The Aesthetics of Distribution, Part II – Luke Wood, Brian Butler

In September 2006 Brian Butler was appointed Director of Artspace, Auckland. Brian came to Auckland from Los Angeles where he had been running his own commercial art gallery, 1301PE, for the last 15 years. He has, however, recently returned to LA, and to 1301PE, having completed his three year term at Artspace. An interest in publishing was one of the cornerstones of Brian's tenure here, and something he plans to continue to work on through his association with Clouds, a new publishing venture for New Zealand art books.

This interview was conducted at DOC Bar on Karangahape Road, Auckland, on Wednesday 29th of October, 2008.

[00:10:10]

I was keen to know if this whole publishing thing was something you were doing before you came here? Or if it was a result of your coming here and seeing how badly we did it or something? Because I've heard you tell the story about Stella a couple of times,1 about having all the books in boxes in her bedroom.

Well, I think two things—I think one; I've always loved books and I've been interested in publishing and I've hung around people who're publishers—

Like who?

Well like JRP Ringier, like Revolver, and Walter Koenig.

So when had you met up with these people?

Walter Koenig I knew when I lived in Cologne in the early 90s, and he was making some books, but he was really selling books. And then looking at artists like Martin Kippenberger and Rosemarie Trockel—I liked the way they made editions, but also Martin made books. Sometimes they were small, sometimes they were bigger, sometimes they were self-funded, and he would find a way to distribute them; they'd get out, you'd find them in different places. But sometimes they were sitting in boxes—it was Fred The Frog Rings The Bell, I remember seeing boxes and boxes of at Max Hetzler's storage.

And then, what happened then—I opened the gallery and I remember meeting Nicolaus Schafhausen and he had Lucas and Sternberg, and then Christoph Keller started Revolver. And I thought that was quite interesting, how Revolver had started. It was basically a bunch of designers but then they realised quite quickly that they needed distribution, and they started very quickly also linking up to institutions—and then making that part of Revolver. And this is also the Clouds model. I think with Christoph though he kinda got burnt out on the day to day running—

And he sounds cynical about that institutional backing in the end as well?

Well that's a big conversation we can have. Because I think, in the end, I'm quite cynical about it as well.

Because he sort of cites that as the reason for getting out of Revolver.

Well I think that and I think if you can partner with JRP Ringier and you can do self-funding, you know, in other words you can sort of say: I'll get you, and you, and you, and you, and we'll all get the money together and we'll be much more cooperative about the project—then there's a real freedom to it.

One of the things I like about Clouds is that there's no Director's Forward. So it's not about me pitching or the Director pitching the project. I think we came to the agreement that you could have one that was perforated. But I thought if that's the case then why don't we just put it inside the shrink wrap? It's just something that sits on the back and it's like: “Hi!”

I thought it'd be really great to make fictional Director's Forwards. You know, really just stupid. Because I've never read a Director's Forward that has really enlightened me.

Yeah, so it doesn't need to be in the book.

Well it doesn't need to be in the book, but also, if it is in the book, then it's basically a hands on sort of thing. But I think the book should do it itself.

It's like what Fiona Jack and I were talking about; she's doing the next billboard and there's a really beautiful text that's been written by Layla Rudneva-Mackay—because of what the billboard is of—and she asked: “Where should I put it?” And I said: “Let's just put it on the website. We'll put it on the website underneath an image of the billboard. That's it. And then maybe we could put it in Volume 4.”

But this idea that we're gonna have to do `handouts' and, well, it's a billboard! You know? There's an idea that you have to `textify' everything—everything has to have an equal or similar amount of verbiage around the image...

Published by Artspace and Clouds

2008

Edited by Brian Butler, sub-edited by Gwyn Porter

Designed by Warren Olds

[00:15:40]

So I think there were those people, and then I was asked by Edgar Arceneaux to make a book for him. It was all the buildings on 107th St or something like that. It's a take, or a riff on Ed Ruscha's book, but it's the street that the Watts Tower is on. It's an accordian book—folds out—of course there's not half as many buildings or houses, it doesn't quite function right.

Was this at 1301?

Yeah. But it was a gun for hire job.

So did you actually design it?

[nods] Rudimentarily, I must say. I had no idea how I was designing it, I just remember laying out a whole bunch of photographs, and then the text I put in a certain place, and then we said ok that looks good. It was a book in two parts, one was image and the other was text, with two prominent African-American's writing about the project.

Then there was a book that was called Low Hotel that was for a show that I curated for Art & Public in Geneva. That was kind of an artist book, thin, it was supposed to be kind of brochure sized. And I think what I found was that all these books were sort of ok. And when I got here in 2003 they were kind of ok. But then I'd get home and they'd be scattered all over the place so you'd have to get one of those boxes that you put them all in, and then you never see them again.

I was just going through my stuff and I found the first catalogue ever on Elizabeth Peyton. It was a little book, like that big [indicates size with hands]. It was called Hotel, and it was when she did her show of her first drawings at a hotel in New York. Gavin Brown set it up. It was an edition of fifty with little hand tipped-in images. But the point is that it was lost and forgotten about.

I mean in a way it's a crazy collector's thing, you know, its what makes my wife crazy—cause she's like: “You just collect everything!” We put everything away and some day we'll have this amazing archive. But this friend was sitting in LA and he said: “What's that?” “Oh yeah that! Oh look there's those Rosemarie Trockel glasses.” You know? Half this stuff I forget that I have. Because I just kinda put it in boxes, and then I put the box away. And so some part of me is thinking, in terms of books, well that just doesn't work when you're an institution like Artspace.

So when I became Director of Artspace people came to me and said: “Artspace's publishing sucks. Under Tobias Berger there was no publishing as there had been under Robert Leonard. And what the hell was that Francis Upritchard catalogue? It should have been more. It's a very small, very thin little thing—a little cute little artist book. And, you know, Francis is far more ambitious than that. And there would have been an ability to garnersome support.”

