We're So Bored With London, Part II – Wayne Daly, Russell Bestley

Kids in the city say they're bored, but what about us in the sticks?

— Varicose Veins, 'Geographical Problem' (Warped Records), 1978

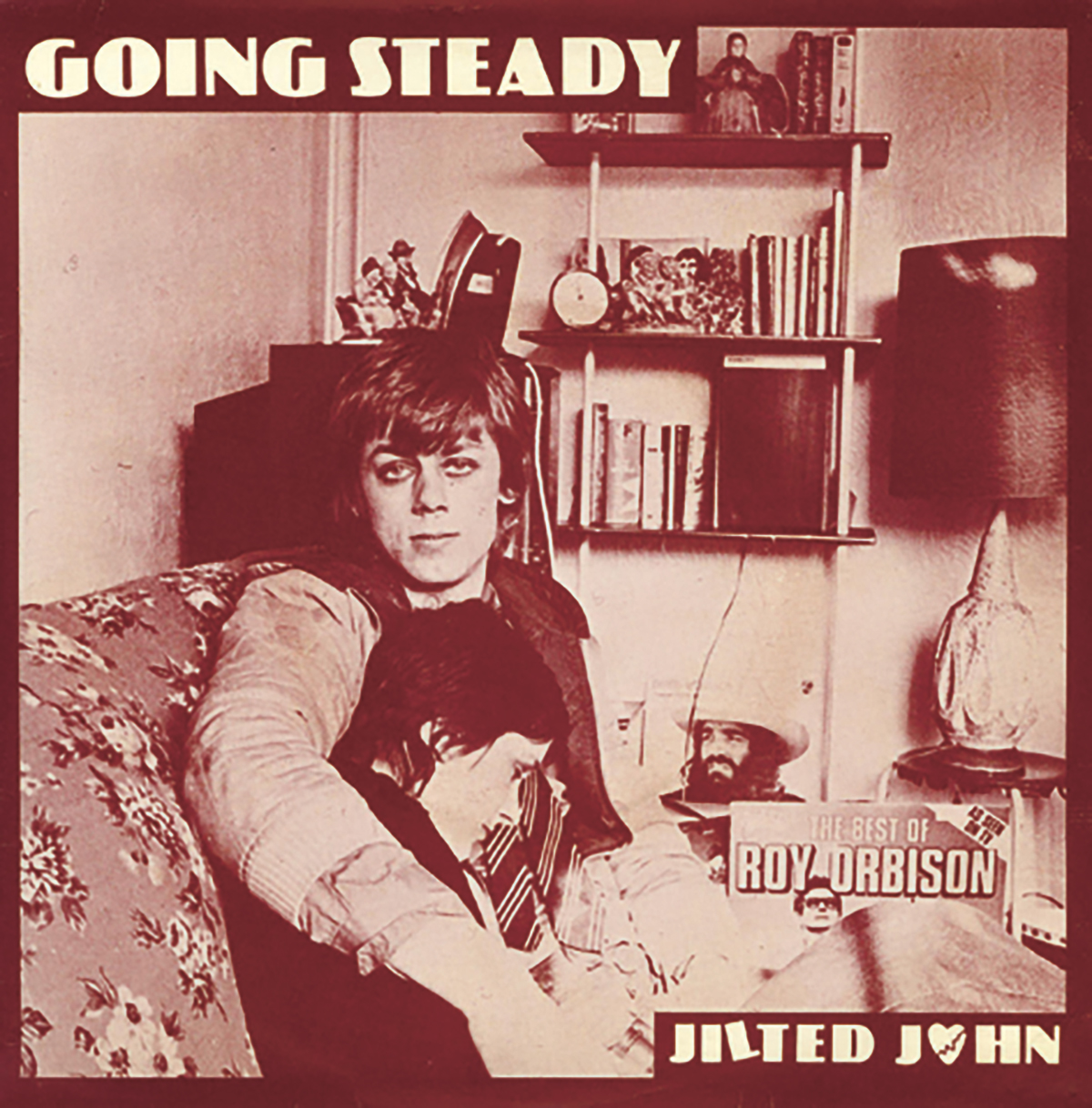

One aspect of punk culture that is often overshadowed by the political facets is the humour. The idea of 'novelty records' conjures up thoughts of poorly-judged Christmas singles, but it seems an entirely appropriate term for some pretty funny stuff like the Water Pistols' Gimme That Punk Junk. Graham Fellows' chart success in the guise of Jilted John indicates there was some kind of market out there. I guess in the DIY spirit, it seems like it was easy for anyone to join in and take the piss out of the genre (gently or otherwise), and in fact it could be quite self-deprecating. From the point of view of your research, I'm curious to know the extent to which these kinds of humorous regional 'voices' and idiosyncrasies are manifested in the sleeves and lyrics. And with this in mind, do you think punk is taken too seriously?

Punk is taken far too seriously! Actually, that statement presents something of a dichotomy for me—I am a lifelong follower of punk music, and I genuinely think it merits a 'serious' profile alongside say jazz or folk music, both of which have their own well established field of academic study and cultural dialogue. However, as a fan I also feel very protective towards the subculture' (even calling it that presents me with something of a problem), and I really don't want it colonised by outsiders and cultural theorists. My research often walks a tightrope between these opposing positions—I fully sympathise with punk fans who are deeply mistrustful towards academics researching their culture, but at the same time I see punk history as just as important as the histories of jazz and blues, the sixties folk revival, West Coast hippiedom etc.

Still, to answer your original question a little more succinctly, I think 'punk' has become stereotypically associated with protest, anger and vitriol, and this unfortunately belies the breadth and range of punk voices, at least in the UK. My next planned stage of research focuses on the notion of humour, particularly as evidenced within punk lyrics and graphic design. In fact, the closer you look, the more clear it becomes that humour is embedded across a wide range of UK punk, and is evident in the unlikeliest of places.

In some cases, such as the punk parodies of the Water Pistols, Alberto Y Lost Trios Paranoias, The Punkettes, Matt Black & The Doodlebugs, Jilted John, and The Monks, the comic 'voice' is up-front and self evident. Often, these examples were created by outsiders to the punk scene—cabaret and performance groups and comedians, as well as those wishing to cash in on a new trend with significant media interest. Even 1950s/60s comedian Charlie Drake got in on the act, releasing the comedy single Super Punk in late 1976, and many British comedians incorporated a punk sketch within their stage and television acts.

A second set of comic punk commentators came from within the subculture itself. Even early on in UK punk's development, groups such as Alternative TV, The Adverts, Television Personalities, and the O Level were passing critical comment on the way that the new wave was being co-opted by the media and fashion industries, and (in their eyes at least) mis-interpreted by new groups of stereotypical 'punks' and outsiders. The Television Personalities classic Where's Bill Grundy Now? EP included a comment on punk fashionistas in the song 'Posing At The Roundhouse', and on the ways in which bandwagon jumpers and trend followers were filtering into the scene in their most famous track, Part-Time Punks'.

