Labels from the Post-Punk Periphery – Steve Kerr

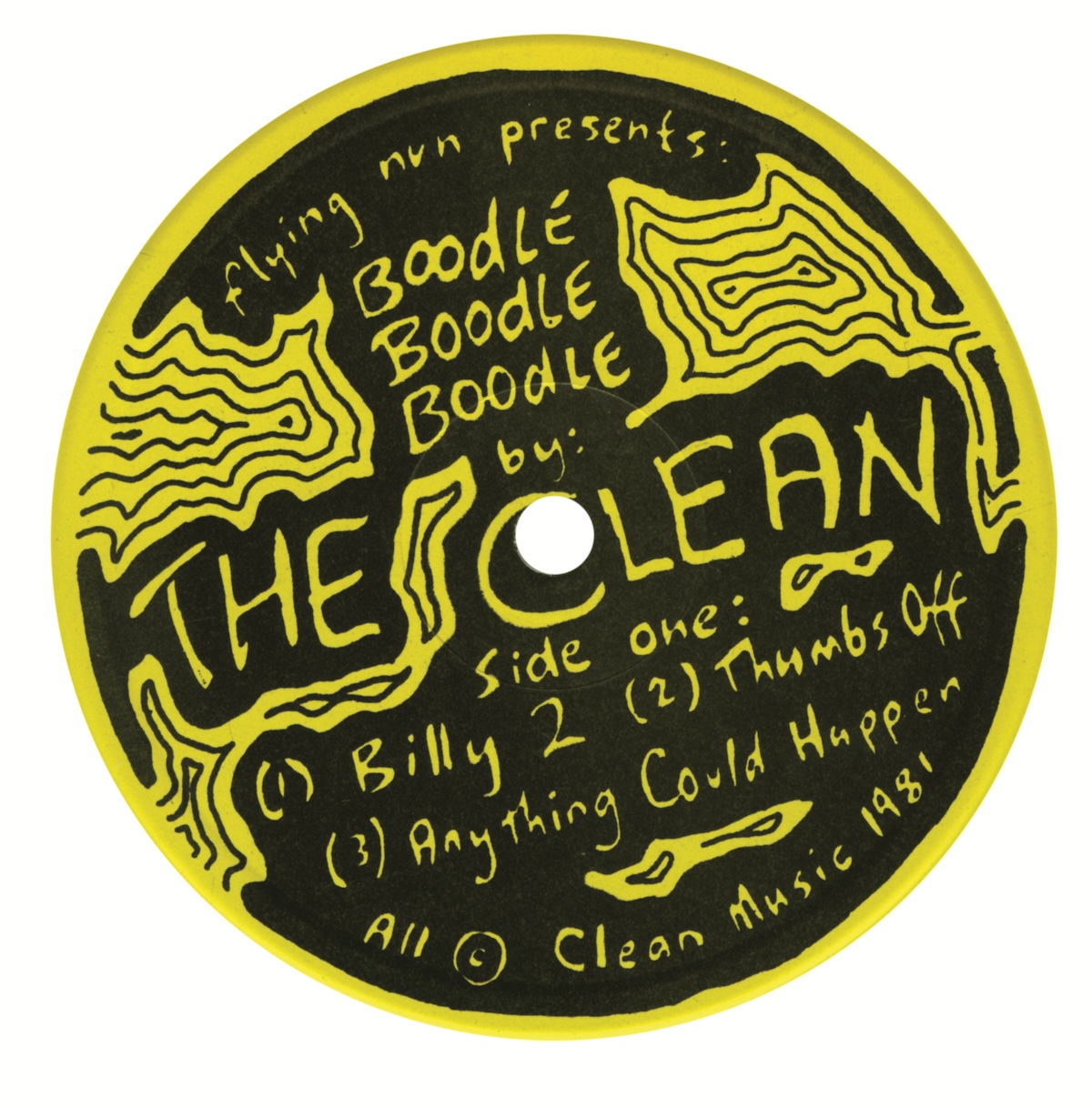

Boodle Boodle Boodle

EP, 1981 (FN003)