I was just talking to someone today about her other book, you know the Human Problems one. And we were talking about how those kind of books get made overseas. Most of the time. Actually we were talking about the new David Hatcher book—

Yeah. Which is a Revolver book.

Yeah and like Michael Stevenson's This is the Trekka too. So you know there's this feeling that these sorts of books are always made overseas. Because my interests are fairly selfish I suppose—as a designer I want good stuff to work on. Good content. But you know, in the early days anyway, it just felt like I was always doing pamphlets, or extended pamphlets. And I think it was Danae who'd told me that you'd started up here and that you had this idea about saving the money from all the pamphlets and doing one big book. I think she was talking about doing the same thing at The Physics Room, and so of course I was like, oh yeah.

But they never did it. After the conference with Christoph Keller she really argued hard for the small book. And Christoph was like: “Ah no, it has to be a little bit sexy and show a bit of muscle.”

I was just interested in, and I think it comes out pretty well in Volume 1, a seamless sort of push that was visible between the international and the national, that if you pay attention—I mean it's funny that the One Day Sculpture project that Rikrit Tiravanija is doing is subtitled 'Pay Attention'. And it's kind of, in a way, for me, what my epitaph should be. Because if you paid attention to Artspace in the last three years you would have seen that there was a series of—well that I never saw an exhibition that you could take it by itself. But it ran into the next, and it ran into the next, and it ran into the next.

So you think the Volume series should work the same way?

Yeah. And they do. But also, then you put artists that you couldn't show in them. So if I wanna call Peter Madden and say: “Peter I want you to make some page work”, then you put him in within the context of what's in the Volume.

You're doing that?

We're getting there. I'm trying to figure out where Peter would go—which book.

