Typo: Introductory – Luke Wood

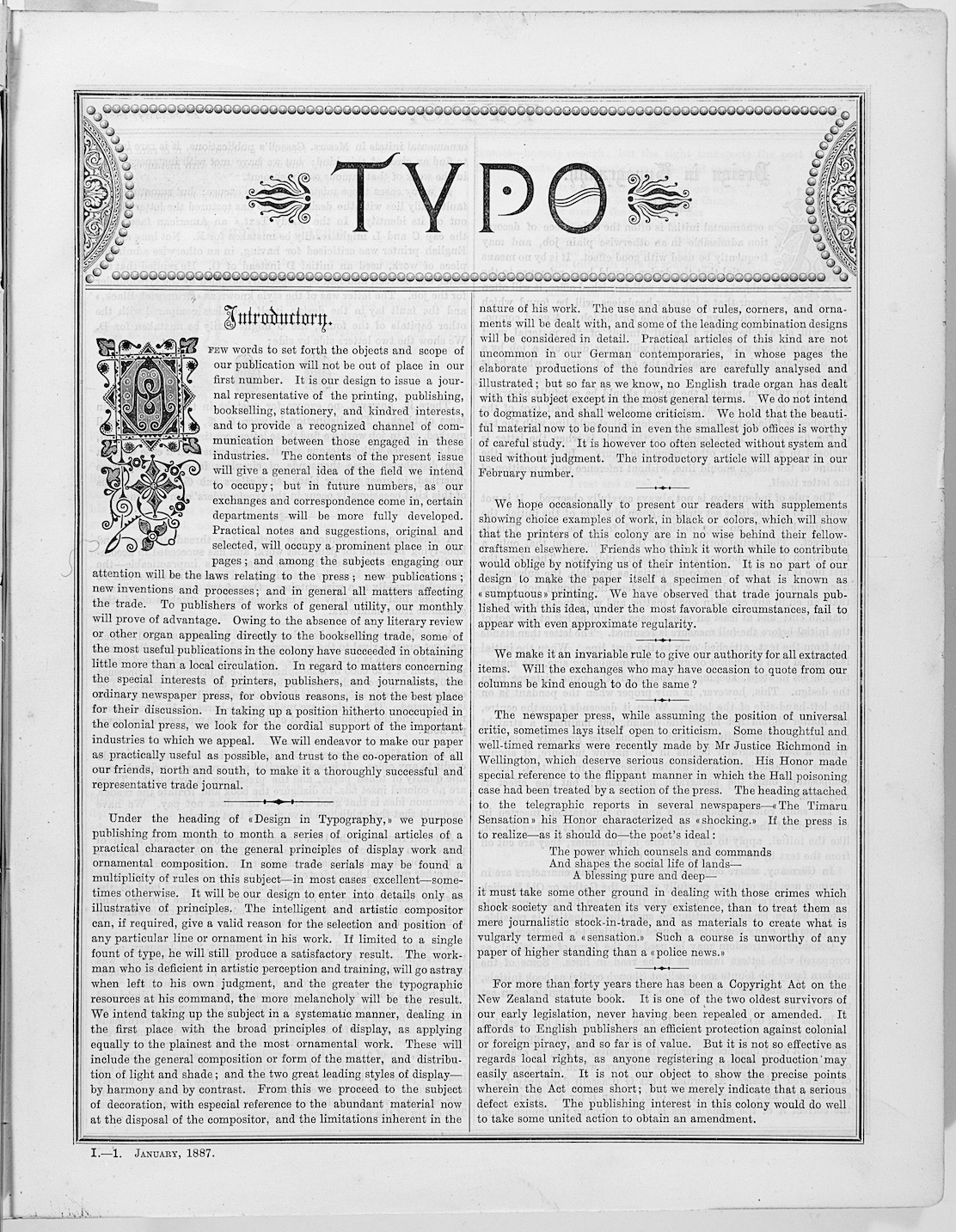

I was first introduced to Typo by Noel Waite about four or five years ago when I was in Dunedin installing an exhibition at the Hocken Library. I’d never heard of it before, or of its author, editor, printer and publisher—Robert Coupland Harding. During a break from setting things up in the gallery I was able to take a brief look at the copies available in the Hocken Library’s collection, but was unable to engage with it in any sort of meaningful way in such a short amount of time. It needed to be read, obviously. I left Dunedin with a vague idea I’d be back again sometime soon with, somehow, more time on my hands. But it hasn’t been until quite recently that I’ve been motivated to actually pack my bags and head to Dunedin with the particular intention to begin to get to know this publication, and something of the man who produced it.

Setting out, I’m interested in Harding as a Typographer who, disenchanted with the industry at hand, attempted to improve his situation through self-motivated critical writing and independent publishing. My own immediate engagement with this publication then, is not so much to do with its Victorian aesthetic, but rather with the ‘spirit’ of its author, and the strategies and tactics employed in its production and distribution.1 And so naively perhaps, but with the best intentions, I’ve come to Harding’s publication looking for a precedent for The National Grid, wanting to know more about Typo’s successes and failures within the framework of a particular national context (that is, in some respects, still very similar today).

More generally, and sort of off-to-the-side a bit, a broader question has emerged about New Zealand’s design history—particularly ‘graphic’ design history, and its relative availability to practitioners. In an article Noel Waite wrote for our first issue he outlined a desire for a “functional design history that establishes local precedents and encourages designers to knowingly develop or subvert them.”2 Writing to Noel recently I complained that so much of this sort of knowledge seemed to exist only within a tight-knit community of academic bibliographical historians, and didn’t seem to make the journey over/across into the surely-somehow- related area of contemporary graphic design practice. To which Noel replied: “It’s not that it’s hidden away in academic journals, rather, like Typo, it’s still sitting in the museums, archives, private collections and people’s heads. Designers AND academics need to get amongst it.”

The ‘article’ that follows—selected reproductions3 of Robert Coupland Harding’s publication used to illustrate a brief biography written by the late Don McKenzie—probably does little to answer the explicit challenge laid down by Noel. It has though, for me at least, worked as an intro- duction to certain ways and means by which, as a designer, I might begin to engage with a local precedent that is, more often than not, hard to find, let alone “develop or subvert”. It is my intention that these reproductions —to be both ‘looked at’ and read—should act as a beginning, a sort of ‘part 1’ of an ongoing project that can be played out in various ways (more speculative or poetic perhaps) in future issues of this publication.

Footnotes

While Robert Coupland Harding is believed to have never left New Zealand, Typo was distributed widely overseas, and particular articles were internationally syndicated via a network of global print trade publications. Here I’m interested in how—whether it was his immediate intention or not—Harding was able to use the publication as a vehicle around which to develop a much broader and more complex community of practice than what was immediately available to him at the time. ↵

NoelWaite, ‘The Lay of the Case: Putting New Zealand Communication Design on the Map’, The National Grid #1, March 2006. ↵

All reproductions of Typo here are from The Hocken Collections, Uare Taoka o Hakena, University of Otago. Thanks especially to Mary Lewis for her assistance with this. ↵