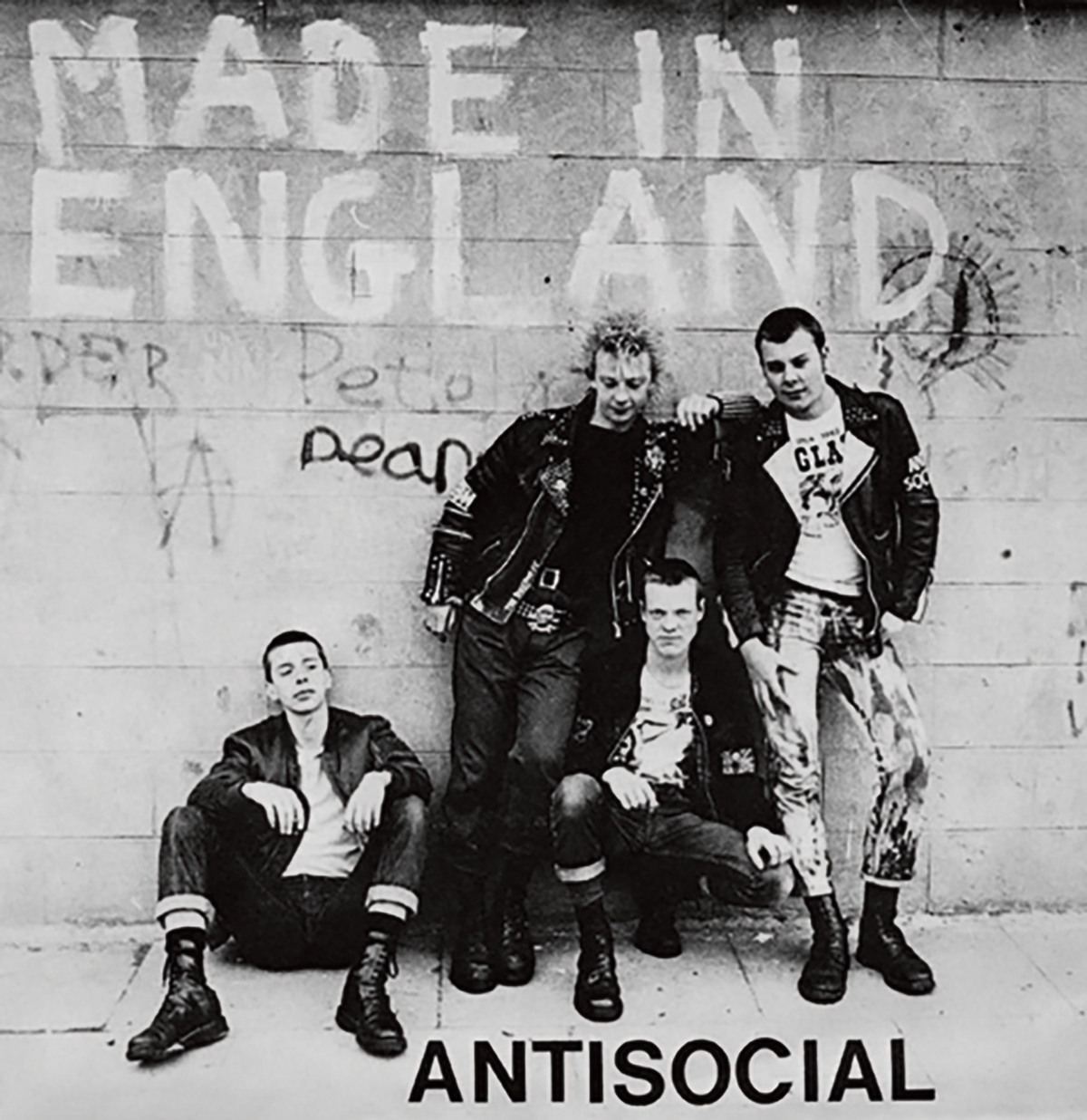

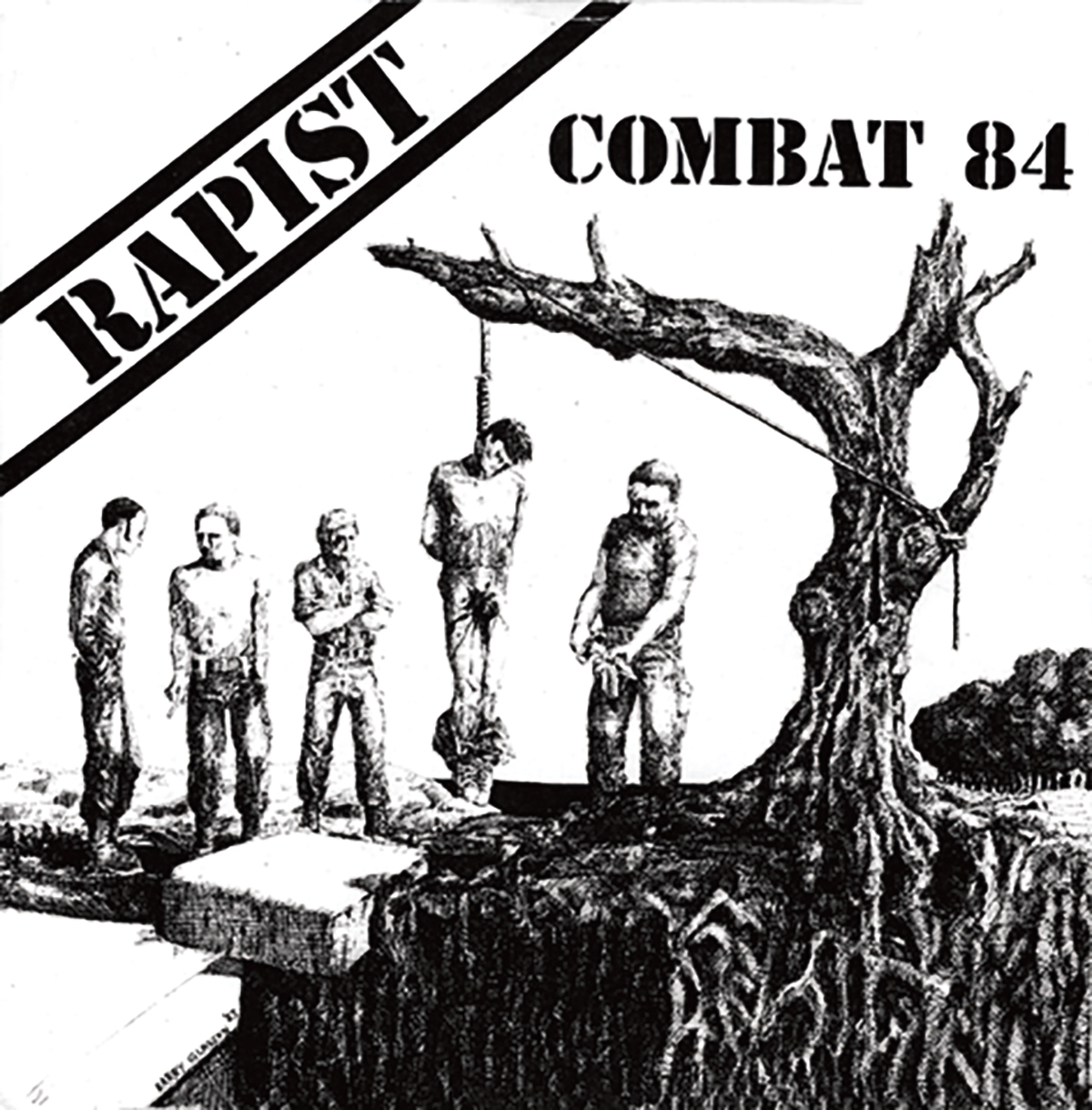

Interestingly, this kind of internal discourse within the punk movement carried on throughout the period I've been researching—many later Second Wave punk groups became quite obsessive about 'authenticity', and this was further developed during the early 1980s Third Wave. By then, punk had fragmented into a number of different, and sometimes opposing, factions and sub-genres: Anarcho Punk centred on the notion of anarchist politics voiced during the First Wave of UK punk (though, in their eyes, not followed through), while Hardcore and Real Punk focused on the original punk ideals as they saw them, of independence and protest. Authenticity was central to Oi, the crossover skinhead/punk movement of the early 1980s, and many groups voiced disgust at the 'poseurs' buying into the scene before moving on to another new trend. This can be seen through the lyrics of songs such as 'Poseur' by Combat 84 and Clockwork Skinhead' by the 4 Skins:

Wearing braces, the red, white, and blue

Doing what he thinks he ought to do

Used to be a punk and a mod too

Or is it just a phase he's going through?