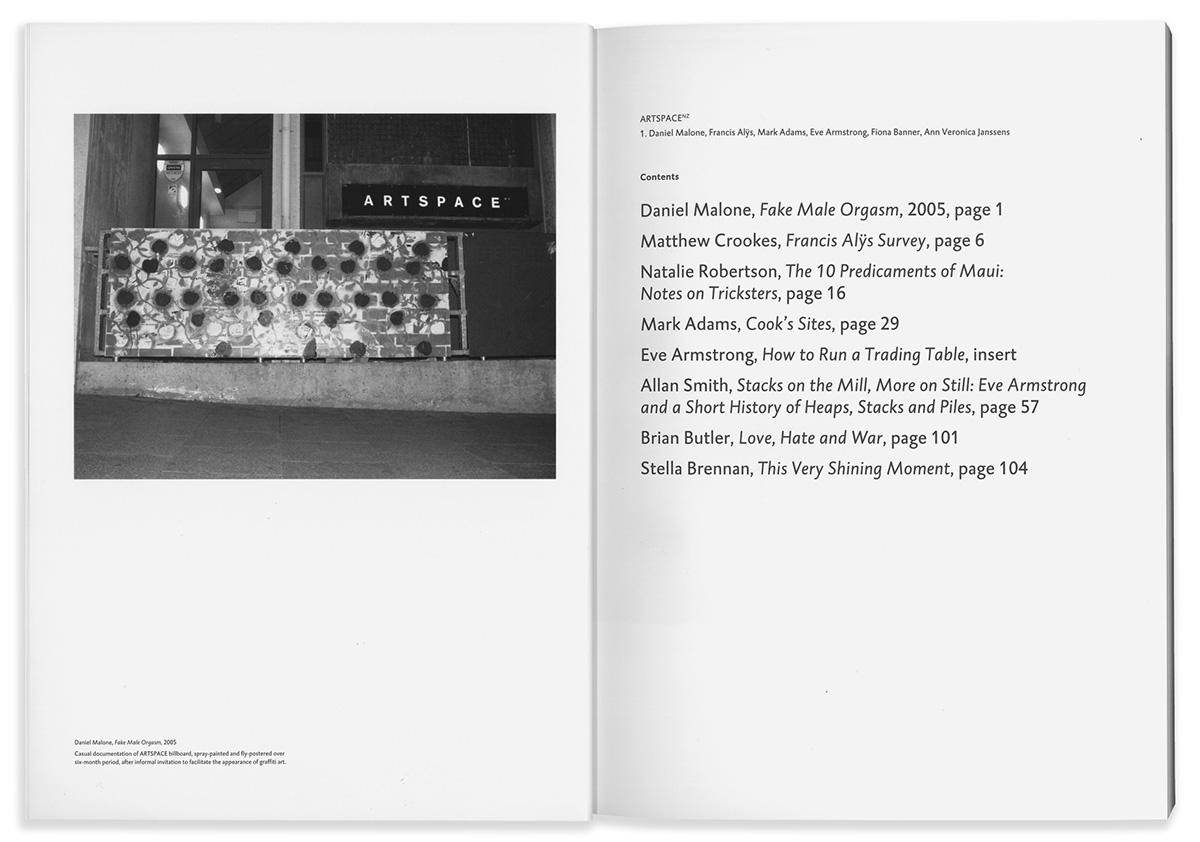

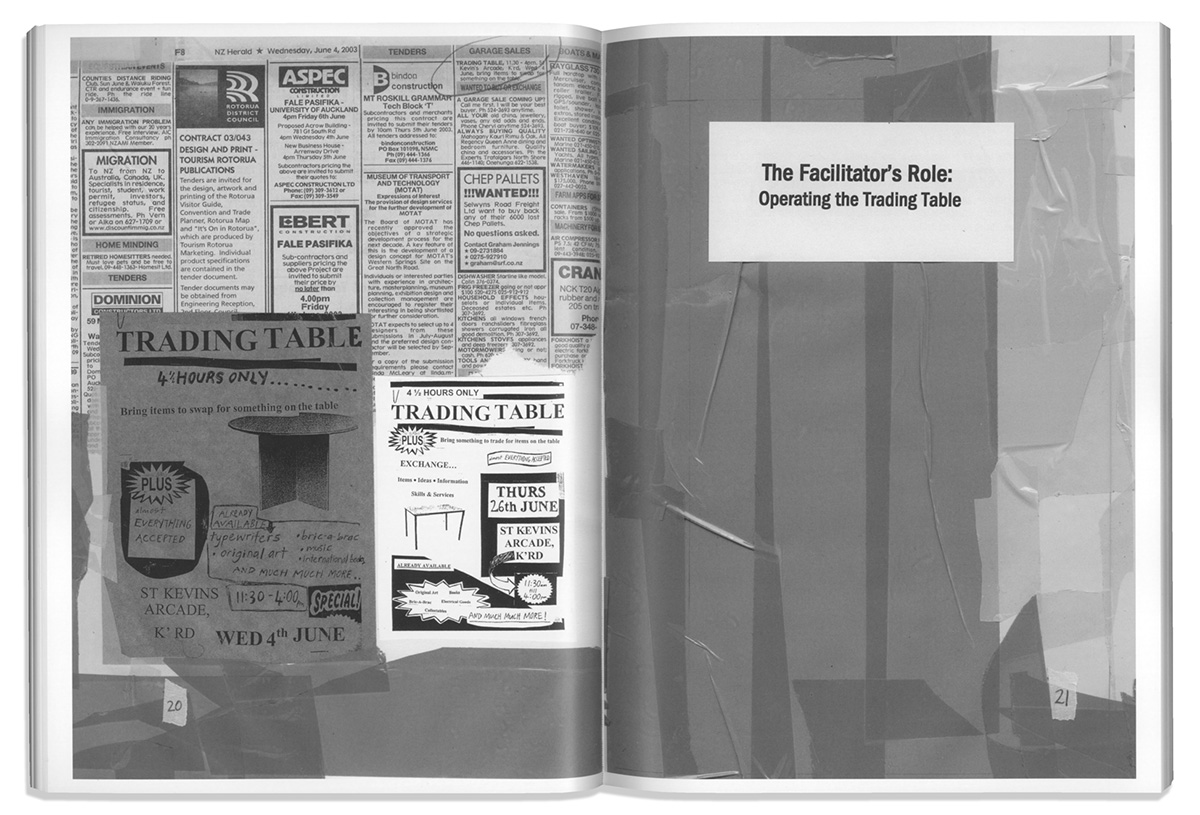

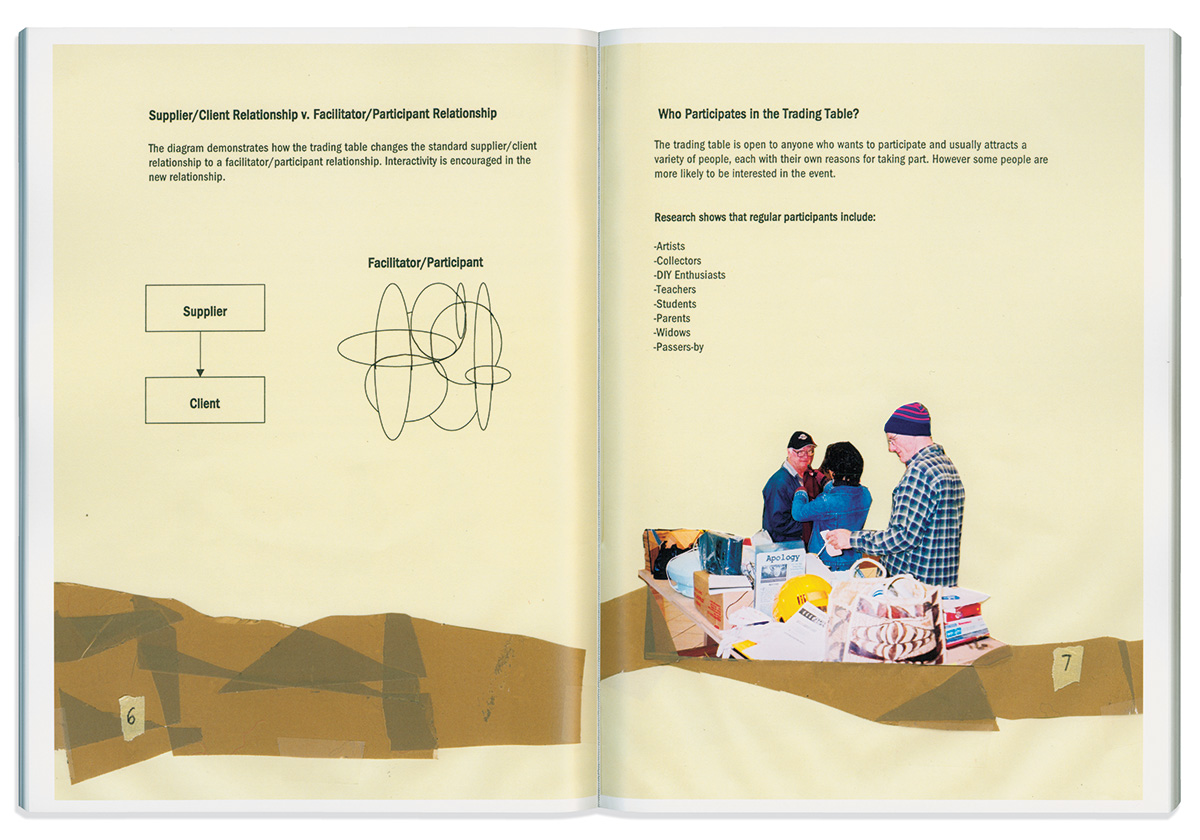

But it's the same thing. It's like if you look at the first one there's Daniel Malone, the tagging of the front of Artspace, and so it sort of locates the space. And then there's Mark Adams' photo essay, there's the reprinting of Eve Armstrong's How to Run a Trading Table. But Mark Adams, if you noticed, there's no New Zealand in those photographs. It's only non-New Zealand sites of Cook. So it's like Whitby, Middlesborough, Greenwich, Tahiti, Hawaii, Botany Bay. I think that's everything? I think Tahiti's in twice. That's because all of his colour photos are non-New Zealand sites—

I just realised I overcharged you by two bucks. These are four dollars at happy hour.