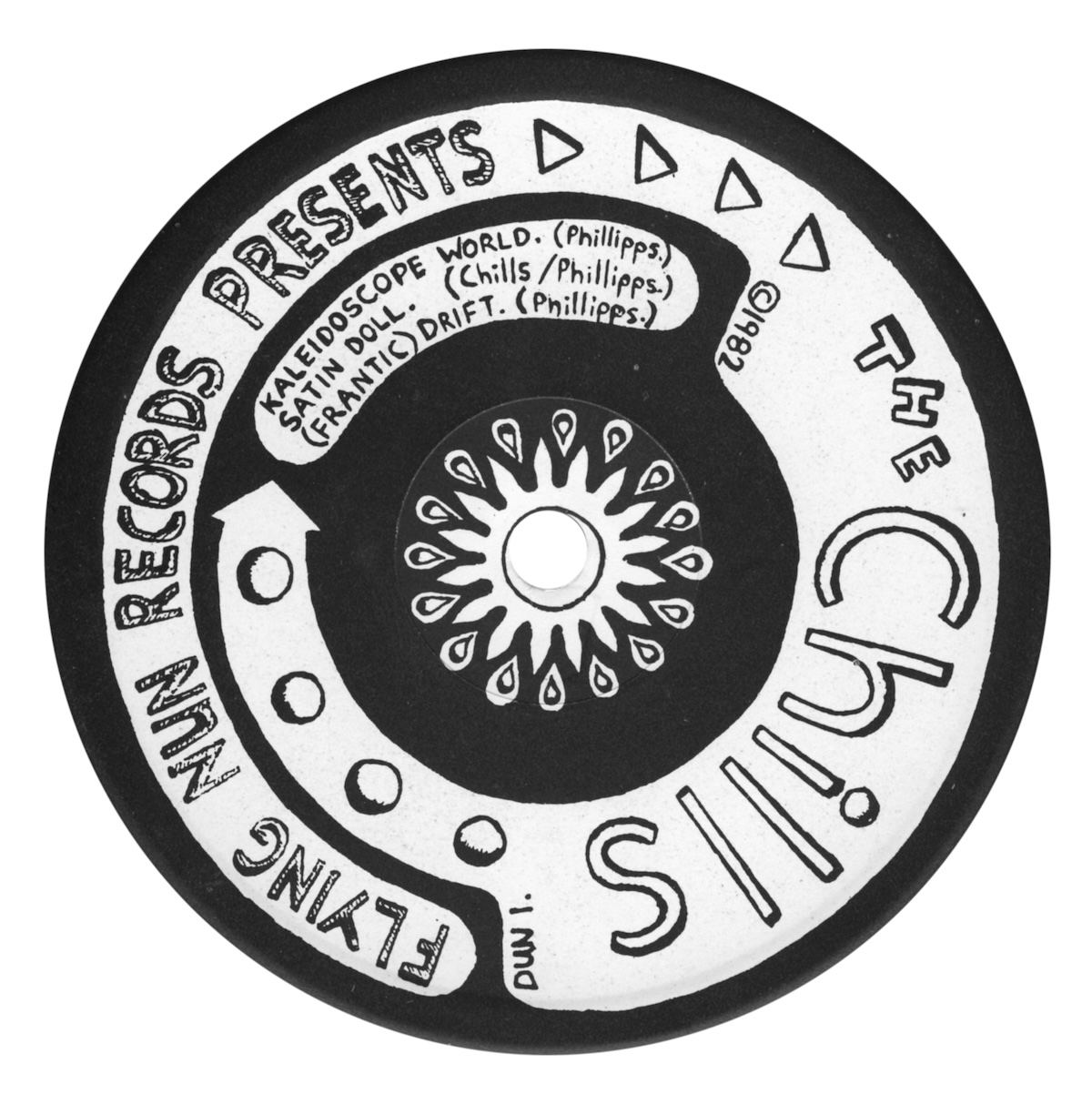

from Dunedin Double

EP, 1981 (DUN1/2)

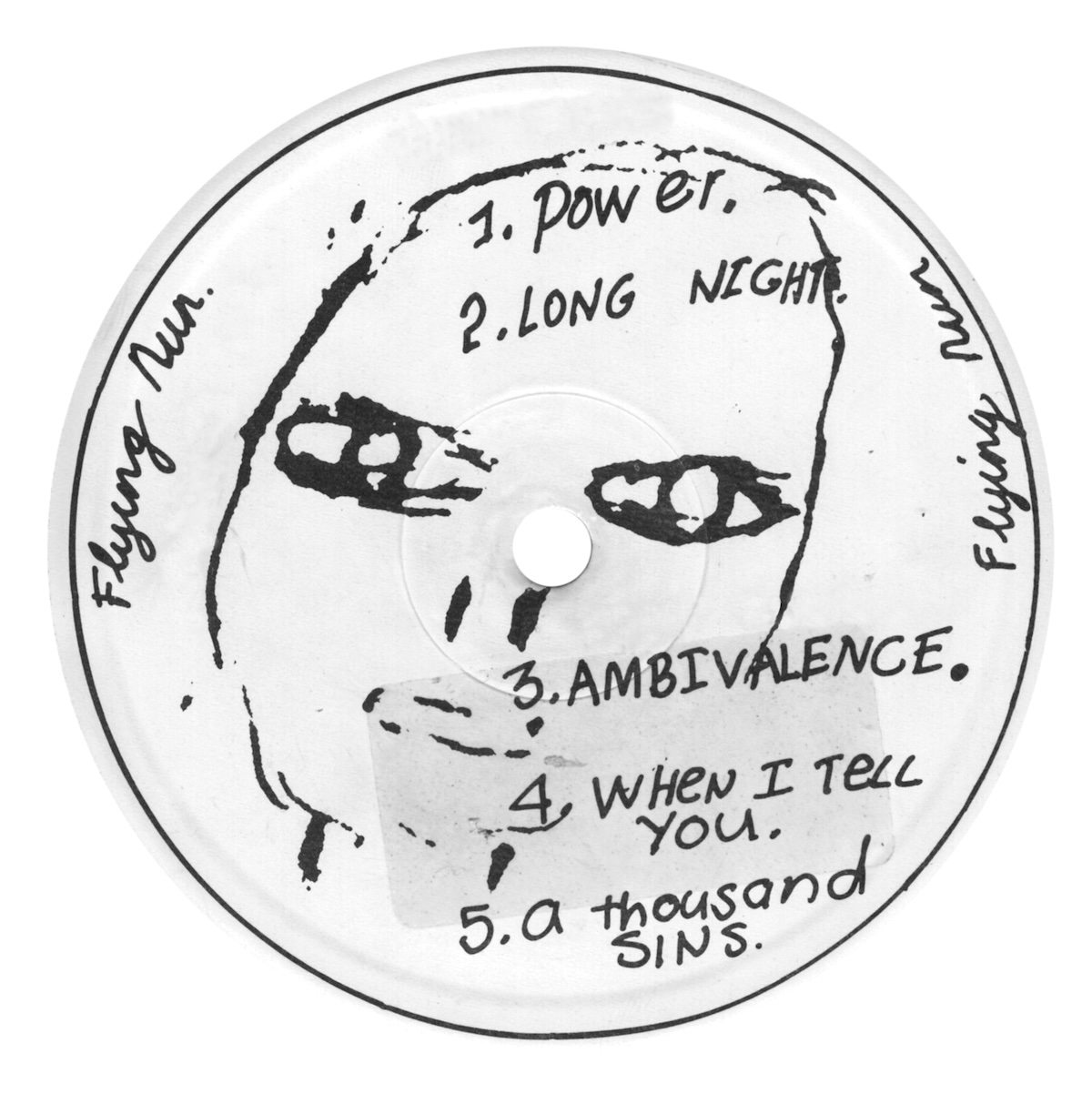

Louis Likes His Daily Dip

EP, 1982 (WEE001)

Louis Likes His Daily Dip

EP, 1982 (WEE001)

Pin Group Go To Town

EP, 1982 (FN 967)