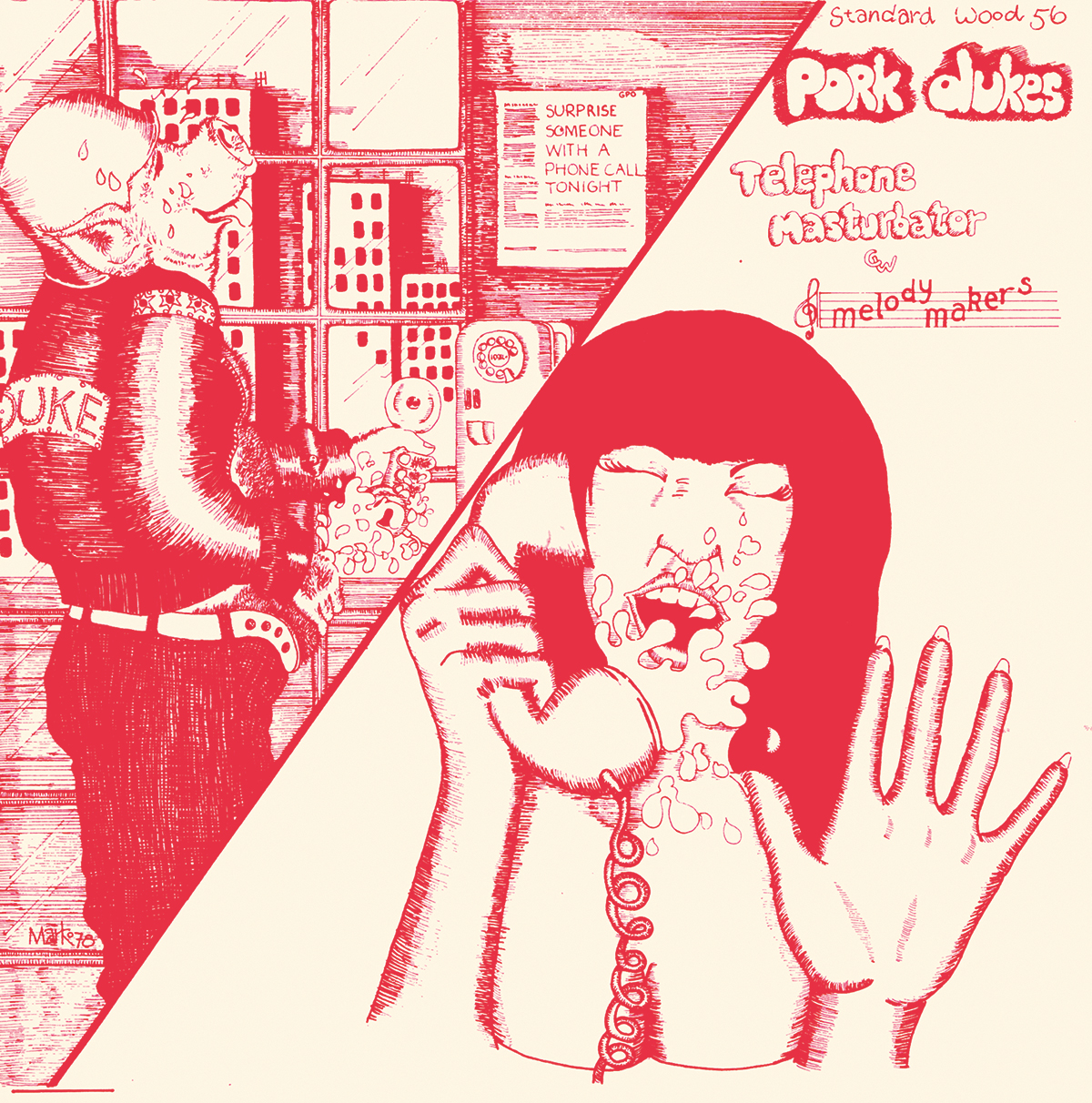

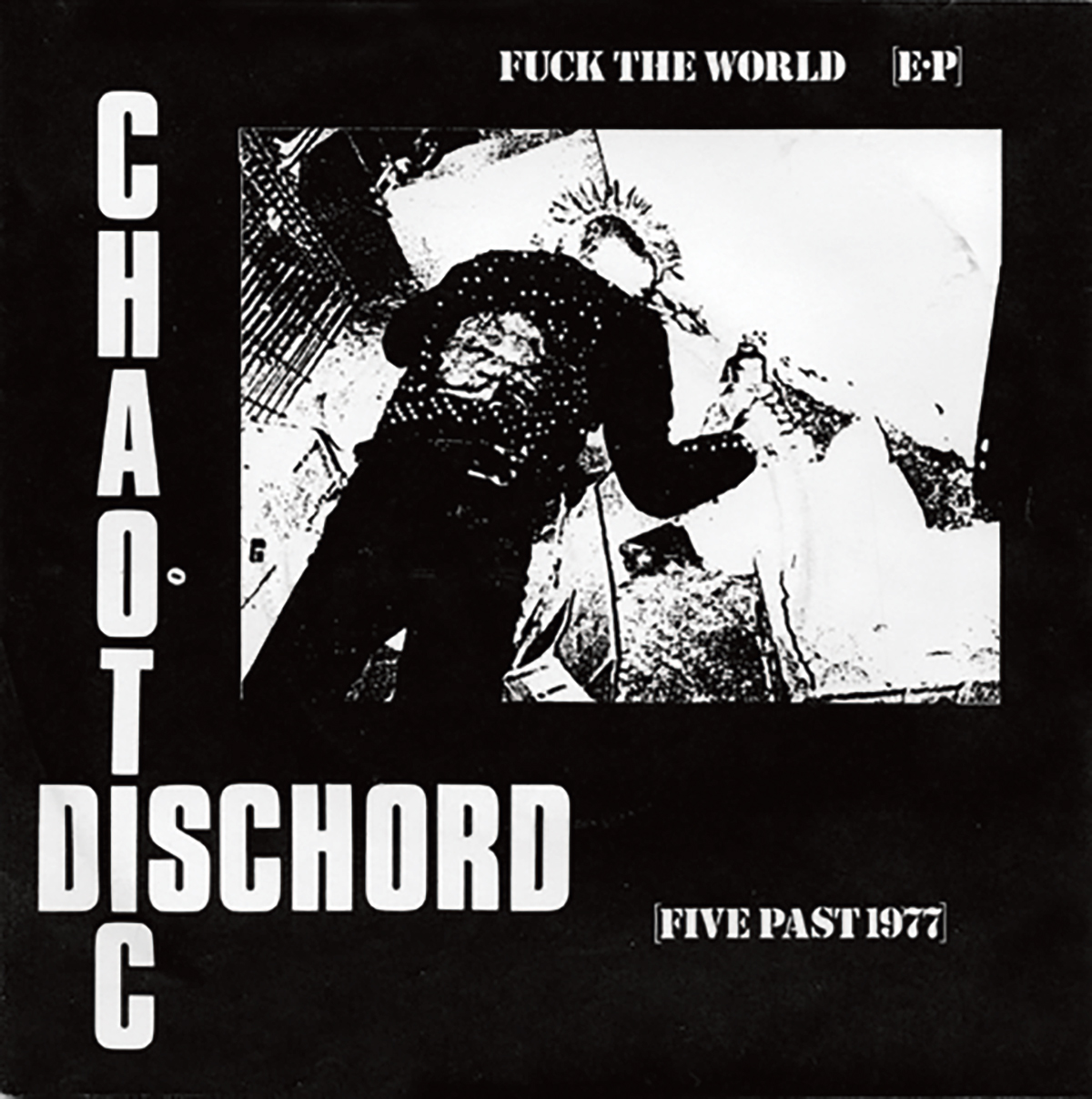

Some groups utlised this obsession with authenticity in an openly humourous way: Splodgenessabounds, Chaotic Dischord, the Anti-Nowhere League, and The Ejected wrote songs which commented on the punk scene and its internal dialogue in a clearly comic manner. The Anti-Nowhere League's visual demeanor, combined with songs such as 'I Hate... People' and 'Let's Break The Law', saw them adopt a cartoon punk identity which proved successful with punk audiences, though not with music press critics. Chaotic Dischord were a Hardcore/Thrash punk parody group from Bristol, formed as an incognito offshoot of successful New Punk group Vice Squad: their record releases included the debut Fuck The World EP (1982) and the album Fuck Religion, Fuck Politics, Fuck The Lot of You! (1983), and despite their obviously over-the-top and tongue in cheek offensiveness they went on to be successful in the independent record charts. In fact, the theme of punk groups adopting comically offensive approaches could be seen as a key underlying trait—The Pork Dukes had adopted similar tactics five years previously for their singles Bend And Flush and Telephone Masturbator.

However, beyond these groups and songs whose intention was to amuse their audience, humour was a far greater underlying theme across a lot of UK punk than often assumed.