Wow.

You could buy a beer with that at Artspace.2

Um—so yeah, it goes like that, and that's one of the things I like about what the Barrs' observed, is they said Francis Alÿs sits very naturally and nice beside Eve Armstrong. You know it just becomes these sort of things.

So in a way it's a magazine, or there's a journal sort of way of thinking about it. But in another way we're also trying to manipulate the buyer, to go: “Oh I want Francis Alÿs” or: “Oh I want Eve Armstrong”, depending on where you are in the world. If the book is distributed in the UK then people will go; “Oh Fiona Banner.” Because it's about people being self-served. When you're in a book store, you're not altruistic—saying: “Gee that'd be really good for me as New Zealander, I should buy that book.” You go in, and go: “Oh I really love Eve Armstrong, I have to have...”—you know, I'm just thinking about record collecting. Right? I had to have every single thing that 4AD ever made. You know?

Yeah, and I guess on some level I get these books because Warren's designed them.

Yeah. At some point in time what I'm hoping is that Clouds will be like Revolver, in a way. Where Warren can't do everything, and won't want to do everything, and so he'll bring in people. Be it you, or Layla, or Sarah, or like various people who are coming up, or even going off-shore. All these things are possible. Or that Artspace could happily say: “Look we want to do something with Arch”, and that doesn't mean that it won't get Clouds distribution. So if Inhouse wanted to say: “Look we just want to be part of your lexicon, so we'll give you the design for free.”

When I first heard about Clouds I actually thought what it was going to be—because people have always talked about this, and I've seen it for myself because I've worked in a museum—was these basements full of boxes of books from the last 25 years. And so I first thought Clouds was going to kind of get those, collect those together somewhere, and start sending them out.

I think that's phase two. I think phase one was to set up a parameter, and then go to, let's say, the Govett-Brewster and say: “Oh by the way, all those Pae White, Christopher Williams, Sam Durant books?” The funny and weird thing is that the Govett-Brewster are just a bunch of control freaks. I mean when I bought the Pae White book, because I worked with Pae in LA, I then said: “Hey we need some more” because we'd given them away or sold them or whatever. And they were so slow at doing the distribution. And when I was then down [in New Plymouth] in 2003 I said to Greg Burke: “Can you throw in a Christopher Williams book?” And he was like: “No!”

Do they still have Christopher Williams books?

I'm sure they do. And they probably have them stuffed away somewhere, and they don't know. And I never understood that, you know?

So, for me at least, Clouds should do this—I think one; that the business plan, the concept, grew faster because the need was greater than both Warren and Gwyn could imagine it. So the first thing that happened was that Gwyn got pregnant and then had Ness, and there was a very fast realisation that this little creature was taking an enormous amount of energy. So her editing, like on Meg Cranston, was there, but there was Sue Gardiner and other people doing the editing too. And Warren was, you know, cranking away with Studio Ahoy and with Clouds. My question always to Warren was: “So what's the difference between Clouds and Studio Ahoy? Is Studio Ahoy the design armature of Clouds, or is it by itself, separate?” I think this is a critical and healthy question in the future. And, as we speak, Clouds is beginning to solidify.

So I understand that Clouds sort of came out of Christoph coming here? But then I think Christoph has said something like—because Revolver was a design studio as well as a publisher—that the design studio was paying for the publishing, and the books were basically losing money.

So, I guess, is Clouds a good idea?

Yes. But my feeling was that there must be a way that you could, or we could—Artspace could—supply the content. And we would get the set up—start the distribution outside of New Zealand. And Warren would supply the design, and then we would pay for the printing.

So that was my thinking. That we could start there. Then they would have content, then they would have books, then what they could do with the books is they could then go to CNZ3 and say: “Look we've done all these books, we've got European and American distribution, now we wanna go to Frankfurt, we wanna go to New York, to all these places, and you can help us get to there. And that will allow us to hire someone full-time doing the distribution, in Australia, in New Zealand, you know that person.” Because ultimately, what we know Warren doesn't want to become is Christoph. You know he doesn't want to become the guy who's running around doing the distribution and all that sort of stuff, and not getting to design. You know that ultimately led to Christoph's burn-out and fleeing to a farm in the south of Germany.

That doesn't sound too bad actually!

So I guess, one: I was always interested in distribution; two: I thought that New Zealand had the capacity to make some really interesting publications. I've said this again and again, that I think the designers who are here are really interesting. I also think we can do whatever we want to do. We can put a book in whatever order we want to put it in. When you're up in the northern hemisphere there is a belief in a certain order. Some of the arguments we had about some of the books in terms of ordering!

I mean why can't you shove everything—all the imprint information, all the acknowledgements and everything—on the one page, and put it right at the very beginning?

I listened to you on Kim Hill's show last weekend, and it sounded like you think of LA as a bit like New Zealand in a way—

It is.

You compared LA to New York, and it's like New Zealand's on the same sort of periphery—of where it's, you know, supposed to be happening.

