990. ↵

The National Grid #1. p.87. ↵

Visible Language, vol. 27.3, 1993. p.306. ↵

C. R. H. Taylor, Facsimiles, ‘Introductory Note’. Wellington: New Zealand Government Printer, 1976. p.1. ↵

Visible Language, vol. 27.3, 1993. p.311. ↵

D. F. McKenzie, Oral Culture, Literacy & Print in Early New Zealand: the Treaty of Waitangi. Wellington: Victoria University Press, 1985. p.9. ↵

Ibid. p.10. ↵

Ibid. p.35. ↵

The National Grid #1. p.89. ↵

This is partly a reference to Stuart Bailey from the article ‘Dear X’, in Dot Dot Dot 8. The Hague: Dot Dot Dot, 2004. p.3. He muses that graphic design “only exists when other subjects exist first. It isn’t an APRIORI discipline, but a GHOST; both a grey area and a meeting point—a contradiction in terms—or a node made visible only by plotting it through the lines of connections.” ↵

Actually that’s not entirely true, quite a number have been sold: for example to the Christchurch Art Gallery, The University of Canterbury Law School, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, and private collectors. In fact although there are quite a number of individual sheets left, there is only one full set. ↵