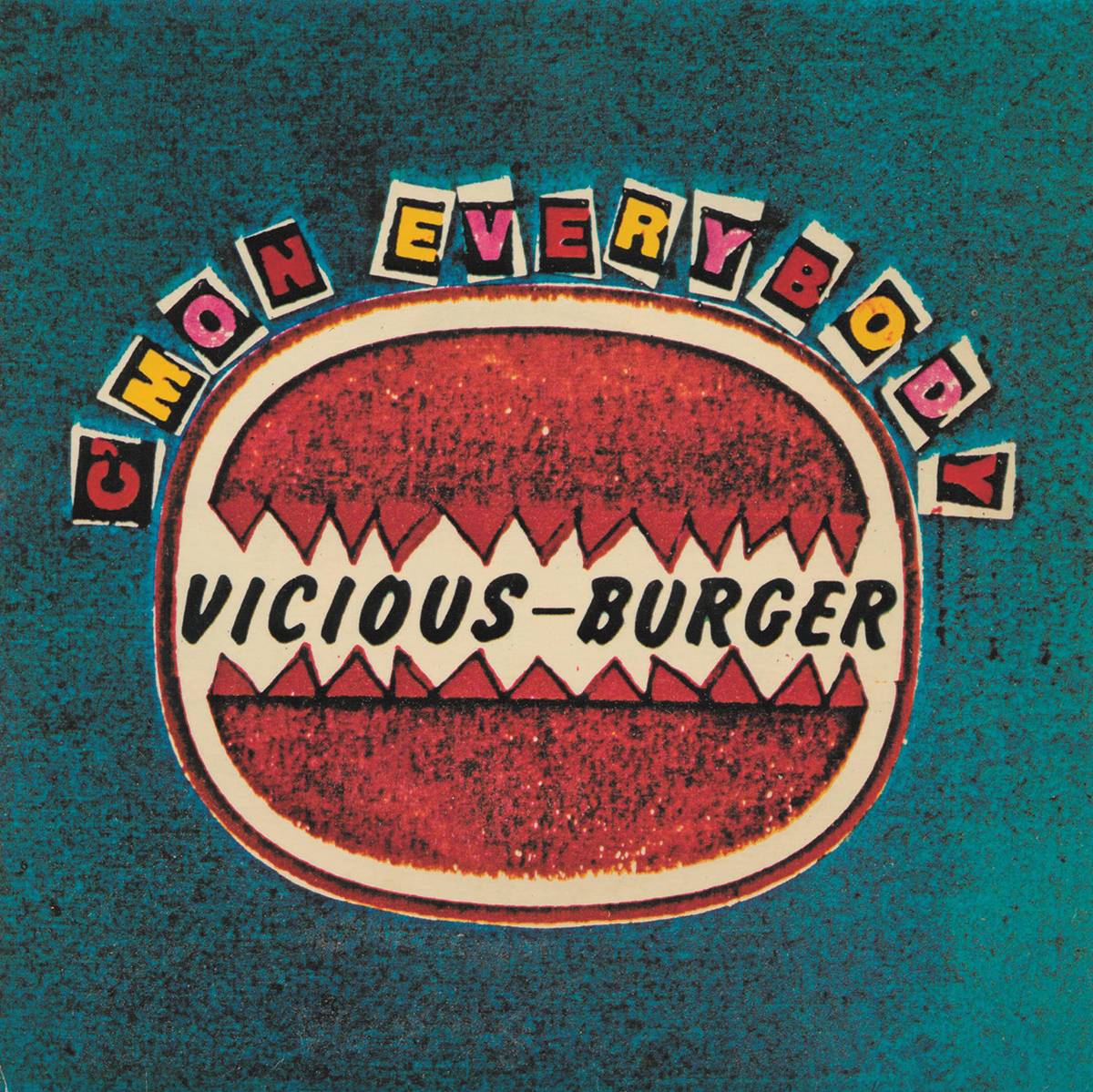

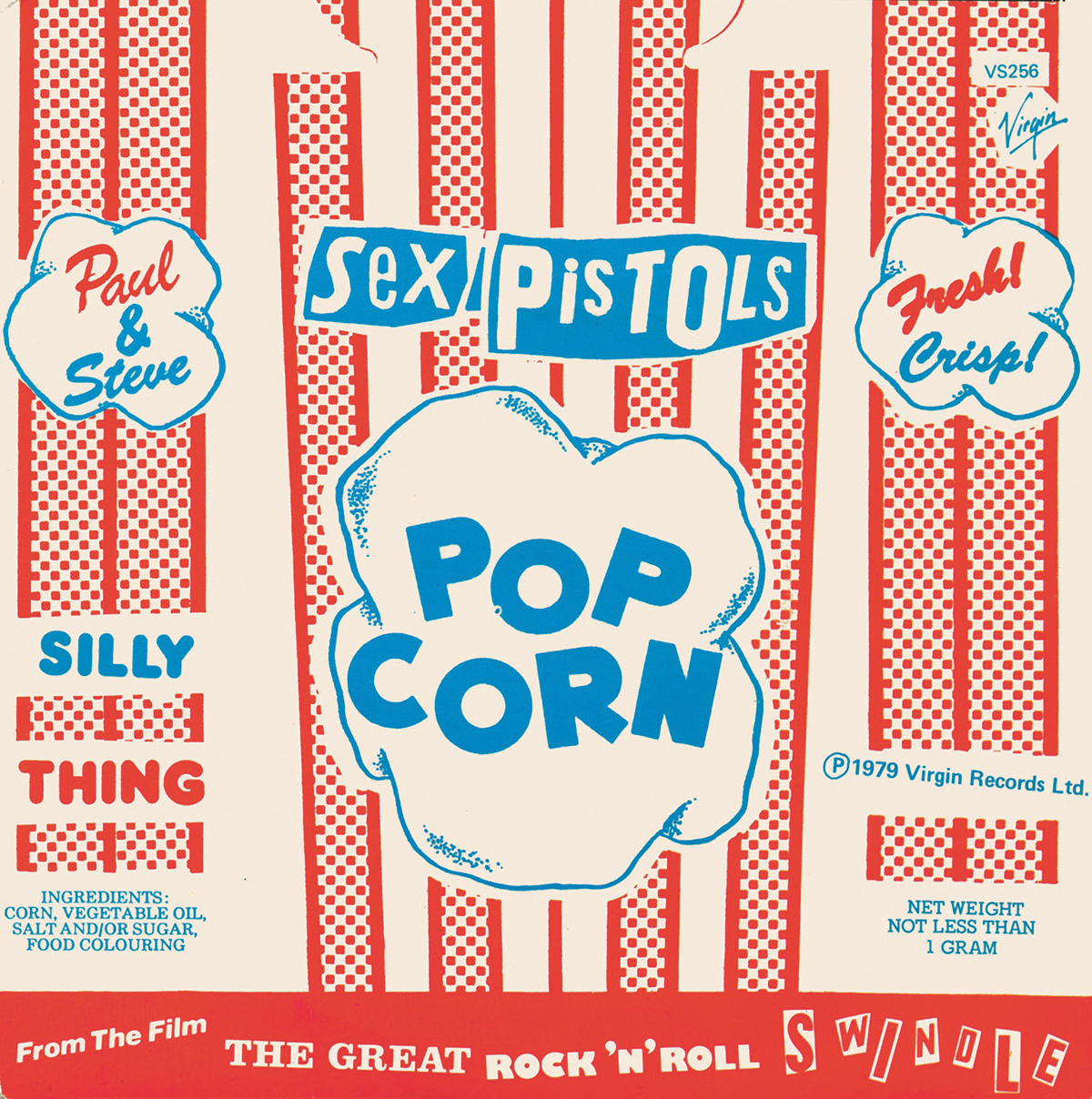

If you bring in themes of sarcasm, irony, parody and satire it covers most punk output in some way. The Adverts, Alternative TV and X Ray Spex commented directly on the growing punk scene in their songs—though it does have to be said that this is less evident in their record sleeve design. The Sex Pistols' lyrics were witty and sarcastic, rather than simply thuggish and aggressive, and Jamie Reid's sleeve designs followed suit. Reid's later work for the Sex Pistols was, in my opinion, some of his best: a strategy adopted by Reid, particularly during the later phase of the Sex Pistols' musical career and the filming of The Great Rock 'n' Roll Swindle, centred on the presentation of the group as a cynically marketed 'product', without any creative or artistic merit. The sleeves for a series of singles were designed to ram the point home: while some featured stills from the film itself, others such as Silly Thing and C'Mon Everybody (1979) featured examples of graphics developed for the fake products created by Reid as props for various scenes in the film. While Silly Thing featured 'Sex Pistols Popcorn' packaging, C'Mon Everybody had an image of a 'Vicious Burger' on the front of the sleeve. Other bogus products used in the film included 'Gob Ale', 'Piss Lemonade', 'Rotten Bar' chocolate and 'Anarkee-Ora' (a pun on Kia-Ora, a brand of soft drink often sold in cinemas). The full range of dummy packages were featured in a scene at a snack kiosk in a cinema foyer when audience members arrive to see the new Sex Pistols film, with veteran comic actress Irene Handl and singer Eddie Tenpole as ushers.

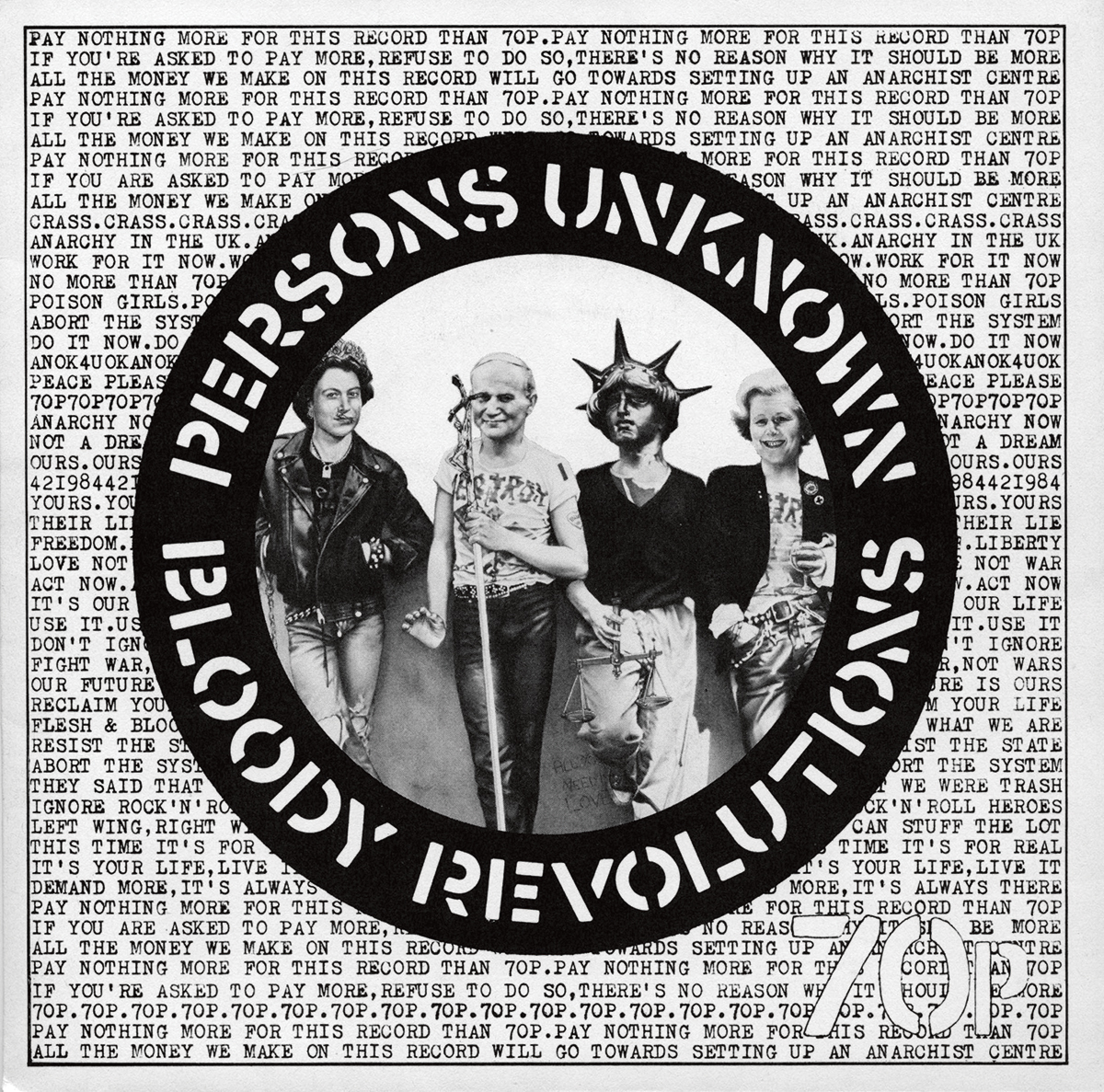

Similarly, even some of the most 'serious' of the later political Anarcho Punks, Crass and The Subhumans, embodied a sense of underlying wit in their record output, employing satirical humour in their lyrics as well as their sleeve designs. Crass also contributed to the punk authenticity debate with the sleeve to their second single, Bloody Revolutions, released in 1980. The image, a gouache illustration by Gee Vaucher, is based on a publicity photograph of the Sex Pistols from 1977, reconfigured with the individual's heads substituted by those of the Queen, Pope John Paul II, the statue of justice and Margaret Thatcher. This complex image works on a number of levels: primarily, it satirises the Sex Pistols themselves as figures of authority and the state, passing an ironic comment on their failure—and that of the punk 'establishment'—to live up to a 'revolutionary' ideal. However, the use of iconic individuals for the heads of the figures also works as a direct détournement of those icons themselves, within the context of a punk rock record. Crass strongly criticised the failure of the punk movement in general to engage with a political direction, satirising The Clash, the Sex Pistols and other punk 'heroes' in their lyrics, and this attitude was reflected in their early artwork.

As I have said previously, punk's adoption of an 'anyone can do it' philosophy led directly to widespread regional interpretations of the subculture. Regional voices were reflected in vocal styles and accents, in the locations of group photographs on record sleeves, and within the songwriter's lyrics. Humour often played a key part in getting that message across, whether it be a comment on suburban boredom (The Clash's 'The Prisoner', The Members' 'Sound Of The Suburbs', Buzzcocks' 'Running Free', The Skids' 'Sweet Suburbia'), or local government policy and the lack of venues for bands to play in their local areas (Special Duties' 'Colchester Council', Resistance 77's 'Nottingham Problem'). There was anger in many of these songs, but it was filtered through a satirical and sometimes ironic phrasing, sometimes combined with a kind of petulance and sardonic wit. As Anti-Nowhere League put it in the title track to their debut album, 'We Are The League', released by WXYZ Records in 1981:

We are the League and we are shit

But we're up here and we're doing it

So don't you criticise the things we do

'Cos no fucker pays to go and see you

So has the academic nature of your research presented any problems—have you encountered any mistrust?

I think 'mistrust' is a good word to use in this context. Many underground subcultural groups' are based on a strong sense of 'authenticity', and I think this applies to punk probably more than most others. Outsiders to the subculture—or those seen as outsiders at least—are often accused of trying to cash in on a fairly exclusive scene, or of having some kind of ulterior motive for becoming involved. Given the outwardly antagonistic and anti-authoritarian viewpoint expressed by many punk groups and fans, this sense of resentment isn't at all surprising, and academic investigations can also suffer from being seen as in some way pretentious, high-brow, middle class attempts at recuperation of what is often seen (from within) as a determinedly low-brow, anti-intellectual, working class culture.