And I think the danger happens in the same time and place, which is as soon as New Zealand gets big on itself and it starts navel staring in a really boring way. Because it's like: “Aren't we good, we're world class now.” And this is exactly what happens to LA. You know, LA goes: “We're world class, look we're in the New York Times.” And then it kind of breaks apart, and then interesting things happen again. Whereas Australia in a way, it's playing a different game I think. It's got such a big continent behind it that it can say, well we're far away and we are important.

It sounded like you were saying that there's more freedom because you weren't considered to be in the centre of anything important or something.

Sure. Absolutely. It's only when people care about what you're doing that it gets shut down. Because people then have vested interests. They become either protectivist, or they see that there's money involved, and then more money comes in, and then they control you.

Just look at any art school. When it's really interesting is when nobody gives a crap about it. And the teachers are there and they're all working away, and then somebody says: “Hey let me get my friend in?” And then they get their friend in. And the next thing you know some-body else is in, and people are going: “Wow, what's going on out in Riverside, it's kind of interesting.” And then you realise it has this world class group of photographers sitting there working away. And all of a sudden somebody says: “It's important now”. And then it just goes like this: the weight of administration comes down on it, and then marketing, and it all begins to shut down from the weight.

And I think that's the good and the bad of New Zealand. There's so much freedom to do stuff here. I think the greatest problem New Zealand has is probably a perception that it's so far away. And I don't think that's a problem at all. I said to somebody on November eighth, I will say for the last time, it is the easiest flight in the world, between Auckland and Los Angeles. It's a ten hour flight. It's the greatest red-eye you'll ever take. It's a horrible flight from Los Angeles to New York. It's the same hour time difference when we're in our summer here and LA's in its winter. Three hours difference. Twenty-four hours difference in Hawaii. Which means zero time at all. You know, and you fly up to Los Angeles—ten hour flight—you leave here at seven-thirty at night, you get there at ten in the morning. Same day.

Yeah you don't really get jet-lagged on that flight to LA. It's quite natural.

The first time I ever went to the States I flew to LA and hired a car. And I was really worried how that was going to go. You know, that I'd be jet-lagged and tired and then trying to drive around in this strange city. But yeah it was strangely familiar or something. I thought maybe it was because we've seen so much of it in the movies.

I think it's a lot of different things, I think Auckland and Los Angeles are very similar in that they are dysfunctional cities. Like Brussels, like Milan. You know? Maybe Brussels and Milan have more of a centre? I say any city that comes in low on the ranking of Conde Nast is interesting. San Francisco comes in really high. Queenstown, Melbourne—

Queenstown?...

[00:42:35]

Auckland is not a friendly town. I know people who've come here and they sort of—I know the first time I came I sat down on Hobson St, I had no idea, somebody told me I should go over to Ponsonby, so I walked across Victoria Park in the middle of the night. And everybody was like: “Oh my god, that's crazy”.

I just wandered around by myself, and I thought; well this is a fucked up town, I guess it's really great. And yeah, they are cities of secrets—they don't reveal themselves in the first and they don't pretty themselves up to be nice. I'm really hard on San Francisco, even though I lived there. I lived in Berkeley, and I've always said if I was gonna live in the Bay area I'd live in Berkeley again, over San Francisco, because it's just a much more interesting city. To me, San Francisco is too organised, everything has its precinct. You know, it's all organised—there's where the artists are gonna be, and there's the rich people, and there's the Italians, and there's the gay district, and there's the business area, you know.

Hells Angels.

Hells Angels? Somewhere. But it's all so nice and neatly orchestrated. And the tourist comes and goes: “What little bit do I want?” And then you go to that bit, and “there's Haight Ashbury.”

In LA—where? You know. There are little townships in a way. And it's the same thing in Auckland. You can drive out to Ellerslie in Auckland and the next thing you know there's the Mexican Specialty place, there's the fantastic boulangerie. Why is it sitting there?

They're both cities you have to drive in.

Well you have to figure out how to get around. I mean even Brussels you can kinda get to some interesting places, but—

But you need a car.

It's pretty good to have a car. But also, I just think it's the way that people think about stuff. You know? Maybe because it's dispersed, in Auckland people kind of hunker down. But also like you live what—twenty, thirty minutes out of town?

Yeah. More sometimes, depending on the traffic.

And you come in when you want to. And it just seems to me that there's a logical trans-Pacific relationship that can happen in a similar way. And I think LA's a big market. So I think that you could probably, if you were a nature baby, you could open up a shop there and you could do really well.

We don't sell The National Grid in LA.

Well see, there you go. We could find a couple of shops that would take them and see what happens.

To me that's part of my interest in going to Los Angeles, to say: ok so if this is the starting point, you know—I know some of LA. I mean the thing about LA is it's also a really vicious city. It seems really nice, and everyone's like: “Hey we should do lunch.”

Vicious how?

Well I believe with New York you know exactly what you're gonna get. I think people step in the sewer every day when they walk out the front door, even though it's been totally Disney-fied, from what it was in the seventies and eighties, and even the early nineties. And really, come on, no one who's a normal person can afford to live there. You know, and you're either so grandfathered into the process, or you're living in a hovel, or you're probably living out in the Bronx, or Brooklyn, or Queens. But I think that in Los Angeles everyone's nice on the outside, and then you know, knives are pulled. So I think there's an underbelly to Los Angeles.

Somebody once described to me coming out of the desert on New Years to go into Baghdad. He was a desert asphalt geologist, this German that was teaching at Berkeley, and he said it was so amazing looking at those city people, they were plump and ripe for the taking. And I think that there is some desert relationship in LA that still is on the periphery. I think for all the manicured lawns and gardens, there's this understanding that it can all dry up and go away. And in the same way, though there's a lot of friendly hospitality, there's also a ferocity to the city. That's maybe also an energy that comes out—it too is on moveable land. I mean these are all sort of thoughts that I think some people have talked about, but yeah. I don't know where that goes—but somewhere.