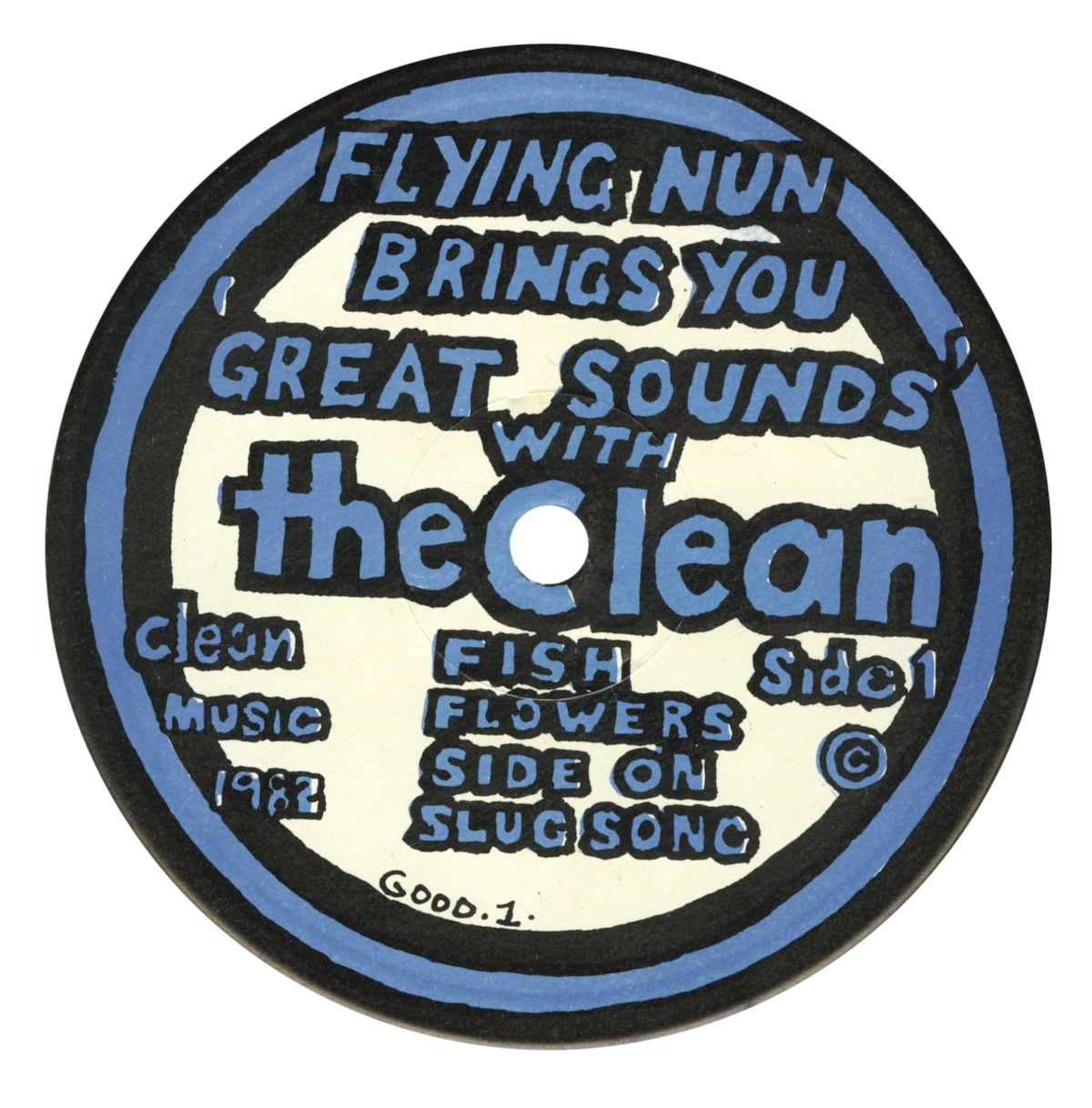

Great Sounds Great

EP, 1982 (GOOD 1)

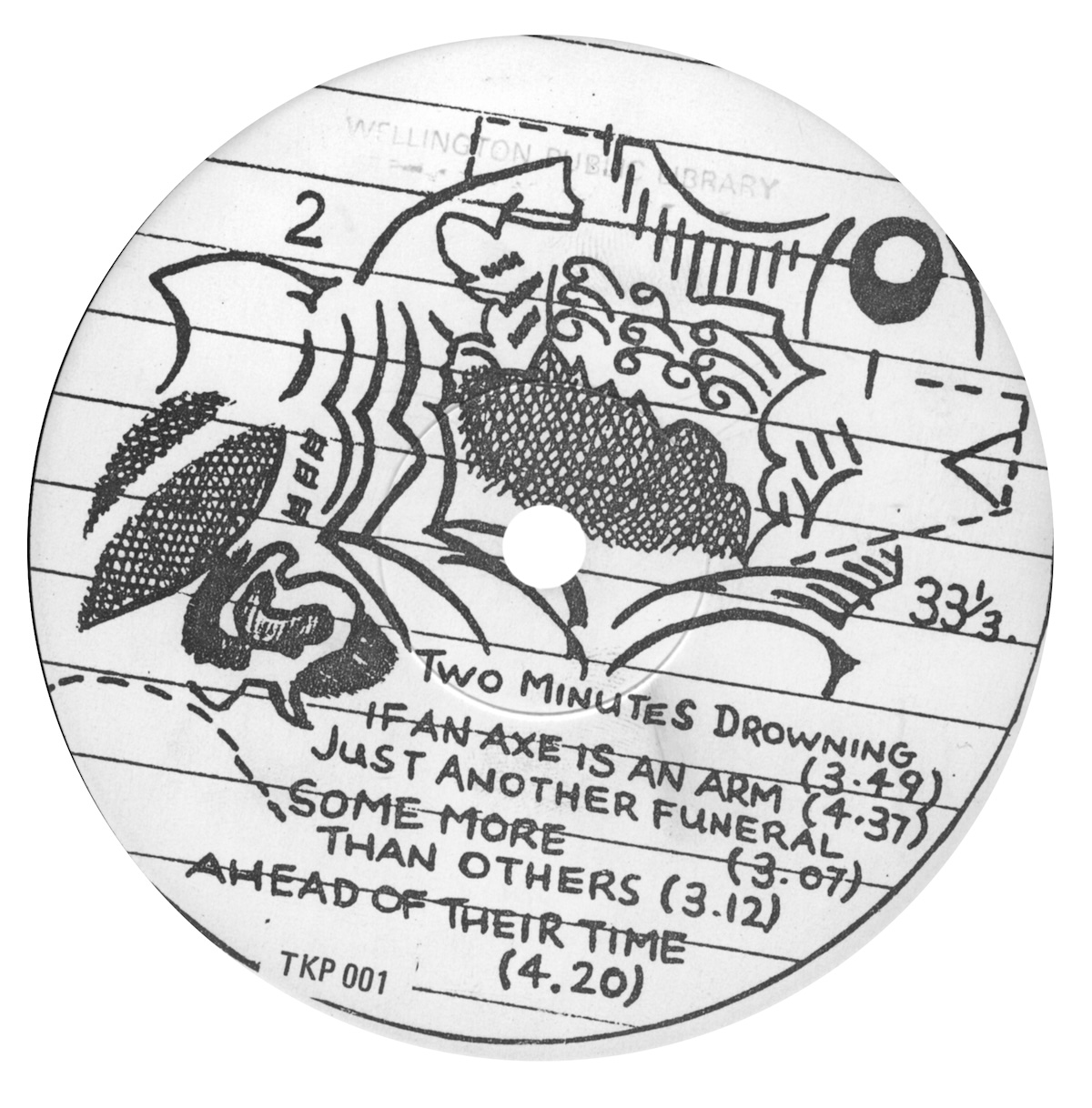

This Kind of Punishment

LP, 1983 (TKP001)