Interestingly, early UK punk groups (and more especially their managers) flirted with the worlds of high art, fashion and 'culture' for a while, crossing over into art schools and galleries and therefore being to an extent in league with at least the artistic side of academia. Later on, as street punk and its variants became more prominent, the two worlds moved further apart once again. This comes back to an earlier discussion we had about provincial 'outsiders' coming into the London clique and getting it 'all wrong' (at least from the viewpoint of certain 'insiders' who had found a comfortable, and influential, space within that clique). Vivienne Westwood went on to become a perfect example of punk's crossover into the high fashion elite, but it is also interesting to note that many punks, especially what could be termed those in the Second Wave, rejected the idea of spending large amounts of money on 'designer' punk clothing, and were highly critical of any kind of overt commercialism, including expensive punk boutiques on the King's Road. This filtered down to the design and marketing of records, with more emphasis on lo-tech, black and white sleeves, a rejection of glossy production values, and a return to mass-produced, black vinyl records rather than limited edition coloured vinyl 'collectors' items.

The English obsession with class is incredibly important here: many punk fans came from lower middle or working class families, and the ways in which punk identified itself as 'real' and not 'fake', or a 'pose', were wrapped up in a kind of overt and confrontational class rhetoric. The language, coming from 'the street' and not 'manufactured' mirrored other youth subcultures, for instance the late Hippie underground, which also influenced the development of Pub Rock. Much Heavy Metal also characterised itself as a genuinely street-level phenomenon, with few pretensions to high art or culture, as did the skinhead revival of the late 1970s, and it's no surprise that there were strong connections and crossovers between these areas.

Much of the Third Wave of UK punk, as we have already discussed, was regional, and strongly influenced by younger, and often less culturally advantaged, groups. A number of interviews conducted by Ian Glasper for the Third Wave book Burning Britain: The History of UK Punk 1980–1984 centre on the perceived 'working class' nature of the 1980s Hardcore and New Punk movements. While certain arguments about class credibility and punk authenticity might be called into question, it is broadly true to say that many Third Wave groups and fans did voice a general opposition to what they termed the 'middle class' roots of earlier punk, and towards students in particular. Songs such as 'Student Wankers' by Peter & The Test Tube Babies and 'Are Students Safe?' by Chaotic Dischord display a certain antipathy towards their subject. With a widespread rise in un-employment in the early 1980s, particularly amongst the young working class, and an accompanying increase in the divide between rich and poor, the 'new Art School' optimism of the First Wave was largely replaced by the 'old dole queue' pessimism of the Third Wave.

Academic research into punk, whether it be based in cultural studies, history, or a study of the visual and musical 'voice' of the subculture, is bound to encounter some opposition, or at least a number of questions as to the motivation of the questioner. I have been quite lucky in many ways, in that I have been involved as a punk fan (and unsuccessful musician!) for many years, and I came to academia from within the subculture, not outside. As such, I can field many questions in relation to my own 'authenticity' and my longstanding interest in the subject. More punk histories have been written recently from within the subculture itself, and it isn't quite so unusual to see punk being analysed and written about by the likes of Alex Ogg, John Robb, Ian Glasper and Paul Marko, all of whom have a high level of trust within the scene. It is a fine line though, and I have often had to present a quick summary of my own intentions before any introduction to the actual questions I wish to ask. As I have also exhibited a lot of the visual material in large galleries and institutions (including the British Film Institute, Southampton Millais Gallery and the London College of Communication), and at the Rebellion punk festival in Blackpool and on the website, I have been very aware of the potential issues and conflicts between the punk underground, major cultural and educational institutions, and audiences both familiar and unfamiliar with either the material, or the notion of academic discourse in the area of popular culture.

You mentioned previously your decision to confine your research to a nine-year period (1976–84); is there a story to be told after the mid-eighties? Or to put it another way, is it possible to identify a point at which the movements which you're discussing began to become less significant after this time frame?

Yes, there is certainly a story to be told after the mid-eighties with regard to the development of whatever we might describe as the punk-related underground, as there is equally a history of what can be described as Proto Punk prior to 1976. However, my decision was in many ways pragmatic, and related not only to a decline and/or dissipation of the subculture, but to a distinct change in both formats and the technology involved in music packaging and distribution.

Many punk groups continued to record and perform throughout the 1980s and 1990s and indeed, a significant underground/DIY network continues to thrive, together with something of a revival circuit for older groups. There are, however, a number of factors for choosing to end this study at this point: the seven-inch single was in decline in the market from around 1982 onwards, particularly with the impact of the twelve-inch single as a widely adopted alternative format offering better sound quality and potentially longer playing times. The widespread shift to twelve-inch singles across other genres during the early 1980s did eventually have an impact on Third Wave punk formats, and even on music styles themselves: labels such as Cherry Red and Riot City moved production towards multiple track twelve-inch discs, while others adopted some production styles from the mainstream and began creating extended remixes of standard seven-inch single tracks specifically for a club market. Meanwhile seven-inch single sales suffered a widespread decline across all music genres, at least until the growth of the indie/DIY scene of the late 1980s, itself a successor to the punk DIY sub-genre.

Technological changes also had a major impact on the market for recorded music during the early 1980s. Improvements to the cassette tape format, which had been around since the mid 1970s, together with the launch of the Sony Walkman personal cassette player in 1979, led to a shift away from vinyl in the early 1980s, with cassette sales accounting for more than 50% of the album market by 1986. However, the success of the format was to be short lived. The Dutch Philips and Japanese Sony Corporations had been developing digital recording and playback technology since around 1980, and the compact disc was launched in Japan in October 1982 and in Europe in March 1983 as a new, superior quality, pre-recorded music format which was set to dominate the market over the next twenty years. New technologies were also to have a dramatic effect on the graphic design and printing industries during the late 1980s: on January 24 1984, Apple Computer launched the Macintosh, a desktop computer which was to have an enormous impact on the graphic design profession over the following twenty years.

The various punk sub-genres had also become strongly fragmented by the period 1983–84, in many cases evolving away from 'punk' definitions altogether. New Punk record sales were diminishing, and both the Oi and Anarcho Punk sub-genres had gone underground in order to maintain a movement well outside the mainstream music industry. Hardcore punk was evolving and forming crossovers with Heavy Metal, both musically and graphically, and DIY records were becoming more diverse and removed from any obvious punk heritage, with a strong market for the growing 'Indie' scene which impacted heavily on the national charts in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Personal collection as taxonomic research might be a way to at least partly describe your approach to the project; how much of the collection did you own prior to the formal outset of the study? And how did you tackle the opposition between a need for critical detachment against your highly personal relationship to the subject matter?

Before the start of the research, I owned probably around 60% of the records in the study. I had been buying and collecting punk records since I was a teenager, so it presented a decent range of material to start with. However, it was important to my methodology that I try to be as inclusive as possible, to cover the broadest range of punk and punk-related releases across the period I was investigating.

This meant setting some kind of benchmark against which I could map my 'data'—the full sample of records under review. I used a number of secondary sources to build a listing of relevant records to include: The Complete Book of the British Charts and Barry Lazell's Indie Hits: The Complete UK Independent Charts 1980–1989 (1997) were useful guides to national and independent chart records. Other invaluable sources included George Gimarc's Punk Diary 1970–1979 (1994) and Post Punk Diary, 1980–1982 (1997) and Greg Shaw's contemporary listing New Wave On Record: England & Europe 1975–8 (1978). There are also a number of retrospective listings, such as those by Martin Strong (1999), Vernon Joynson (2001) and Henrik Bech Poulson (2005). In 2007 Mario Panciera published what I think is the definitive guide to UK punk single releases between 1976 and 1979, 45 Revolutions, though this goes further than my study could and is more clearly a collectors reference guide rather than a 'history'.

My own collection and experience was also, of course, relevant—I started by listing the 'big names' from the period such as the Sex Pistols, The Clash, The Jam, The Damned, The Stranglers, Buzzcocks, Siouxsie & The Banshees etc., then those who made the greatest impact on the Second and Third Waves, including Sham 69, The Rezillos, The Undertones, UK Subs, Stiff Little Fingers, Cockney Rejects, Vice Squad, The Exploited, Discharge and Crass, and the great 'unknowns' who were revered by critics and/or fans: Desperate Bicycles, The Lurkers, The Vibrators, Television Personalities, Subhumans, Anti Pasti. So, my starting point was to list and scan the complete range of seven-inch releases by each of these groups—which meant I had to source those records to fill any gaps in my collection as I went on. Similarly, as the secondary listing search coupled with my own trawl through my collection threw up new artists, groups and labels to include, then these names led to further avenues to explore. For instance, some groups disbanded and members moved on to form other punk-related or Post Punk groups, and some groups worked together to tour or release joint recordings, and each of these offered new selections of material.

I already owned records by many of the groups listed in my research, though personal taste coupled with the fact that I was not a wealthy teenager at the time meant that I had only ever bought a fraction of the totality of punk releases each month. I had acquired more over the years, but there were still obvious gaps—especially when it came to groups or sub-genres that I didn't particularly like at the time. Since many punk sub-genres existed in opposition, or at least competition, with each other, this isn't really surprising—like most record buyers, I was purchasing records as a fan, not as a curator of a punk museum.

This brings me to your second question—the need for critical detachment against my own personal attachment to the subject matter. Histories are always going to be subjective, though many historians would try to support their arguments and interpretations through the use of extensive research and supporting evidence. In my case, I have very strong personal preferences toward some of the records I have included in the study—that is almost a given with something as personal as a record collection and the investigation of a youth subculture in part experienced by the researcher. However, I was also forced to include popular releases by groups I had ignored or avoided at the time, for whatever reason (anything from reading a bad review to simply never seeing a copy for sale in local record shops), and this has led to something of a revised opinion on my part.