LA bands?

Some good LA bands. Some good New Zealand bands.

A lot of good music's come from the West Coast of America.

Well of course. But I also think the most important American art for the last forty years has come from the West Coast. I mean trend-setting, changing the world, has come from the West Coast. Or it was first shown there.

So; Baldessari, Bruce Naumann, Michael Asher, Turrell, Irwin, Ed Kienholz. You know you can kinda go through all those people from the sixties; Ed Ruscha. If you wanna go through all the car culture guys, you know, Craig Kaufman and stuff. Those Gambia Castle guys, they like Kenny Price, who's ceramic. You have Peter Voulkos who was in the Bay Area doing his whole riff on ceramics, which changed everything, and Ken Price owes a lot to him. And then you just kinda keep going, you've got The Woman's Building so there's a big feminist movement, and people like Judy Chicago. And then you get to Paul McCarthy, and Mike Kelley, and Charlie Ray—even though Charlie's originally from Chicago. None of these people were always originally from LA, but that's where they all came to. And then there is the next generation of Diana Thater, Pae White, Jorge Pardo, and they're coming from the schools.

When I was at design school in the early nineties there was this big West Coast thing happening. You know with Cal Arts and then Émigré magazine. Was that sort of on your radar at all?

Yeah, in terms of design I always sorta knew these people were working around and stuff. And there was a lot of crossover, and they knew various artists.

Because it polarised a lot of people. It was quite big for us—to get our heads around at the time. It was quite exciting then actually, but looking back now it seems it didn't really go anywhere.

Well I think it kind of functioned with a certain type of architecture that was also sort of coming along at that time which has morphed into certain things, and some things—we owe a lot of apologies! But I guess you still have the space to experiment. In New York you don't have the same sort of space...

Published by Venice Project and JRP Ringier

2007

Edited by Brian Butler, sub-edited by Gwyn Porter

Designed by Warren Olds.

[01:00:59]

[new beers are delivered] Cheers.

Cheers.

So yeah, where were we? Somewhere. I think the long and the short of it for me is that I like to see books moving around the world. I agree with Christoph. He has written one of the texts for the next Volume, a text called 'Books Make Friends'. And I like that you give books to people, and what they mean, and what they mean to you, and what somebody else may cull from them.

That's been the thing for us about The National Grid actually, and something we never thought about when we started, was that it's been a great way to meet people. In fact I can't think of a better way to meet a bunch of people than make a book. Maybe make a record? But same thing.

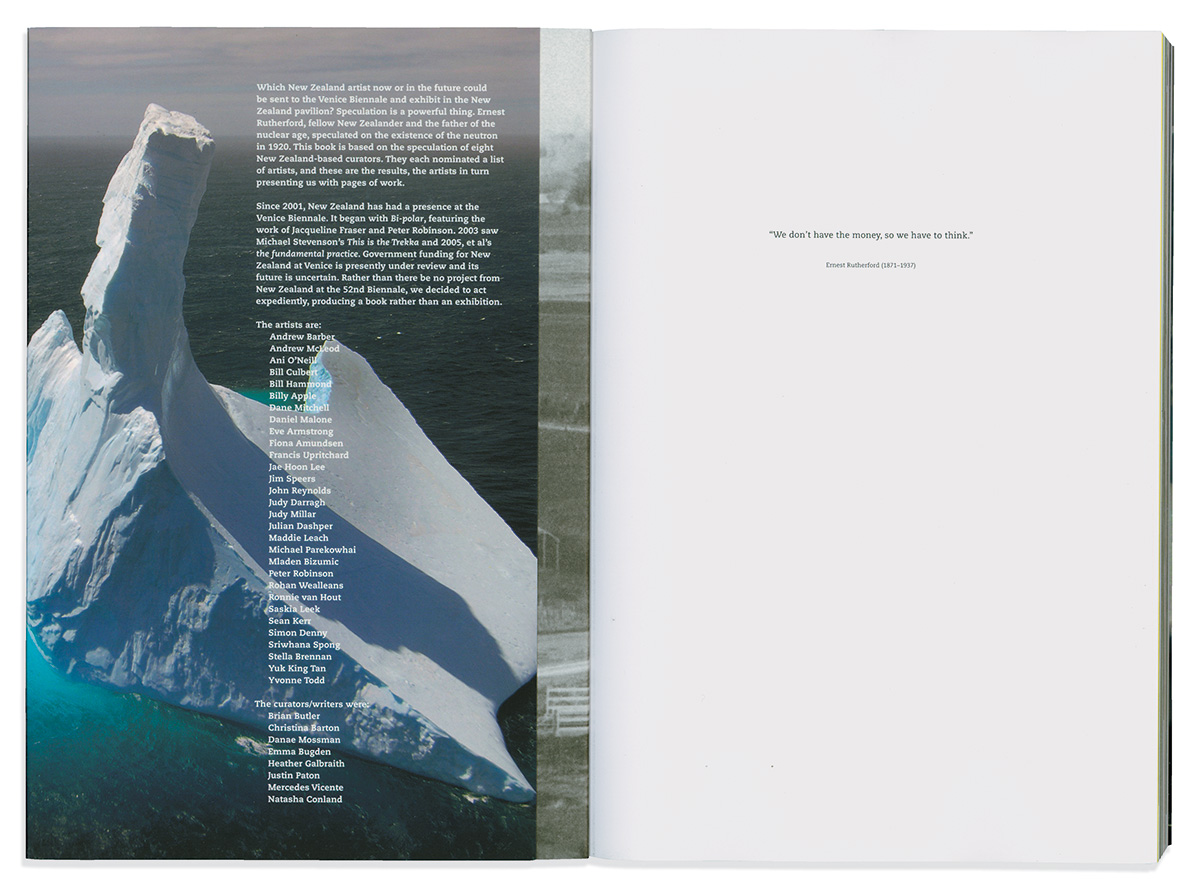

But you've hit the nail on the head, and this is what we said to CNZ when we did Speculation, and they said to me: “Oh we're going to do a brochure.” And I thought: why? If you're going to spend any money on this thing, throw a party and we'll give you a whole bunch of books. You know?