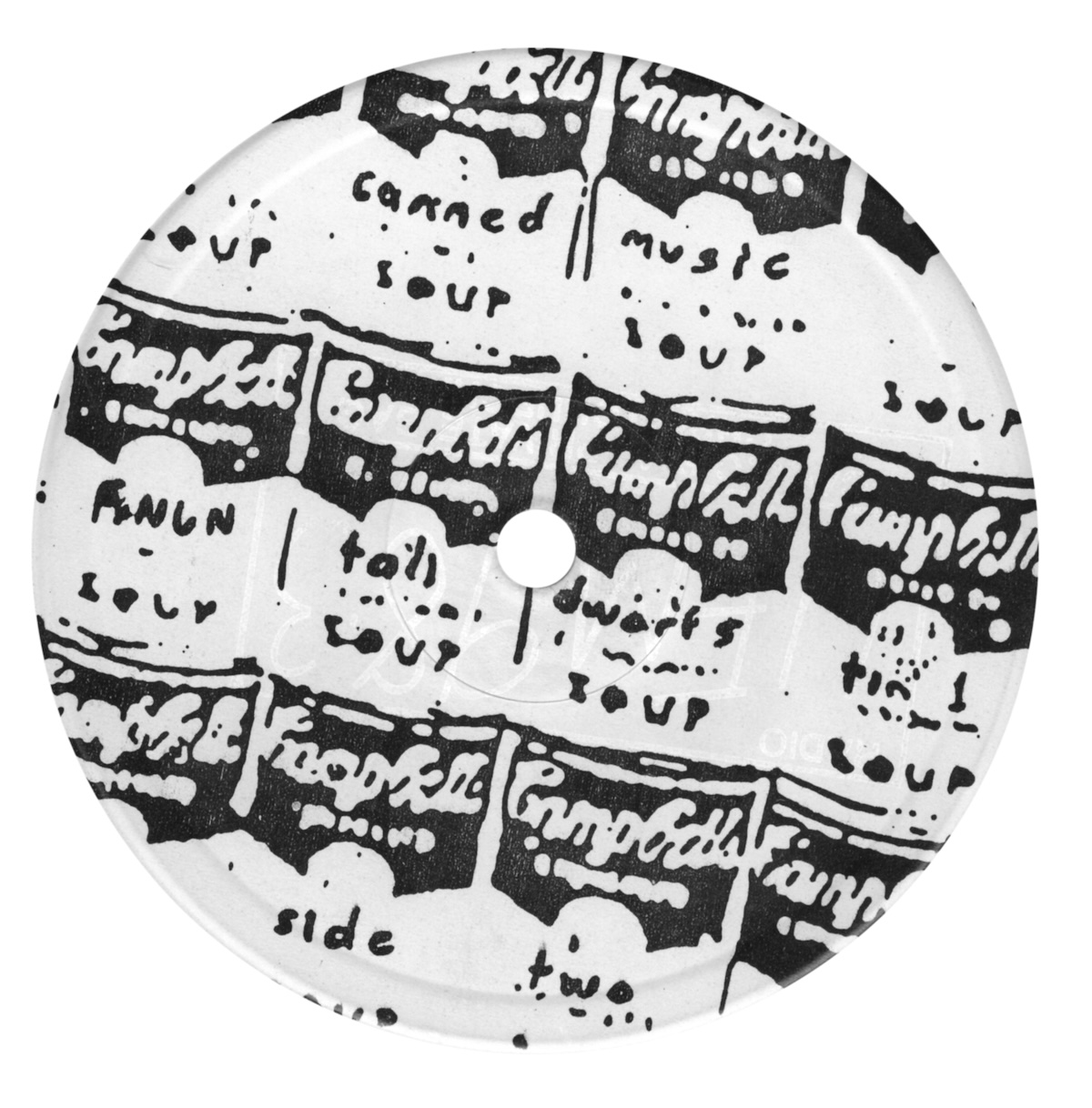

Canned Music

EP, 1983 (TIN1)

"Everywhere in light and calm the murmuring Shadow of departure; distance looks our way; And none knows where he will lie down at night." Charles Brasch, ‘The Islands’

"Everybody’s living overseas" Bird Nest Roys, ‘Ain’t Mutatin’

New Zealanders of a certain generation intuitively understand the importance of the independent record label Flying Nun to the cultural history of their country. They are familiar, perhaps over-familiar, with the image of black jersey clad bohos laying down their red wine and magic mushroom fuelled genius to a shitty TEAC 4-track, improbably changing the course of musical history from their remote corner of the world. Lauded by luminaries such as R.E.M. (back when they were cool), Pavement, and John Peel, it is surprising that little serious has been written about the significance of the label to New Zealand cultural life. This is not the place to start. Instead I intend simply to propose an approach which might be used to examine what the label means in, and says about, New Zealand.

I want to start by challenging the well-worn assumption that the ‘Flying Nun sound’ was truly unique, a Kiwi world-first to rank alongside the jet boat and the electric fence. The purpose of testing this idea is not to undermine the importance of the label, even less to devalue the talent of the artists who recorded for it. Rather, it is to provide a framework for searching for connections between local and international cultural production. By inquiring about where ‘our’ music comes from, about why audiences here respond to the music they do, and about how our music fits into its wider contexts, we might learn more about ourselves than if we simply continue patting ourselves on the back in a kind of lazy, indie-rock nationalism.

This text proposes first that the Flying Nun sound belongs in the international context of post-punk music, and secondly that New Zealand’s existing cultural preferences predisposed audiences here to being attracted to this genre. In other words, there are con- nections between New Zealand’s cultural identity on one hand, and the ideas in post-punk on the other, and these connections can help explain the success of Flying Nun. In the absence of actual research I am using Flying Nun record labels as a means of exploring these connections. We often forget that the term ‘record label’, used, as it most commonly is, to refer to a record company, is actually a metaphor. There should be something inherently instructive about a record label’s record labels. They are just the kind of forgotten graphic detail that might betray something essential about Flying Nun’s music and the people who made, released, and listen to it.

If we begin from the premise that the bands on Flying Nun, in its early heyday, were not creating music that was unique in the world, a couple of questions immediately present themselves. First, who else was making music in a similar vein, with a similar spirit or sound, drawing on similar influences, in the early 1980s? Secondly, what musical, social, or ideo- logical connections might exist between Flying Nun and these similar scenes? The answers to these questions should help us to place Flying Nun in its larger contexts: of New Zealand cultural life, and of popular music production in the Anglophone world.