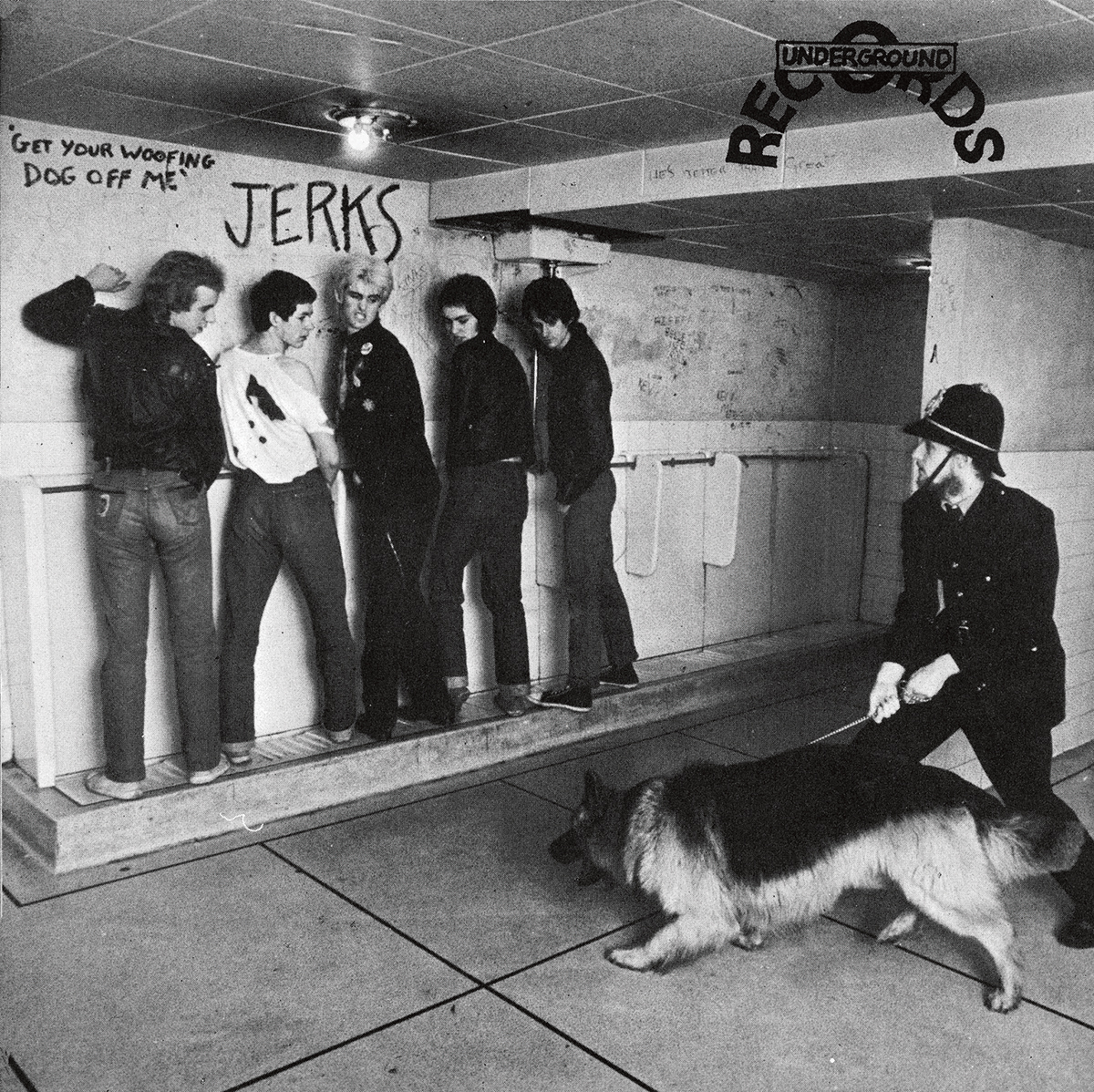

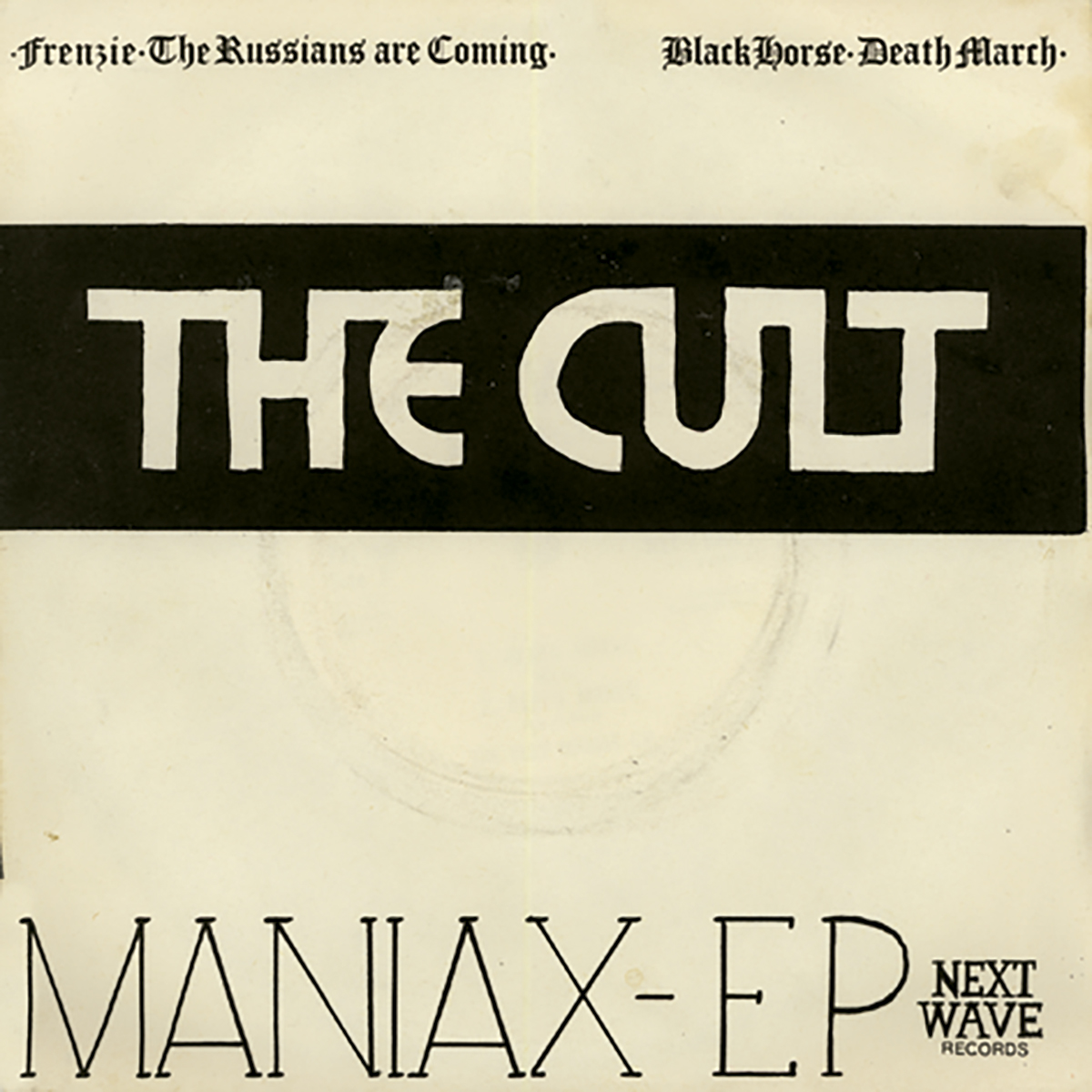

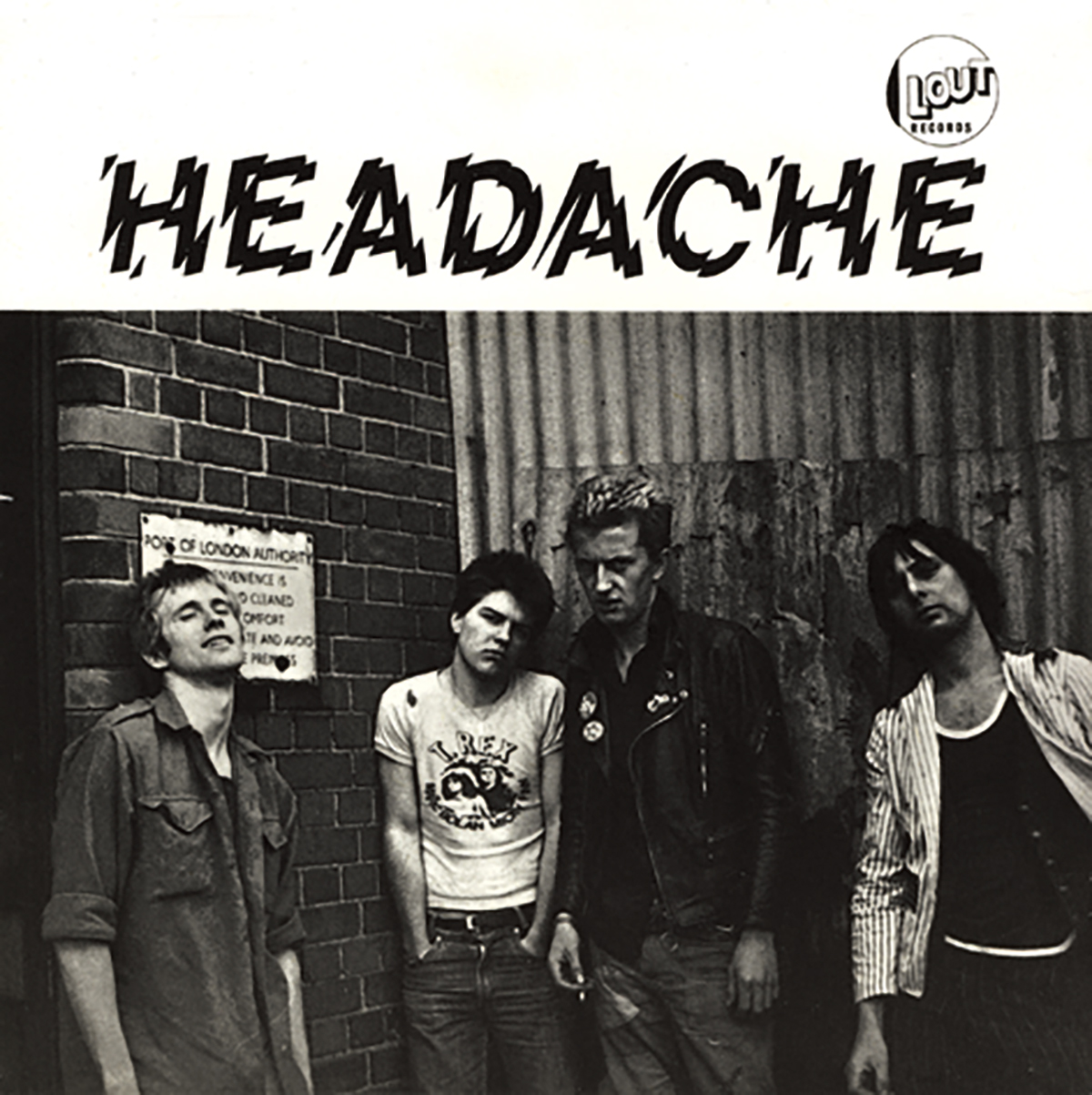

I have discovered some fantastic, long-lost (or never 'found' in the first place) classic singles by the likes of Blunt Instrument, Blitzkrieg Bop, Demob, The Partisans, Drongos For Europe, Joe Cool & The Killers, Headache, No Choice, The Pigs and a whole host of others, plus a few previously unknown (to me) new personal lifetime favourites by The Jerks (Get Your Woofing Dog Off Me), The Fruit Eating Bears (Chevy Heavy), The Wall (New Way) and the Cult Maniax (Black Horse and Lucy Looe). I have also discovered a personal fascination with punk parody records by the likes of The Monks, Norman & The Hooligans, and Neville Wanker & The Punters, and punk's internal critics such as the Television Person-alities, Snivelling Shits, The Ejected, and Chaotic Dischord—hence my renewed interest in punk humour. So I guess my opinions and tastes have changed along the way too—though 'objectivity' means I still had to include records and groups which I personally see no redeeming features in and probably never will be a great fan of: The Gonads, Cock Sparrer and the 4 Skins never appealed to me much, nor some of the more esoteric releases on Crass Records by the likes of Andy T and Annie Anxiety, but I can't deny the fact that they are all important to the substance of the research.