We don't want your money, we're an independently funded sort of thing. But we can get 42 Below to send their mixologist and a DJ over, you just rent the space and you throw a big party in Venice. And it can be for Speculation, for Brett and Rachael, and it can be for CNZ. And a whole bunch of people will flock in there, it'll be really great, and we can just hand the books out.

And did that happen?

No. Because that would take some sort of vision. And people would accuse them of being frivolous with their money. Instead, you know, they didn't do anything. Fascinating!

I'm really happy that Francis and Judy are there, but I think New Zealand has lost its great opportunity to really be—and this goes back to what I was saying on Kim Hill—nobody really thinks. We don't have to build a frigate to go do something. We should actually hold onto Lord Rutherford's comment “We don't have the money, so we have to think.” Now not having a lot of money may mean that you've got a hundred grand, and not two hundred grand. But it doesn't mean just because you don't have a lot of money, or because you do have more money, that you start thinking conventionally. What you should say is; we'd rather really think first, and then we'll find the money. And we might not come up with all the money so we can sort of move things around.

One of the things we talked about at the very beginning was the means of funding books, and one of the things that I despise and yet it's a part of the evils of an institution, is where you get most of your funding for publishing. And the Paul Winstanley book and the Meg Cranston book were perfect things. Peter Robinson's is taking more time because galleries here have less funds, so we have to find funds elsewhere and so it takes more time. And then—the thing I really hate, having come from a gallery position—then the institution pretends like they did it themselves!

So that is what I find so detestable about the whole proposition. And this is part of the reason I wanted to become the Director of a public institution, is that I've always said that if you're a space like Artspace you should function as a parish priest. In the way I see that most dealer galleries worth their salt function like parish priests—day-in and day-out they try and convert and proselytise. Most of them are completely committed to whatever they believe in. If you go talk to Ivan Anthony he's completely committed to his stable of artists. And Michael Lett is probably as well. And Starkwhite, Andrew Jensen, and Sue Crockford. And if you talk to Hamish McKay he certainly is. So for them, just because they are attaching money, as it were, or as I like to say, the parish priest who sticks the basket out every Sunday, and then half of it goes to Rome. And when he goes to Rome the Vatican pretends like: “We did it on our own.” Well, no. It doesn't quite work that way.

Published by Artspace and Clouds2008. Edited by Noel Daniel, sub-edited by Gwyn Porter, designed by Warren Olds. Curated by Brian Butler.

[Right] Paul Winstanley: Threshold

Published by Artspace and Clouds, 2008. Edited by Brian Butler, sub-edited by Gwyn Porter, designed by Warren Olds.

[01:07:42]

One thing I was keen to talk to you about was working with designers. Or maybe just working with Warren. Because it seems like, from the conversations we've had, that the sort of relationship you have with the designer is quite different to the sorts of relationships I've had with Directors when I've been doing books.

Yeah well for me, always, the book was artist-centric. So that's one part. I guess maybe with Volume it was a little bit different? Because basically I said: “Well let's sort of organise it this way”—so it had a chronology that was sort of set in, and then we figured out how to drop colour into it, with black and white text, and then so maybe that was more the two of us—but I always thought it was an exhibition in a book, or a series of exhibitions in a book.

I was interested in that, from what I know, you seemed to involve Warren in what traditionally is an editors role?

Well I think designers should.

Yeah but I think designers aspire to that. But it's still relatively uncommon that it happens.

I think the only thing that I have a beef with designers about is that they often times pick typefaces that are unreadable. So if you have a book that has text it should be really enjoyable to read. Other than that I think you should go do whatever you want to do in terms of the visual, you know. And if you wanna play with the text, like in Natalie Robertson's multi-voice piece—even though we couldn't use different colours—the idea was that you could read it and you could begin to decipher what was happening, that there were little things that were put in that were talking about Maui's voice as opposed to, or what could be considered a Maori voice, or the voice of a trickster compared to that which is supposedly an artist-scholar history.

Am I right thinking that you sit down, early on, and talk about the structure of the book?

Uh huh. But I also talk about it with writers. Like with Alan Smith, I sorta sat down and said: “Well what do you think?” And Alan kinda got a whole bunch of images together. And then we said: “Here, what do you think about that?” And I think there were some images that fell off, and some images that were costing money...

[01:16:40]

What do you think about speed? I remember when Robert Leonard was at Artspace he was sort of infamous for taking a really long time, and the publication might come out years after the exhibition had happened. He was fine with that though—I think he felt that the catalogue was something else, that it served another purpose anyway?

I totally agree. I think all catalogues should be written retrospectively, and I think that you should force the curator to sit in that show that they have curated and actually look at it, because then the exhibition will be the exhibition and the catalogue will actually carry forward, hopefully, the spirit of the exhibition. In other words, often times I find that the catalogues are more interesting than the exhibition. That's because the show was always made for the catalogue—it was always conceived as a catalogue. The curator doesn't ever touch the object, they never think about the object. And what they do think about is—and I talk to the curatorial interns about this all the time, particularly if they're quite academic and they've written theses and stuff, like a lot of them come into the programme and say: “So I wanna see my thesis as an exhibition.” And I ask why? What are you going to do? How is it going to push this way, or pull that way?