Without wanting to slip into glib generalisations about the ‘Dunedin Sound’, it is useful to identify a few characteristic points about the artists who recorded for Flying Nun. Most famously, they shared a common passion for the ‘underground’ rock music of the 1960s: Bob Dylan, The Byrds, post-marijuana Beatles, Captain Beefhart, The Velvet Underground, and all the garage bands that they inspired. In retrospect much of the musical and thematic vocabulary of Flying Nun can be traced back to this music: spring reverb, twelve string guitars, and organs; the metronomic, driving beat of White Light/White Heat; psychedelic whimsy and paranoia; literary and artistic influences; bursts of noise, feedback, and tape hiss co-existing with classic songwriting sensibilities.

Next, the approaches taken by Flying Nun to music making and to business were complementary and interdependent. Most of the artists who recorded for the label in its early years had few commercial ambitions, and little affinity with contemporary popular musics, from hardcore punk to glossy romantic synth pop. The label’s releases were frequently experimental or cerebral, or at least harked back to the 1960s. Sloppy spontaneity, emotional and artistic authenticity, and originality of approach were preferred over the technical virtuosity and ruthless careerism seen as dominating pop music. That such artistic output could provide the basis for the survival, even success, of a small record company, is testament to the independent business approach of the label itself, and the strength of the local audience for this ‘alternative’ music. To a greater or lesser extent, the artists, audiences, and label all existed as separate from the ‘mainstream’ commercial music industry. So, while the label had a few notable chart successes (The Clean’s Boodle Boodle Boodle EP spent six months in the New Zealand charts, peaking at number five), its sales were for the most part confined to a niche market. Records were made very cheaply (The Clean’s debut 7" Tally Ho reputedly cost $50 to record), which allowed the label to pursue its own course: it was low budget, low tech, and proud of it. If part of the revolutionary raison d’être of independent record labels was to create a new economy where creativity and originality were privileged over corporate gloss, one manifestation of this was the absence of the kind of ‘brand identity’ you would expect in the corporate world. In its early years (before it moved to Auckland in 1988), Flying Nun survived with no consistent logo or house style. The name of the label was hand-written on records most of the time, apparently as an afterthought on the Double Happys label, and deliberately misspelt on EPs by The Stones (‘Flying None’) and Bored Games (‘A Flie In None Wreckid’). The Tall Dwarfs once represented the label’s name as a children’s pictogram. Adding to the chaos, artists would often invent self-referential sub-labels or catalogue numbers.

Looking internationally, there are strong parallels between Flying Nun and the UK post-punk scene, in particular the bands within that scene which identified strongly the DIY movement, and which felt a reverence for the 1960s underground. Bands like The Fall, Television Personalities, The Raincoats, Young Marble Giants, Joy Division, The Vaselines, and early Scritti Politti, certainly share their sound with early Flying Nun acts. In the US, jangly Anglophile ‘college radio’ bands like R.E.M., Let’s Active, and The Feelies had evolved along similar lines. Likewise in Australia, The Triffids and The Go-Betweens. However, in none of these countries did the local variant of the DIY post-punk sound become a pillar of national cultural identity, as it has done in New Zealand. Interestingly, international post- punk acts were, and continue to be, very well loved in New Zealand. The best example of this is Joy Division, whose albums and singles charted very highly here (two number ones and a number two single), but another is The Fall (who had three top forty singles and three top fifty albums in the early 1980s) who toured New Zealand in 1982. Given both the success of Flying Nun, and the popularity of international post-punk acts in New Zealand, we might expect some connections between post-punk the genre, and New Zealand as an audience. Three such points of contact immediately spring to mind: the do-it-yourself ethic, the experience of life at the periphery, and an underlying sense of unease.

DO-IT-YOURSELF

New Zealand, like other former colonial frontier societies, has a strongly established mythology about being a hands-on, practical nation. The title to the Bird Nest Roys EP which contains the line quoted at the beginning of this essay, Whack It All Down, sums up, in neat colloquial style, the ‘nothing flashy’ Kiwi approach. The do-it-yourself ethic was also central to the post-punk movement. In fact, it defined a strain of post-punk known simply as ‘DIY’. Acts like The Desperate Bicycles (on the ‘Smokescreen’ single) and Scritti Politti (on the ‘Skank Bloc Bologna’ single), published the costs of recording, producing and distributing their records as part of the cover artwork, following the movement’s imperative to ‘demystify’ the music industry. While these bands had an explicitly political agenda, one of the beauties of DIY was that it was equally well suited to serving financial/pragmatic, as philosophical/political, purposes. In the post-punk imagination, each reinforced the other. So, Flying Nun benefited from the happy convergence between post-punk’s celebration of DIY as an ethic and aesthetic in itself, and the practical means available to musicians in small South Island cities.

The same ideological fervour and financial limitations which lay behind the DIY approach to music production also spawned a deliberate design aesthetic, evidenced by Flying Nun record labels. The style is characterised by scribbly hand-drawn illustrations (a style described by Jon Bywater as ‘pencil-case casual’), fuzzy Xeroxing, screen printing, lyric sheet and zine inserts, rough cut’n’paste collage, and Lettraset or typewriter text. The majority of cover art was limited to cheap black and white, or one colour, printing. The messy, hand-made early covers of records by The Fall (for example the ‘Lie Dream of a Casino Soul’ single and the Hex Enduction Hour LP) perfectly reflect that band’s chaotic sound, and are iconic international examples of the style. As well as being the ideal approach for musicians on a low budget, the DIY approach allowed for a close connection between music and image production. Musician/artists like Chris Knox (Tall Dwarfs) and David Mitchell (Goblin Mix, Exploding Budgies, and later the 3Ds) were able to contribute the artwork, as well as the music, to their records. In other cases, visual artists from the same social milieu would contribute artwork to musician friends’ records (for example, artist Ronnie Van Hout contributed artwork to records by the Pin Group, Sneaky Feelings, and The Great Unwashed). Chris Knox and Alec Bathgate’s dogmatically low tech Tall Dwarfs project exemplified the potential for total synergy between the musical and graphic DIY approaches. Because both members had very strong visual skills, their covers are often more sophisticated than those of their contemporaries. The Campbell Soup pastiche of the Canned Music cover plays out the general Warhol/Velvet Underground obsession within Flying Nun, while the title of the EP references both krautrock pioneers Can and (ironically?) piped muzak. The back cover of the Louis Likes His Daily Dip EP recalls the Sgt Pepper’s collage.

ISOLATION: LIFE AT THE PERIPHERY

New Zealand is one of the most remote populated places on earth. This has long been an important theme in its arts and letters, and it is this fact of geography, as well as its size, that makes it particularly prone to self-consciousness and anxiety about its importance to everyone else out there, further north. The two quotes that open this essay address this sense of isolation. In much of his work, the poet Charles Brasch, founder of the journal Landfall and a pivotal figure in New Zealand literature, concerned himself with the relation between his native country and Europe, the ‘centre of civilisation’, as he and most of his generation saw it. The opening line to the Bird Nest Roys song expresses a similar idea, as, incidentally, does the title to John Dix’s Stranded in Paradise, which remains one of the few substantial books on New Zealand rock music.