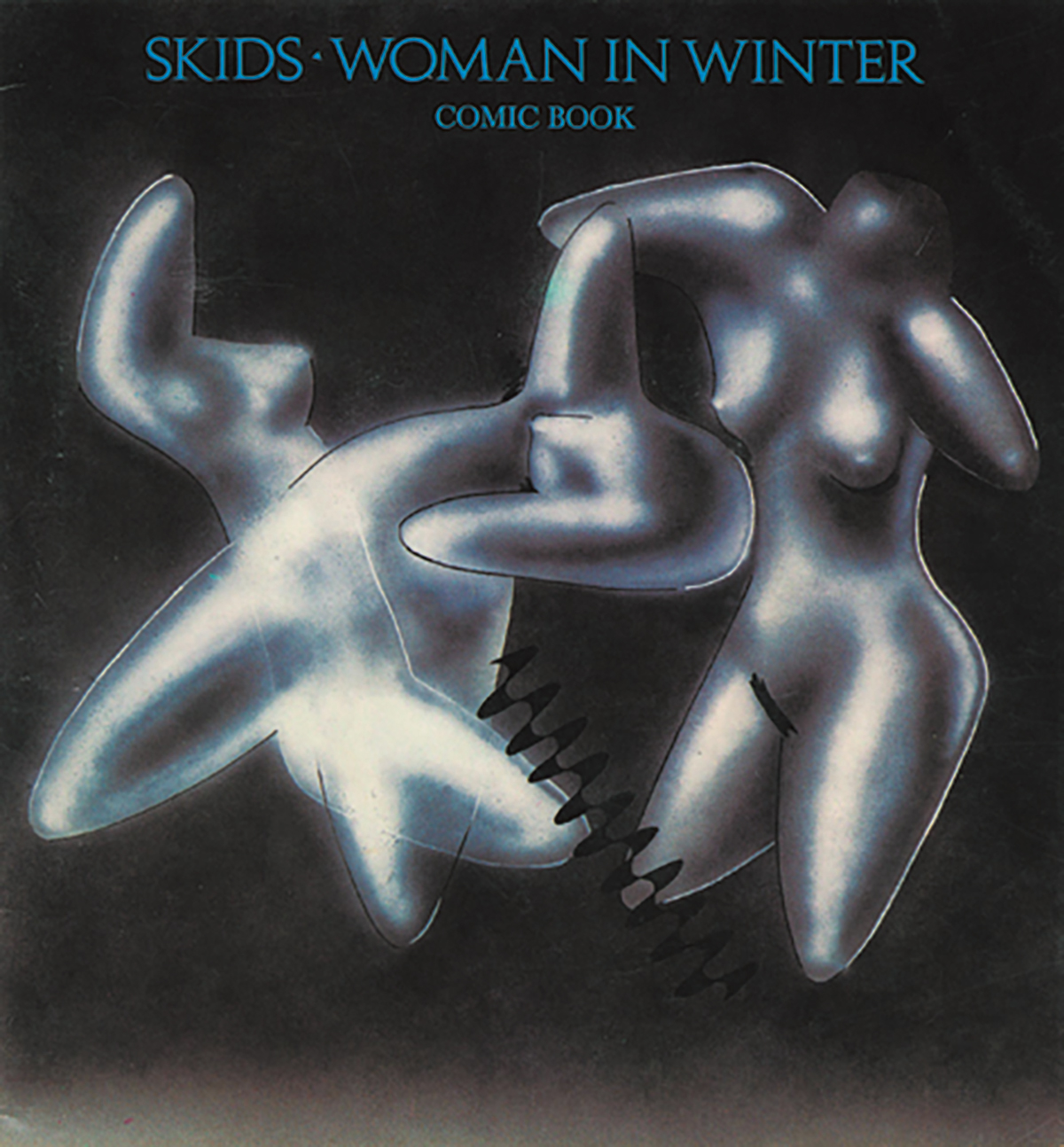

Finally Russ, what's your favourite and least favourite sleeve from the collection? I'm going to offer Here Today, Gone Tomorrow by The Strand and the very dubious Woman in Winter by The Skids (with apologies to Jill Mumford) as my respective choices.

Well, that's a hard question! I've just spent some time elaborating the methods by which I could put a sense of objectivity into the research, and now we're back to subjective judgements and personal favourites. As I said earlier, the subject is such a personal, emotive issue for most people who engage with it, it's very hard to get away from those individual responses in the first place.

Still, I'll give you a couple of answers. Firstly, as a fan it's impossible to completely remove myself from my own memories and experiences surrounding my own interaction with these records—a bit like that character in the Nick Hornby novel High Fidelity who arranges his records alphabetically, chronologically, and ultimately autobiographically. Therefore I'm going to nominate Grip/London Lady, the first single by The Stranglers, a record that triggered more than 30 years of fascination in punk for me in the first place. Not a great piece of design, though I think it does capture something of the glowering menace of the group at the time and is perfectly in keeping with the new 'punk threat'.