So I think the same thing's true going the other way. You do the exhibition first, you touch the objects, it all makes sense. I mean part of my idea about exhibitions, and the same thing about books, is to look. My job as a curator is to liberate, not to enslave. So if I put a work in, the idea is that whatever my original reason for putting it into a group show could have been, I should never tether it so much that that's the only way you can think about it. And so often the way curators enslave works is to serve their purpose. And so if I do a show about 'orange'—let's be really stupid—but if I do a show about orange, and each work is about orange, I can only look at that work now about orange. As opposed to the complexities of orange, and all the sort of stuff that can come bubbling up and go beyond orange. And so orange is only this big, and the bouquet is just gigantic.

And that's the same thing about books. It may start like that, but when you open it up it's like a pop-up book—all this stuff starts coming out. And then you're saying: “Wow, I read this thing about stacking, and then after that is this thing about lists. And that's kind of interesting what happens, those two things butting next to each other.” And one of the things, if I could've—if Alan would have had a chance to look at Fiona Banner's work in terms of stuff that existed outside of what was shown at Artspace, some of the work that's stacked—I love the idea that it would show up in both essays. Like the same work just gets reproduced again in a different context.

That's a bit like what you were saying before about the way you saw the shows at Artspace sort of bleeding into one another.

Yeah.

Do you think that always happens anyway and people just don't recognise it?

They don't pay attention. Because they're too focused on what the meaning of what this or that is...

[01:22:01]

I've said this, and I'll say it again, you know, without blowing your budget, if you follow the artist and you know they're an interesting artist, you'll find yourself in interesting places. And it's the same thing, if you're an interesting designer. I think designers are often like architects.

How exactly?

Well, you're building a house, a structure for something. And like there's a reason why Artspace is a beautiful space—that it wasn't totally ego driven when Nick Stevens did it. There was a generosity to the process in the way of thinking, in maybe making it artist-centric or making it space-centric, or whatever you want to say. On the other side of that, you know, it becomes all about the designer showing how absolutely cool they are. Then it doesn't matter if you have a book on Damien Hirst or a book on, I don't know, Nick Austin, it's gonna look the same. It's when the designer goes, ok let me get into the head of the artist, if that's the case. Or, how do I bring these things together and create a space that's a workable space, that these things can butt up and—at least for me, in terms of design, it begins to really work.

And that's when also, these moments where you say: “Wow you'd be the perfect designer to work with so-and-so.” It could be the worst thing ever because you might be too similar, but there might be these moments where you think, well that's really cool because I'm thinking this way, and I'm thinking that way, and these things can open up.

I've been thinking about working with people and wondering if it's an age thing. I mean when I came out of art school I felt like I knew exactly what I wanted to do, and I'd find it frustrating if the people I was working with didn't want it to go that way. I've been thinking about it because I see it in students, and it's made me realise I'm not like that anymore. Maybe it's because I don't have such a good idea about what I want to do anymore—whether that's good or bad I don't know.

I think that's right. I think at least for me the older I get as a curator, that's sorta what I just keep saying is you just have to, you shouldn't blindly trust anyone, but the idea of working with people and knowing what you're getting into, and giving it enough time to say no, as well as to say yes. I mean where you find yourself in problems is if you've got a deadline and you realise you can't say no. But my feeling often times about saying no is that no one will ever remember if you say no. Everyone will always remember if you say yes, and you sink...

[01:26:02]

Still, for me, it's like how do you figure out a way to say: Ok here's an interesting artist, let's figure out a way that, utilising the talent pool that's here, you can move those things in and move them through.

So this is, to go back to Clouds, what Warren and Gwyn want to do with it is obviously up to them and their business plan that they set forward, but I always saw one of the great things that Clouds could do is, if I'm sitting in Los Angeles and they have a channel of a whole bunch of stuff, and they're willing to print at not too high a cost, or to print wherever I want to print, that I could say: “Well, what I want is Luke to do the design and you guys to do the distribution and we'll pay for it.” And then it comes out of New Zealand, even though it's a book on Cerith Wyn Evans. And that in that budget we could somehow set up that there'd be a chance either for you to go to London or for him to come to New Zealand. And that physical shifting of presence would change the way that you think, or that he thinks, even though you may be doing something about work that's been made over the last three years.

One of the things I think happens to artists in the Northern Hemisphere, particularly if they're sitting where they're sitting, is that they think conventionally because that's where they're sitting. But if you move them offshore, off-base, you know. Christopher Wool is a perfect case. He totally controls his market in the US—he's produced more interesting things in Europe. There's a little Xerox series of prints that he's made, there's these books of photo-graphs that were done in Austria—you know these little things that creep up, that aren't what we know is the brand which is Chris Wool. So there's a playfulness that he can take part in in Europe which doesn't take place in the United States because the United States doesn't want to know that, it's too difficult. Only if you're an absolute aficionado of Chris Wool would you go, ok I need to have that. You know, it's like what happens to Martin Kippenberger who gives you a whole bouquet, and then people are going no, but I only want that. I want the self-portraits. I want the hotel drawings that are self-portraits. I want the drunken lamps. You know, they very clearly delineate and limit what Kippenberger is about, because it serves the marketplace much better than if people go, well we're not quite sure what it's about, it's awfully rambley. Even though it's not...

Footnotes

Story about Stella Brennan telling Brian about books she's published languishing in boxes in her bedroom. Brian refers to this anecdote in two separate radio interviews, initially with Lynn Freeman on 'The Arts On Sunday' (10 August 2008, 2:51pm, Radio New Zealand), and then again with Kim Hill on 'Playing favourites' (18 October 2008, 10:05am, Radio New Zealand). ↵

Referring to Superflex's Free Beer work at Artspace. ↵

Creative New Zealand (CNZ), an autonomous Crown Entity, is New Zealand's main arts funding body. ↵