Interestingly, more than most musical movements, post-punk celebrated the idea of life at the periphery. Not just life the musical/artistic periphery, or the periphery of the music industry, but also the geographic periphery. Simon Reynolds has discussed the importance of regional centres in the development of UK post-punk, characterising it as a moment when ‘the provinces rose up against the metropolitan monopoly over music culture.’ The most important acts in UK post-punk were not from London, but from centres like Manchester (Joy Division, The Fall), Liverpool (Echo and The Bunnymen), Leeds (Gang of Four, The Mekons, The Au Pairs), and Sheffield (Cabaret Voltaire, Human League), or from Scotland (The Associates) or Wales (Young Marble Giants).

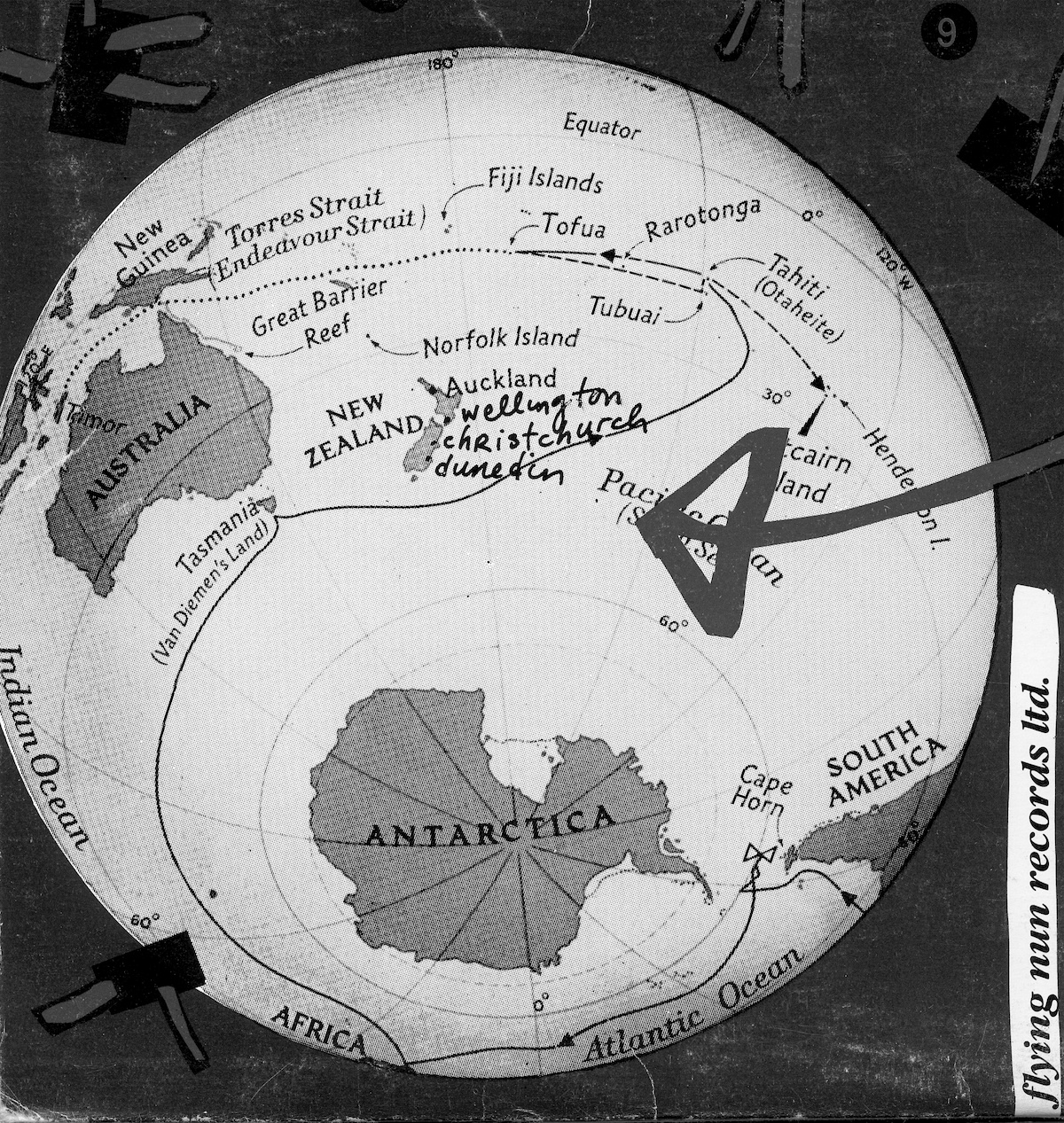

The back cover of the 1983 Flying Nun compilation Tuatara, features an unusual low-angle globe shot, showing New Zealand at the ass of the world. A crudely rendered arrow highlights this for anyone who might have missed it. Further playing out the centre- periphery opposition, the names of the other main cities have been added to a map which originally showed only the largest city, Auckland. Dunedin, the mythical home of Flying Nun, where the most important artists on the label worked, is located at the edge of the edge.

UNEASE

The music and look of bands like Joy Division and Cabaret Voltaire gave rise to the arguably unfair stereotype of post-punk being depressive and grim, or at least very solemn. The same traits have often been observed in New Zealand literature, and, for example, in Sam Neil’s documentary The Cinema of Unease, in New Zealand film.

While themes of oppressive or gothic darkness are present in Flying Nun (cover art illustrations by Chris Knox and David Mitchell show a clear fascination with the grotesque, and there is an industrial paranoia to the photomontage of obscured faces on the back cover of This Kind Of Punishment’s first album), it is the idea of unease which is most pertinent to Flying Nun, post-punk, and broader New Zealand identity. There is something intrinsically Kiwi, about the performances, especially the vocal performances, on Flying Nun records: they are often shaky, not tuneless, but awkward, modestly expressed. Vocals are half-hidden, low in the mix and swimming in reverb, giving an otherworldly sense of distance between the singer and the audience. The same sense of hesitance is present in the recordings of UK post-punk bands like The Television Personalities or Young Marble Giants. In part, this is simply a reflection of the anti-technique approach of musicians who celebrated shambolic amateurism. But beyond this, the diffident, even self-effacing, vocal style was ideally suited to lyrics in post-punk, which were often either intensely introspective, or deliberately oblique. Themes of inadequacy, self-doubt, and malaise seem to connect underground music and New Zealand cultural identity.