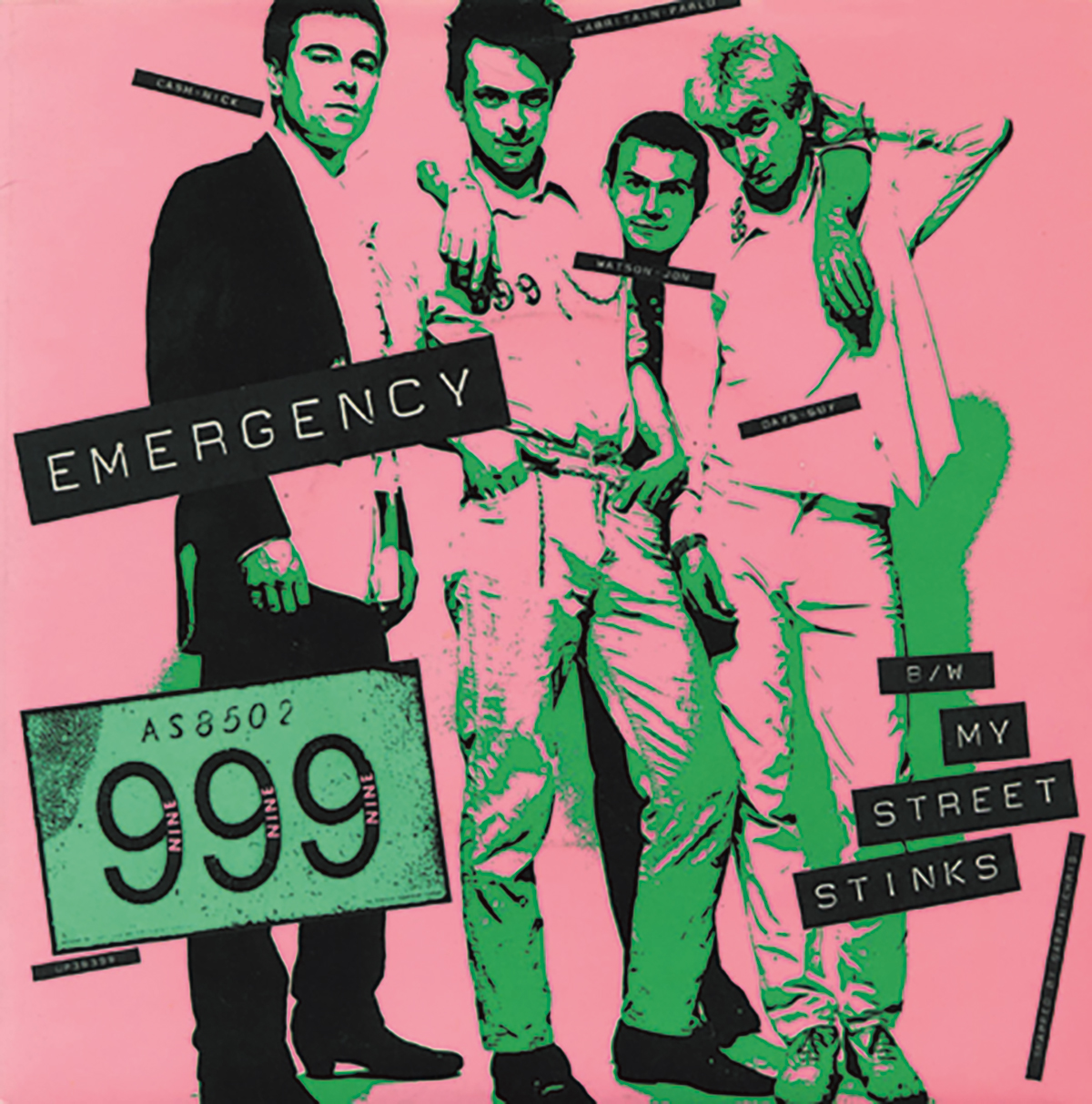

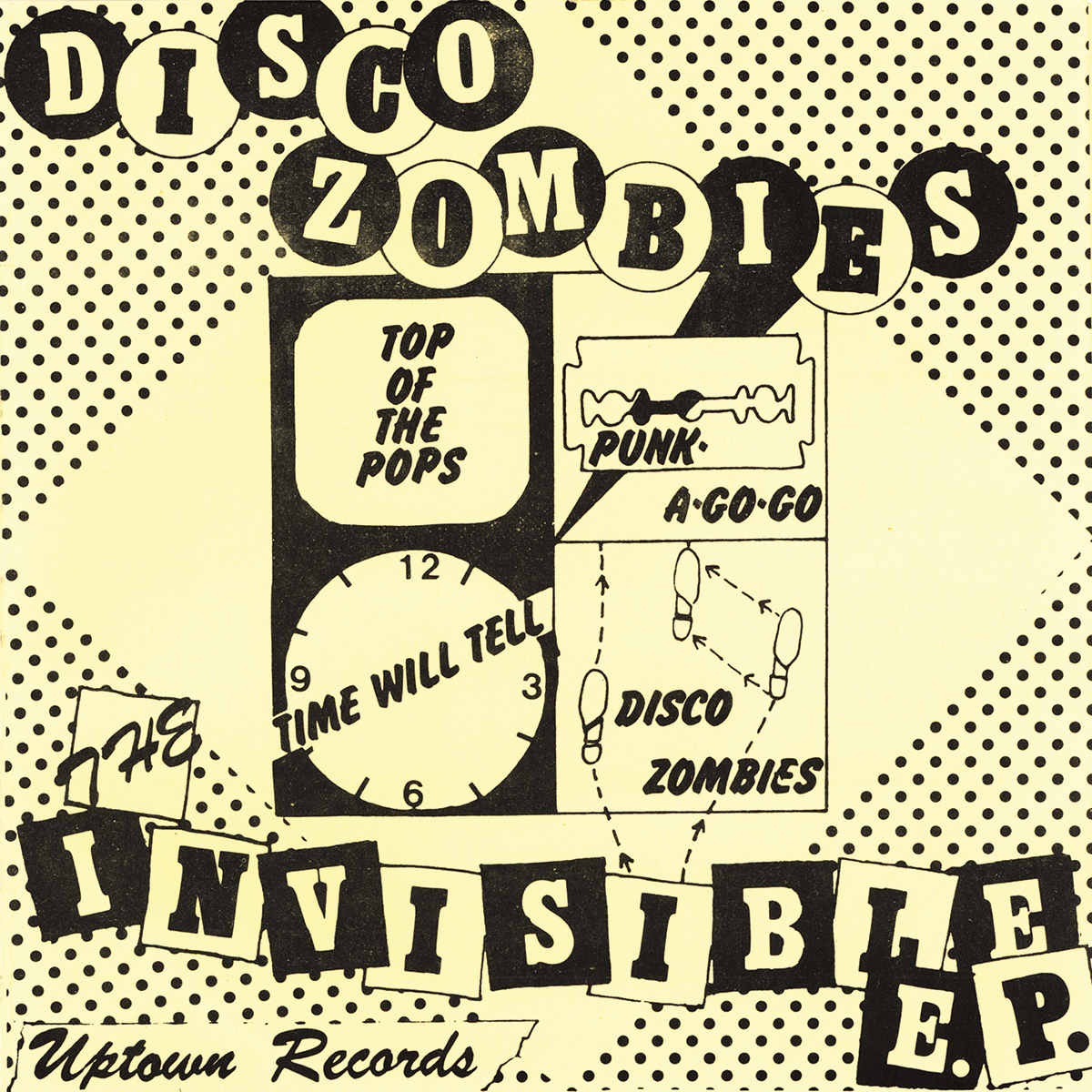

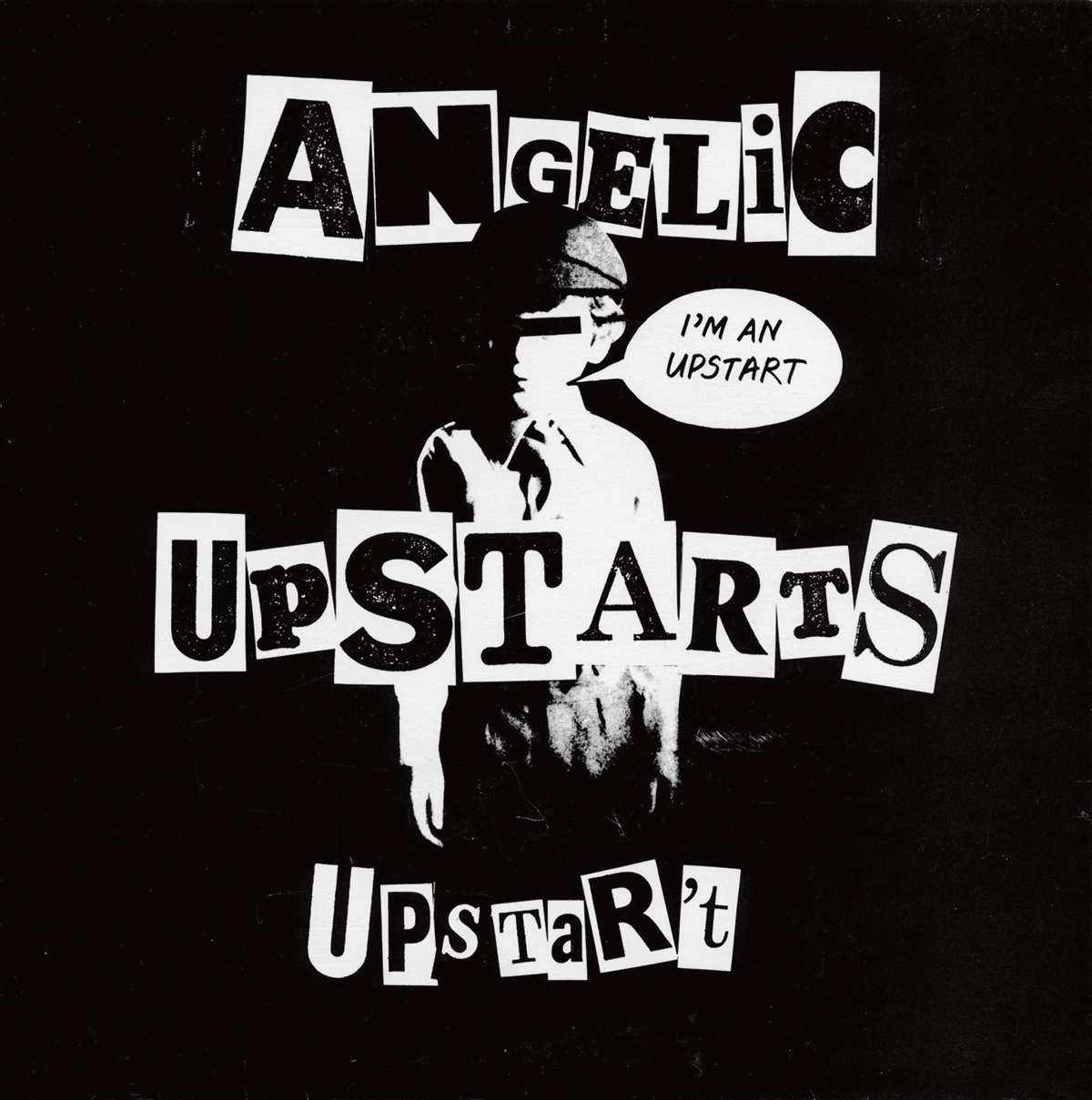

My second answer is really in retrospect, as part of my design analysis and history of the punk sub-genres, so I can try to be a little more objective. I have some great nominations for 'favourite', including UK Subs C.I.D., Blitzkrieg Bop Let's Go, 999 Emergency, Disco Zombies Invisible EP, The Vibrators Baby Baby, and Headache Can't Stand Still, but I am going to go for The Angelic Upstarts I'm An Upstart—a brilliant combination of several iconic punk visual devices all in one sleeve, including ransom note typography, a black strip across the main character's eyes, childlike rebellion against authority (and adults), and coarse halftone photographic reproduction. You just know what it's going to sound like as soon as you see it.

For least favourite, I would tend to agree with Jill Mumford's Woman in Winter sleeve—I'm not really sure what's going on there—or any of the later punk picture discs, a format completely unsuitable to the genre. A perfect example of record company management getting a little ahead of themselves in the marketing department!

Reference List

www.hitsvilleuk.com