* * *

The rise of Flying Nun was a major cultural moment in New Zealand, one that deserves closer consideration than it has yet received. The approach proposed here positions Flying Nun bands less as isolated originators of something completely unique in popular music, more as avatars of a certain international sound: that of post-punk, and in particular the DIY school. It seems that several central tenets of post-punk are particularly compatible with New Zealand’s broader cultural identity. This could explain the success and enduring appeal of the label to New Zealand audiences, and the particularly strong appeal of inter- national post-punk acts here. In this sense, Flying Nun is a classic example of New Zealand artists and audiences, filtering the massive washes of British and American popular cultural product, and isolating certain themes and musics which are ‘real’ to them. Another example might be the strong growth in New Zealand hiphop since the late 1990s.

Too often in New Zealand we criticise as unoriginal or derivative any locally produced culture perceived as being excessively influenced by identifiable overseas sources. Just as frequently, we leap to make uncritical claims for our cultural production being unique in the world. Leaving such black and white assertions to one side and accepting that nothing is produced in a vacuum, we could be having a far more nuanced conversation about the way culture is received, interpreted, modified, and used here. Thinking carefully about the connections between local culture and international movements might offer a fruitful approach to understanding New Zealand’s pop cultural preferences and its wider society.

Another Disc Another Dollar

EP, 1983 (BUCK001)

Death and The Maiden

7", 1983 (FN014)

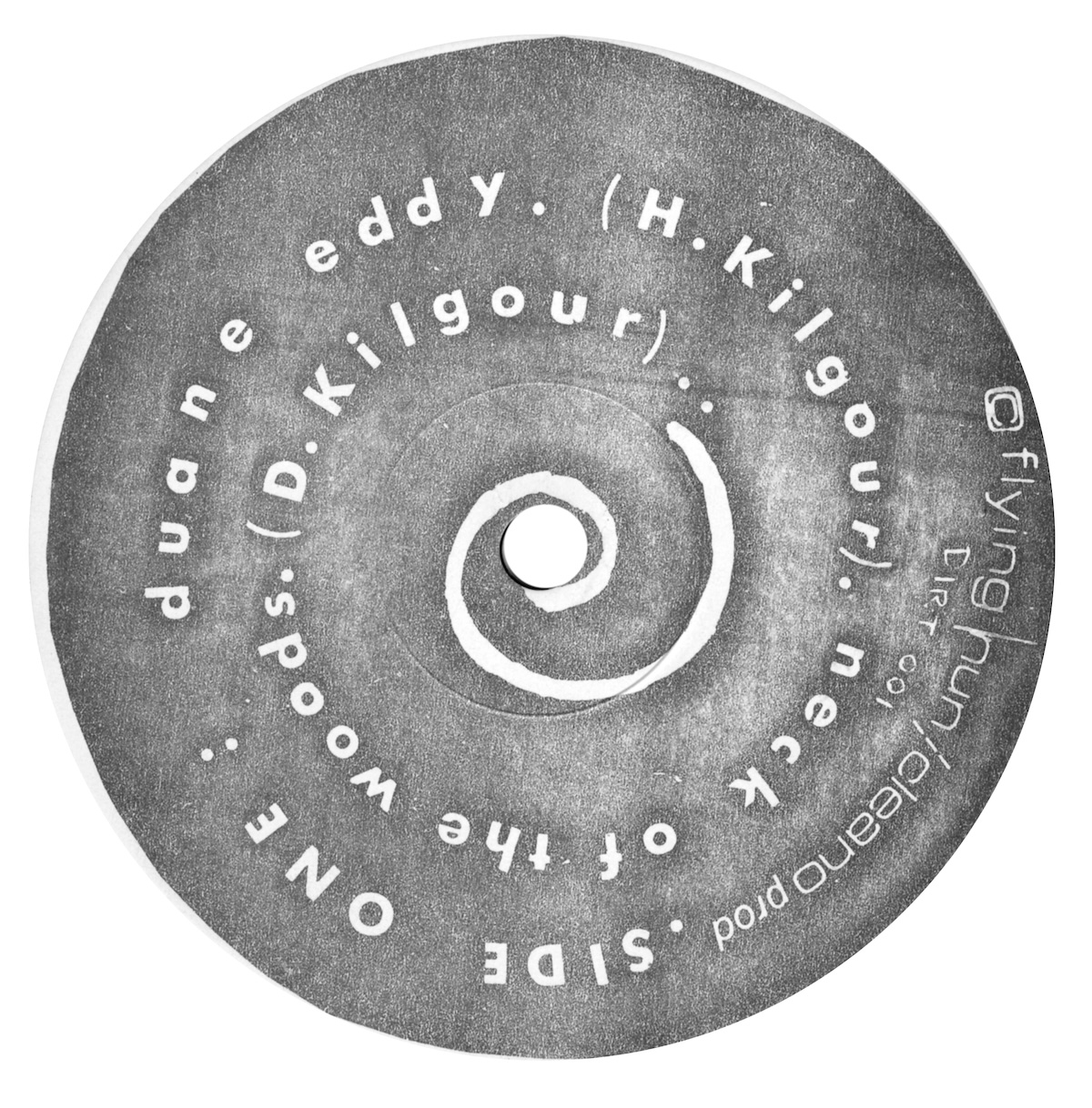

Singles

EP, 1984 (DIRT001)

A Timeless Peace

EP, 1984 (FN023)

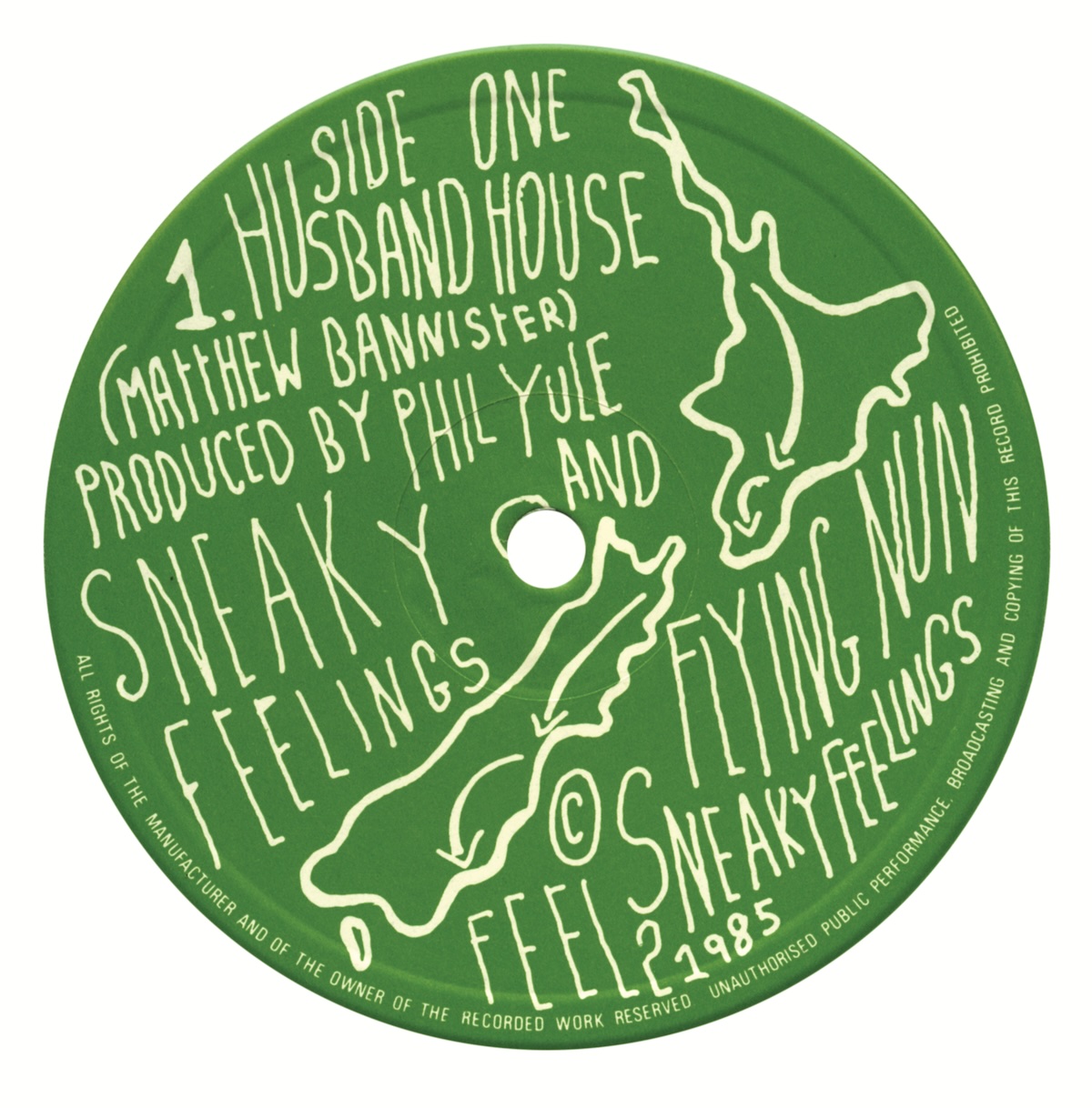

Husband House

12", 1985 (FEEL2)

The Grotesque Singers

EP, 1985 (FN033)

Cut It Out

EP, 1985 (DH002)

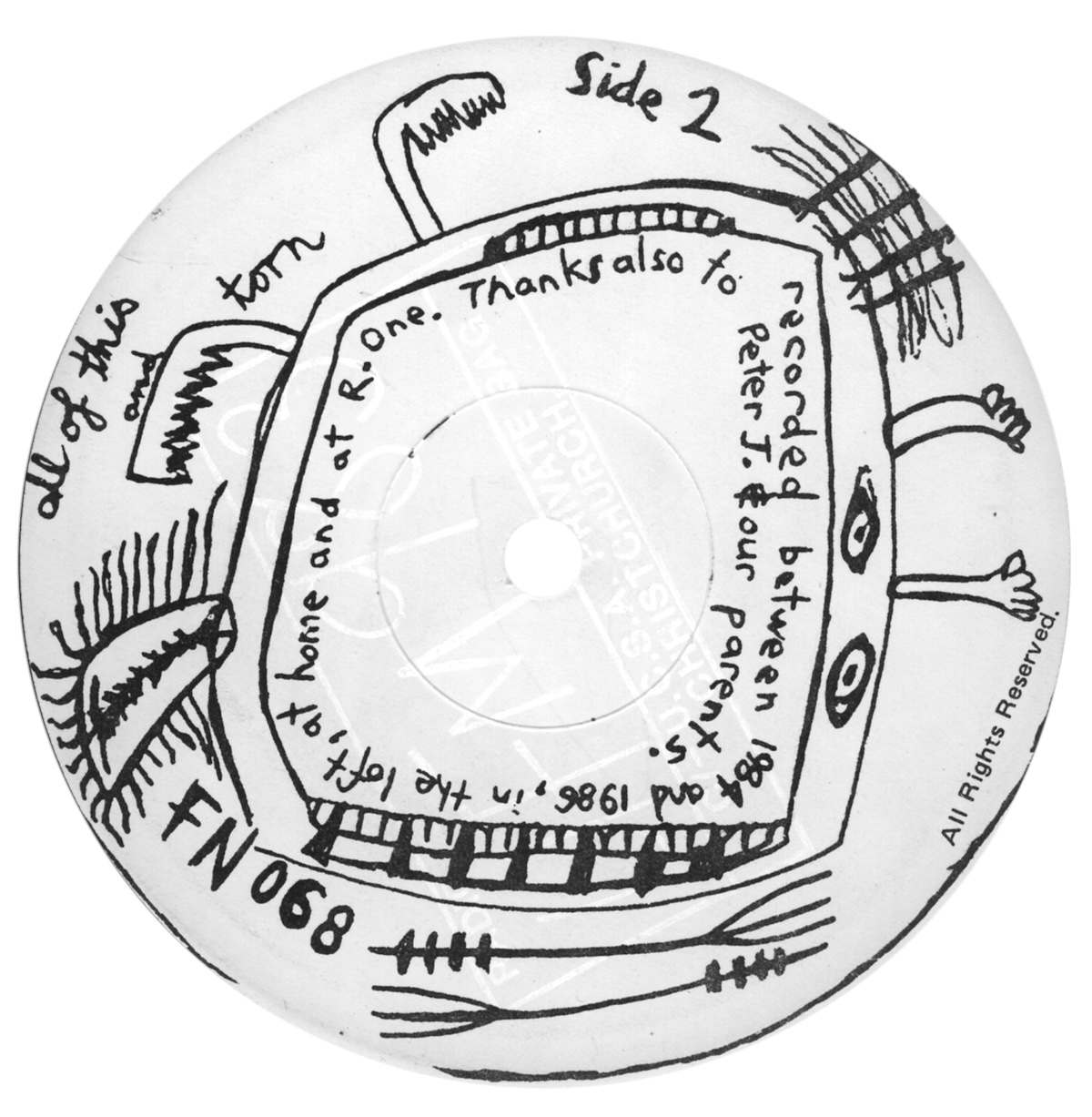

River Falling Love

EP, 1986 (FN0068)